Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

by Dr. Marie Rose Wong

Chinese American History in Context

On 8 May 1882, the 47th United States Congress passed Chinese Exclusion Law in what would be the first significant piece of federal immigration legislation and the only such law that was based solely on race. During its enforcement, the law had seen several revisions and additions with each one being more restrictive in determining which Chinese immigrants would be allowed to enter the United States. Chinese laborers were prohibited from entry beginning in 1882 and wives of laborers and merchants were forbidden entry in 1894 and 1926, respectively. Those Chinese immigrants who were allowed entrance fell into the narrow categories of merchants, teachers, scholars, and diplomats; with each of these immigrants facing a litany of detention and interrogation questions before being allowed entry. Viewed as a perpetual foreigner, Exclusion Law reinforced previous laws that prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens. This immigration law forged a demographic profile of Chinese America that included few women and children with a delay of the birth of a second generation of Chinese Americans for over two generations.i

Exclusion laws dragged on for sixty-one years until WWII when China and Chinese Americans were viewed favorably as joining in America’s fight for world freedom and democracy. By the time America had entered this war, China and Chinese Americans had already been engaged in the fight for over ten years. China’s internal political battle between Chinese Nationalists and Communists had combined with a simultaneous and undeclared war against Japan’s insurrection, occupation, and brutality that began in Manchuria in September 1931 and that had spread to conquering and devastating Shanghai in less than six months. It was America’s entrance in the war that finally generated national political sympathies for what the Chinese people in the US and abroad had been addressing for years. China and Chinese Americans were viewed as loyal allies against a common enemy and rewarded with the repeal of Chinese Exclusion Law. Immigration was now possible but with quotas that were kept at 105 persons per year. For the first time, naturalization of immigrant Chinese was allowed but the allegiance to the country of that citizenship came under scrutiny with political events of the 1950s.

Wary suspicions of Chinese Americans rose with questions of national loyalty and new avenues for discrimination found impetus that were fueled from the Communist Revolution and formation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on mainland China in October 1949. The beginning of the 1950s entrance into Cold War politics and the era of McCarthyism began in earnest. America’s joining the Korean Conflict in July 1950 served to exacerbate the briefly dormant discrimination against Asian Americans with questions about the identity of Chinese American loyalty and where their national sympathies would lie in the rising fear of Communism.

During its tenure, exclusion law, immigration quotas, and the 1940s and 1950s political and popular images of Chinese Americans dictated and shaped the demography, profile, and acceptance of the ethnic social community that in turn formed the physical environment and settlement that was known as Chinatown in American cities.

Intersecting Interests: Democracy on Display and the Expanded Role of Chinese American Women

As diplomacy between America and Communist China waned with the planned closure of consulate offices and embassies on the Chinese mainland, and with economic sanctions, Chinese Americans also experienced the emotional strain.ii In part, focusing on and exhibiting loyalty to the US came from engaging in cultural activities that were seen by the greater public and by forging ahead with revising traditions that would help provide political distance between the image of the Chinese in America and Chinese Communists.

Chinese New Year activities that had a rooted American tradition of being celebrations for the community of primarily single men within the confines of Chinatown were launching into a broader opportunity for public relations with the greater community. Chinese American participation seen in a broader venue of festivals and parades was a means of showcasing the ethnic community as a part of America’s democratic ideals.

In 1950, the small Chinese New Year lion dance celebrations from Seattle’s 1860s that had centered on community grew to become part of the city’s International Carnival neighborhood fair, joining the city-wide festivities of the newly formed Seafair summer festival event. Seattle’s Chinese American community participated with two parades; providing one for the neighborhood and one that would participate in the downtown parade.iii In 1951 and under Seattle Mayor William Devin, reference to the “Chinatown” neighborhood was changed to the “International Center.” Devin’s administration had political goals of acknowledging other cultural groups that had settled in that neighborhood and as an effort to help stem anti-Asian prejudice. It also enabled the city the opportunity to promote and reap the economic potential that tourism in a multi-cultural community would bring.

After a ninety-year presence in the city, the 1950 population of Seattle’s Chinese American community was still at a modest 2,650 with a gender ratio of 1.9 males to 1.0 females that had made scant improvement from that of the 1940 Census. What was occurring was a stronger presence of Chinese American girls whose lives intersected the institutions of Chinatown with school and family responsibilities.

The opportunity for Chinese American women to be seen outside the home environment had improved during the war years with their engagement in factory, industrial, clerical, and food-producing jobs, many of which were associated with national defense. After the war, many of these jobs were vacated and assumed by returning veterans. With marginal employment avenues in the greater community, gender, and cultural role expectations of the 1950s, and limitations within the Chinese American community, Chinese American girls and young women had few opportunities for extracurricular or social activities.iv

There were [so few options] for social events for girls. It is such a huge contrast of what was available then for young people community-wise when compared to today. The boys had the dragon and lion dances…they had scouts, so the male members of the community had options for activities, but Chinese American girls really had nothing.

– Bettie Luke

There was nothing for the Chinese girls to do. Our family laundry business was in the university district and all of us worked every day after school. [Like me and my sisters], some of the girls lived elsewhere and out of Chinatown so there wasn’t much of an opportunity for us to even see one another or ever get together.

-Ruby Luke

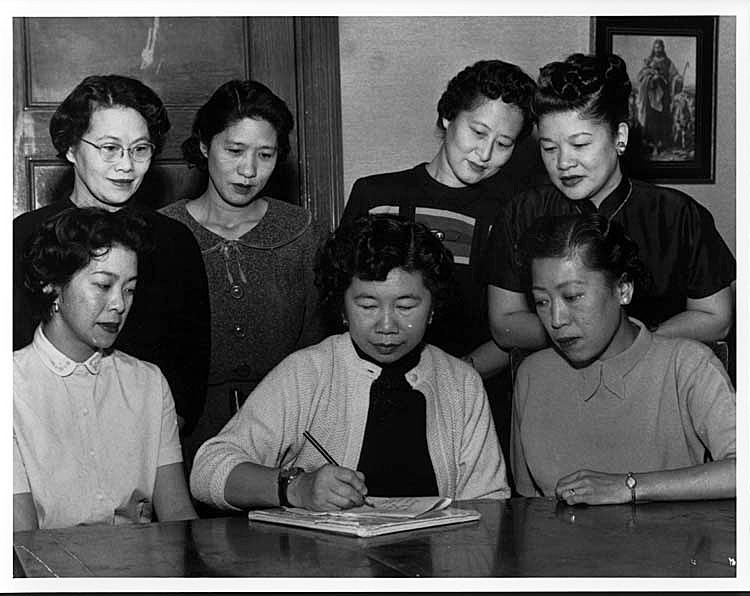

In the fall of 1951, a group of young Chinese American girls who were members of the Chinese Baptist Church began talking about forming their own organization that would unite them regardless of which school they attended or where they lived.v Representing Garfield, Franklin, and Cleveland High Schools, fourteen girls started a club that they called the “Chi-ettes.” As an endearing term, the name combined “Chinese” with the then popular suffix “ette” that referred to a small group of young women. They selected two advisors, Bertha Chinn and Bernadine Wong, to help them organize their membership, and to establish a constitution, goals, and club projects that would fulfill their mission. The first officers of the club were Foon Woo as President, Rose Lew as Vice President, Kay Chin and Sylvia Chun as Secretaries, Sandra Chinn as Treasurer, and Jeanie Jue as Historian in charge of keeping photographs, and memorabilia of the organization’s activities.vi

The Chi-ette’s constitution stated a three-fold purpose that included “stimulat[ing] a closer feeling of unity and companionship among the Chinese girls and to render service to the Chinese community and to join the younger girls of the Chinese community in friendly understanding by working and being together.”vii By the time the constitution was established, the Chi-ettes had grown to 22 members of girls between 15-18 years old. The Chi-ettes also started a chapter for younger sisters who were 12-14 years old and who were interested in eventually becoming “senior” members.

![The Original 14 Members of the First Meeting of the Chi-ettes. [Photo Courtesy of Ruby Luke]](https://frontporch.seattle.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2021/10/Photo-1-Chi-ettes-web.jpg)

The initial club project was to form the first choir for the Chinese Baptist Church, sewing choir robes, and launching the first performance at the 1951 Christmas Eve service. Between Christmas and New Year’s, the Chi-ettes “spent the whole weekend scrubbing the social hall floor of the Chong Wa Benevolent Association for an upcoming community dance, a project that was requested to the Chi-ette’s advisors.”viii

The first social of the club was held on 21 February 1952. Throughout that first year and into 1953, the Chi-ettes held several other social events for Chinese American girls to introduce the organization and its mission to potentially new members. Meetings were conducted using Robert’s Rules of Order, held every month, and rotated to the homes of each of the members with conversations that addressed projects that could be done to help support the community. Finding projects for outreach were sometimes suggested by parents who were active in family or other associations in Chinatown. Each Chi-ette paid organization dues of 25 cents that would then be used to help underwrite costs for printing of fliers and raffle tickets for fundraising projects, such as dances at the Chong Wa or box socials. The Chi-ettes also participated in city-wide events, such as a clothing drive sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee that was taking collections for Korean orphans following America’s involvement in the Korean War, or the annual Christmas-giving campaigns held in Chinatown to raise funds for Seattle’s needy.ix

Transitioning the Chi-ettes to the Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team

Over twenty years before the Asian American Movement began and twelve years before Betty Friedan’s ground-breaking publication of The Feminist Mystique, Seattle’s restauranteur Ruby Chow was already engaged in redefining gender roles and seeking avenues that would empower young Chinese American women. Politically ahead of her time, Chow pursued many avenues of community engagement in Chinatown and seized all opportunities to encourage and nurture the potential of Chinese American youth and particularly Chinese American girls. She envisioned the impact of one such possibility when she was contacted by young Chi-ette president, Foon Woo.

I was sitting in Ruby’s Restaurant float in the Chinatown Night parade in 1951. She knew me because I worked for her doing babysitting. She asked me if I would sit on her float with Ruby’s five-year old daughter, Cheryl. We were at the back of the float and waving at the people on the street. I remember looking at the performers behind us…it was [the] St. Mary’s Girls Drum and Bell Corps from San Francisco’s Chinatown. I thought that our Chinatown could have a drill team of our own like this and so we talked about it at our next Chi-ette meeting.x They didn’t only march, but they had a band of bells and drums.

– Sandra Chow

All of us Chi-ettes thought that having a Chinese girls drill team was a good idea and we voted in favor of it. We wouldn’t have to rely on San Francisco’s St. Mary’s Drill Team or the Chinese Girls Drill Team in Victoria to come to Seattle…we’d have our own. We thought that we needed another advisor for this to happen, so we decided to ask Ruby Chow…she was well-known throughout Chinatown and a leader in the Chong Wa. We elected our chapter president, Foon Woo, to talk with her and pitch the idea of forming a drill team and merging the Chi-ettes. When we did, she really liked the idea.

– Ruby Luke

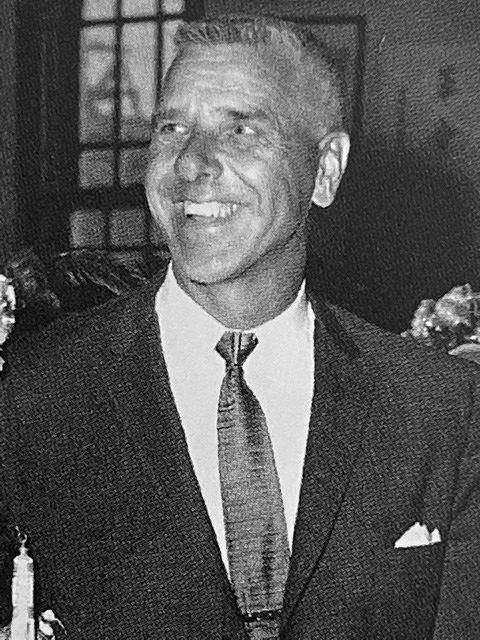

Respectfully and affectionately referred to as “Auntie Ruby,” Chow had an assertive, determined, and dynamic personality.xi Shortly after the idea of a drill team was presented, she attained sponsorship from the Chong Wa Benovolent Association as a means to help with community outreach and support. She also approached Theodore W. “Ted” Yerabek, an officer with the Seattle Police Department (SPD) whose assigned beat was Chinatown.xii

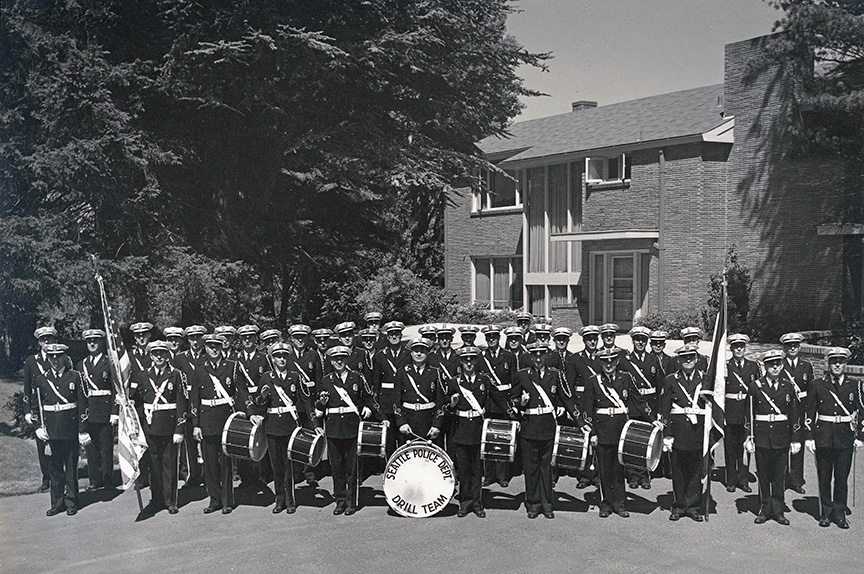

Yerabek was a respected and well-known officer in the Asian American community who was noted city-wide for his commitment to and activities in volunteer service, and since 1949 he had been a member of Seattle’s multi-award-winning Police Drill Team.xiii Officer Yerabek knew Chow when she was a waitress at the Hong Kong Restaurant and became a regular patron when she and husband Ping opened Ruby Chow’s Chinese Dinner Club, Inc. in 1948.xiv It was in this latter setting that Yerabek was approached by Chow and asked to help her organize, train, and teach a group of young Chinese American girls to be a precision performing drill team. The Seattle team wouldn’t be like those in San Francisco or Victoria, B.C. as it would be patterned after the synchronized marching movements with training that was based on military maneuvers and the close-order drills of the SPD. This goal would be the distinctive difference. Chow would act as director, and Yerabek would be their instructor.

Ruby Chow’s visions were built on the Chi-ette’s constitution of community service and were not limited to performance goals of a drill team but expanded to include reinforcing cultural pride and creating connections to improve relationships between Chinese American culture to the greater Seattle community and beyond.

In 1949, she overheard a conversation where Chinese children were playing outside and by her restaurant. [One of the girls was] a fair skinned Chinese and a passerby thought she was white. The passerby told that little girl not to “play with the enemy.” After that, Auntie Ruby talked with the members of the Chong Wa about [Chinatown and] public relations…we needed to have a campaign so that people [would] understand Chinese culture [and] know they had nothing to fear from us. The all-male board gave the go-ahead for it but told her that she would be responsible for doing the work. That’s when she began [looking for ways to] build bridges between Chinatown and the greater community.

-Betty Lau

The more education there was, the more understanding and respect there would be for Chinese American culture.

– Wendee Ong

The SCCGDT was the means to help build that bridge and instill team spirit that would empower each young woman to develop their individual potential. A drill team would teach camaraderie and mutual respect and nurture the idea of equality and the importance of every individual’s contribution to the overall success of the team.

Every person and every assignment in the Drill Team was of equal importance…that [philosophy] was strong in that it broke through any social class restrictions that might otherwise be there. It didn’t matter how much money your parents had or where you lived. Every girl on the Team…drummer, banner girls, lo san carriers, member, captain, lieutenant…every one of us was equally essential to our performance. Auntie Ruby always reminded us of this…. All of the drill team members and alums remember starting out as novice banner girls or lo san carriers who [held] cylindrical-shaped flags at the back of the team.

– Gloria Lung Wakayama

The performances of the newly formed Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team enabled them to serve as ambassadors that connected Chinese Americans to greater Seattle and ultimately outside the state through national and international engagements. Chow and Yerabek were the beginning of a partnership that would prove to be immensely successful in what Chow hoped to accomplish for “her girls” and in what would result in the organization’s legacy, decades of life-long friendships, and numerous award-winning performances.

In the early years and by ordinance, performing at any public venue in Seattle required that a participant had to be at least 12 years of age, which became the threshold requirement of any girl wanting to join the drill team. Allowing this younger age to be on the Drill Team also opened the possibility for those members who were still in the Chi-ette “ little sister” chapter organization to be admitted into the SCCGDT.

The Chi-ettes had a capped membership of 25 and we had 22 members at the time. Ted Yerabek told us that to put a drill team together, we’d have to have 30-50 members because we’d need 32 marchers in eight sets of four along with drummers, banner carriers, two lieutenants, and a captain who direct the team during performances. We had to put together fund-raisers to get out the word to increase our membership. The activities of the Chi-ettes expanded to include dances and socials that were to help raise awareness and get people interested so that they would want to be involved in joining our drill team. Our families wanted to be sure that we would be safe and protected and Auntie Ruby guaranteed this. The rules were clear…stand up straight and proud,” “no boys allowed,” “stand up for each other.”

– Ruby Luke

While we worked on increasing membership, Ruby’s focus was getting financial support and the uniforms. The Chong Wa group helped contribute some of the money that was needed. Auntie Ruby even took a small group of us girls into some of the gambling joints in Chinatown to ask for donations for the drill team uniforms. No one could or would turn down her request because it was for the good of the community.

– Sandra Chow

This seed money would be used to purchase that first set of uniforms in a rich, colorful red and gold design of silk and satin fabric. Chow enlisted her husband, Ping, to instruct the carefully executed design.

Uncle Ping’s expertise and experience as a Chinese opera performer instructed the design of the uniforms that reflected women warriors in traditional operas. He had the outfits made in such a way that their [design and construction] would fit anyone [regardless of height or weight]. [Like those used for opera performers], one size would fit any girl.

-Bettie Luke

In 1952, the Drill Team uniforms consisted of 11 pieces with an elaborate head dress adorned with sequins, tassels, and glass beaded jewels.xv The skill of wearing the costume was in knowing the order in which each piece would need to be assembled. There was no charge for the uniform and no fee for being a member of the Drill Team. The only requirement was for a member to have a pair of white shoes. Even this was negotiable and paid by the organization whenever it was needed. “One thing about Auntie Ruby was that she made sure that girls who wanted to join, were able to join.”xvi No girl would be turned away for the cost of a pair of shoes. That first order of 40 uniforms was placed in Hong Kong at a cost of $40 each.xvii

Uncle Ping and Auntie Ruby personally picked up the uniforms in Hong Kong. When they got there, they were met by Uncle Ping’s nephew, Heyward. He was going to join them on their return, and it was his first time coming to the US…he was 18 years old and spoke no English. They told him not to pack anything, so he only brought a toothbrush in his pocket and one suitcase that was filled with uniform headdresses.xviii

-Sandra Chow

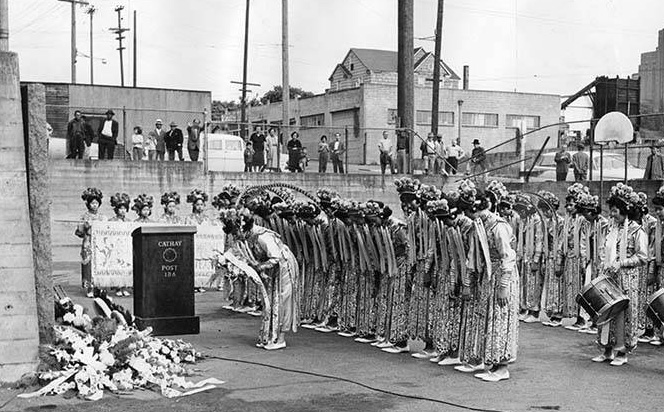

By mid-1952, members of the Chi-ettes had transitioned to become the Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team (SCCGDT).xix They had reached the desired number of participants and began training in the same marching and disciplined maneuvers that were taught to military and police drill teams.xx The most impressive drill that served as the finale of their performance was the St. Andrew’s Cross that was done with marchers lined in an “X- shape” of a diagonal cross and with perfect alignment of the 4 lines.

“Ted Yerabek thought this was a very good drill for us to know and Ruby added the gin-lai or the bow at the end of the drill. Often done in a single bow, we’d do this at the review stand.”xxi Dress rehearsals took place on 7th Avenue South in front of the Chong Wa Benevolent Association with practice sessions every Saturday morning from March to August, the peak period of performance engagements.

In their first year, there were 32 girls that were divided into two teams that each consisted of four squads of four members. Using the same leadership structure of the Seattle Police Department Drill Team as a prototype, Yerabek assigned positions for a Captain (Fannie Wong), First Lieutenant (Barbara Mar), and 2nd Lieutenant (Alyce Eng). Drills would be called out by the team captain and executed by lieutenants and their teams. It was the responsibility of each member to know the marching routines when called out by number. Debuting their first performance in the summer 1952, the SCCGDT began competing in 1953 and won four performance awards that year, which included the Seattle Seafair Grand Parade.

One event that is really memorable to me was that very first time we performed at Seafair. The crowd went wild and it was such a rousing experience. Yerabek was so strict but also a very nice man. We were well-trained and we knew this when we went into our performance…it gave us confidence.

-Ruby Luke

As the younger sisters of Chi-ettes [my sisters and I got to see] the Drill Team give performances…we saw what they were doing and accomplishing, and it had a tremendous effect on our wanting to join. My sister Marge was 13 and I was 12 when we both joined the team. The Drill Team built relationships and helped [to provide] a bond for our generation of girls. It became a tradition…and Ted Yerabek was still there. The year that I was on the Drill Team, we were featured on a television program called “You Ask For It.”

-Bettie Luke

The number of invitations and competitions continued to multiply with travel to local and regional events that ultimately branched out to include requests for national performances.

The brothers, uncles, and fathers of the girls along with community volunteers provided help with the transportation that was needed for us to go to our planned events…it was particularly important as we got calls to do more engagements for performing farther out of Seattle. At one time we even had our own bus for travelling.xxii There was so much community exchange [and connection] within the Chinese American communities. I remember when we were on our way to perform in the Portland Rose Parade. An arrangement [had been] made with a Chinese Restaurant between here and Portland for us to perform and we got our dinner free. When we got to Portland, they arranged for us to stay at the YWCA and held a dance for us. School basketball players and performers for the lion and dragon dance were there.

-Bettie Luke

We went to San Francisco to perform at the Chinese New Year Parade in February. It took us two days to get there by bus. The bus rides were so much fun. We’d ride for 8 hours and sing songs along the way. Auntie Ruby would make these bologna sandwiches with butter on Wonder Bread for these trips…I don’t know if it was good for us but it didn’t kill us because we’re all still here. She donated everything that we would need [for these trips]…she had a heart of gold and was so protective of all of us. We stayed overnight in Grants Pass and slept in a gymnasium in sleeping bags. She knew the restaurant people there and they’d feed us. Then we got to San Francisco and slept on another gymnasium floor. I remember the day of the parade. It rained and our bright red costumes were covered by clear rain jackets but before we got to the reviewing stand [and in a brief break in the parade performance], we took off our raincoats and gave them to the chaperones walking beside us. The chaperones were volunteers who helped with the Drill Team, many of whom were Drill Team alums or parents.

-Wendee Ong

Because practices were on Saturdays and my parents were busy working, Auntie Ruby arranged carpools for those of us who needed rides, bus rides [were] too long or non-existent since practices were 8 a.m. to noon. My carpool dad was Consul General Lu, the first ROC Consul General appointed to Seattle in the mid ‘50s.

-Betty Lau

In 1955 as the reputation of the Drill Team was growing on the West Coast, Life Magazine published a photograph of the Team and dragon from one of their performances. But the journal’s issue was focusing on a theme of “Religion in the Land of Confucius” as part of their World Religion series. While the photo caption brought notice to the Team, the accompanying article entitled “Communists and Confucius” had noted only a tangential cultural connection at best. It failed to address the differences between Chinese from China and Chinese Americans and, most significantly, it did not take note of the accomplishments that were being made by Ruby Chow and Yerabek’s dedication to building the Drill Team and empowering Seattle’s Chinese American women.xxiii

The network of recruiting girls for the team included outreach that was made possible through key organizations of the community, organizations that had been part of the foundation of Chinatown’s history.

As a child, my grandfather [would] take me to sit on the front steps of Chong Wa to watch the drill team practice. We knew it was practice time because we could hear the drums all up and down King Street. I was impressed by the bright red uniforms, the headdresses, the precision of the maneuvers. After a few minutes, Gramps would turn and say to me, “Someday you will be in that group, and you will be just like them! How would you like that?” I always said, “No, no. I can’t,” thinking they were too grand for me. And then he would laugh, as though he knew something I didn’t.

-Betty Lau

Many of us in my generation of Chinese knew each other from Chinese School, [the] Chinese Baptist Church, or from being dragged around by our parents to family association picnics, [and other] events. One Sunday after [the] Chinese Baptist [church] had let out, it was quite noisy. Aunty Alma spotted me trying to go out the doors and asked how old I was. [I was] 12. Because it was so noisy, I thought she was asking me to help at a church dinner. I said “yes,” but I [must] tell my parents. They [agreed and] dropped me off at the dinner, but to my surprise, I was a guest, not a server! It was a [Drill Team] recruiting dinner full of Chinese girls about my age. I decided to join.

In the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair Century of Progress, both the Seattle Police Drill Team and the SCCGDT were headlining performances. In 1980, the SCCGDT performed a drill on stage and before the musical production of “Annie” at the grand reopening celebration for the newly restored and historically designated Seattle 5th Avenue Theatre. Through the coming years, some of the other most notable performances of the Drill Team included the Portland Rose Parade, San Francisco Chinese New Year parade, Disneyland parade, Omak Stampede, and the 4th of July parades in Philadelphia and Washington DC.xxiv

Performance at the annual Seafair Parade was a standard event. At home in Seattle, the SCCGDT performed before visiting dignitaries that included Presidential Candidate John F. Kennedy (6 September 1960), the Vice President and Premier of the Republic of China, C.K. Yen (19 May 1967), and Vice President Richard M. Nixon’s campaign rally that took place in Seattle’s downtown University Plaza (25 September 1968). In early 1972, the SCCGDT made their first international appearance when they were invited to perform in Taipei at the May 20 inauguration event of President Chiang Kai-shek.xxv

We got invited because Auntie Ruby knew Chiang Kai-sheks. As a result she knew all the ministers of the cabinet. She hosted events when they came to Seattle. It was double 10, October 10th Independence Day [and] she arrange[d] for double 10 and the Chong Wa ceremonies. She knew the minister of foreign affairs and he said they were going to bring over a lot of overseas Chinese. She asked him, “Why don’t you invite the Drill Team?” So that’s how she got the invitation.

-Betty Lau

I was 11 years old…and I went on a plane out of the country for the first time in my life; [having gotten] my shots and with a passport [in hand]. I was with the team and had never been on an airplane. Every 5 or 6 girls had an adult as chaperone. Four 11-year-olds in a hotel room having a great time away from home!

-Sue-May Eng

Chow secured air fare as a donation from Eva Airlines for the group of 60 drill team members, accompanying 10 chaperones, and delegates of the Chong Wa and Chinese Parents Service Organization.

The first time we went to Taipei, Auntie Ruby called in some of the alumni who were 21 and 22 years old and brought them back for a larger drill team performance. Auntie Cheryl was directing Drill Team but for this performance, Auntie Ruby came back…and she checked everything.

-Sue-May Eng

I remember meeting President and Mrs. Chiang Kai-shek and going to the palace. I got called to volunteer for the performance…I was 22 at the time so was an alum marcher. The cost of the trip was $200 and that included all expenses…we stayed at the Mandarin Hotel for 2 weeks. President Chiang Kai-shek was 86 and very frail and there were two men who accompanied him on either side as he walked anywhere. For two weeks we performed at different events as there were celebrations [taking place] all over the city. Seven of us wanted to take a side trip to Hong Kong…my dad had some cousins there. Auntie Ruby and Uncle Ping had connections there as well…they knew so many actors and performers, so they arranged to have people take us around the city to see things. One day we were walking down the street and saw Bruce Lee. He had stayed with the Chows for one year, so he and Cheryl knew one another well.

-Wendee Ong

A second invitation to return to Taiwan to perform came for the 20 May 1978 inauguration of President Chiang Ching-kuo. It included both stadium and grand parade performances.

I went on both trips to Taiwan. On the second trip I was a freshman at the University of Washington. A lot of us had been taking Mandarin language at the university so we had a better idea of what was happening [than on that first trip].

-Sue-May Eng

I went to Taiwan with the Drill Team on their second trip, and we did the grand parade [that] went around the city. I was a Chinese major at the U and had taught in Taiwan for a year. All the media wanted to know about us. Cheryl pulled me off the parade route so that I could talk to the television and radio people. They asked general questions like “What do you think of Taiwan?” Where have you been so far? Where do you want to go while you’re here? How many of you are there?

-Betty Lau

During hot weather, parade chaperones would bring spray bottles of water to spritz on the girls faces to help keep them cool during the summer hot weather performances. The weight of the uniforms and the tight fit of the headdress with elastic around the back of the head caused a few girls to faint [en route].

-Gloria Lung Wakayama

During his time with the team, Yerabek ultimately earned the honorific of being called “Uncle Ted” by team members. In 1963, Yerabek donated his annual vacation time to volunteer as the bus driver to take the team to perform in the San Francisco Chinese New Year parade. On their return to Seattle and at the close of Seattle’s Chinese New Year’s festivities on 28 January, Yerabek was awarded a signed scroll that noted his outstanding service to the Chinese American community and his work with the Drill Team. Sponsored by the Chinese Community Service Organization (CCSO) the award was presented at a reception at the Chong Wa by Seattle City Councilman Wing Luke and Ben Woo, President of CCSO.

In 1964, Uncle Ted was honored through a surprise birthday party by team members and the Chows at the Chong Wa. “He was led to a throne on stage and…presented [with] gifts, all handmade by each girl on the team. A banner in the hall declared ‘Happy Birthday Uncle Ted from your Girls: Confucius Say Honorable Yerabek all the Way.’xxvi

One of Ted’s expressions was “Dress it up…Dress right.”xxvii He made a big deal about us always being in a straight line. He was really so incredible…just think, how many fathers would give up their Saturdays with their family to spend it teaching other people’s daughters?

-Betty Lau

[Ted] was such a fine man and so dedicated to teaching us girls. He helped turn us into responsible women. We learned that everyone needed to pitch in no matter what their role or job. We were trained to help one another. If we didn’t win at a performance, he would talk to us about what we needed to improve…what could we do better?

-Wendee Ong

In 1965, Ruby Chow was honored in the middle of a Chong Wa Benevolent Association Board of Directors Meeting when representatives from the first Drill Team presented her with a plaque honoring her years of service to the community, the SCCGDT, and the Chong Wa. The plaque was inscribed with some of her most colorful expressions and one most noted directive to the girls before every performance to “Put on some lipstick, RED lipstick.”xxviii Red was for good luck.

Ruby Chow knew how to rise above prejudice, and this was as important to her interaction with the girls as were her more amusing colloquial expressions. Teaching them how to retain personal dignity and a non-violent response to the prejudice that was still faced by Chinese Americans was the armor to protect “her girls” and prepare them for adulthood. Chow had a deep and personal understanding of these obstacles as a Chinese American woman who confronted the glass ceiling of cultural and professional expectations; experiences that she challenged and conquered on multiple occasions.xxix

I remember at one of our early performances when we won the Best Drill Team award, girls from a couple of the other [competing] teams said that the only reason we won was because of our outfits. Auntie Ruby had already given us a perfect answer [if people said things like this]…she told us to just smile sweetly, say “thank you,” and walk away. We didn’t win because of the outfits, we won because we were well trained and coached…we were precise.

-Ruby Luke

For the most part, people were supportive at the marches. But I remember when my daughter was in the Drill Team in 1969. We would assign parents to stand behind the crowds because we would hear name calling and we wanted to help prevent any potential hostilities [if we could]. Just to be a presence there helped. The name calling and harassment was just there, and we endured it. We didn’t know how to stop it…we could only be on guard and we kept marching.

-Betty Luke

Ironically, racism was worse in Seattle than in the small towns where we performed. Some people in the audience would make derogatory comments…we just kept marching.

-Gloria Lung Wakayama

Like her mother, Cheryl Chow was committed to the same goals of nurturing self-confidence and achievement for all the members of the drill team with a dedication to public service. She had participated in many roles of the team as mascot, banner carrier, as a drill team member, and team captain. Ted Yerabek retired as the instructor of the Drill Team in 1967 and Ruby’s daughter Cheryl stepped up to assume that position. Yerabek was the recipient of gratitude by countless members and by the time of his retirement he had trained 242 girls on the team.xxx Cheryl Chow’s work as an educator and principal at Sharples Junior High School (renamed Aki Kurose Middle School), Franklin, and Garfield High Schools, and two elected terms on the Seattle School board placed her in a unique position to introduce the Drill Team to those girls who might have an interest in joining. Under her leadership, the Team continued to win multiple competitions and trophies, filling the room in the Chong Wa that was dedicated to the Drill Team.

Formalizing a supportive organization for the Drill Team occurred in 1971. As a parent of drill team daughters, Art Lum helped to establish the Chinese Parents Service Organization (CPSO), a supportive organization whose goal was to help raise funds for team travel and to help defray expenses, such as the purchase of new uniforms. One of the most successful ventures and one that brought national attention to the Team and the Chinese American community came when the SCCGDT was featured in the April 1980 issue of The Ladies Home Journal.xxxi The write up profiled the development of a cookbook entitled Flavors of China that was first compiled in 1975 and that contained over 200 family-favorite recipes that were submitted by community members to the CPSO as a fund raiser for the drill team. The Journal noted that:

“Flavors of China…is one of a kind…we salute the group that benefits from cookbook sales—the Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team. Well-known in the Northwest and up and down the West Coast, the Girls Drill Team is a frequent participant in parades, festivals, and exhibitions—much in demand for its colorful performances of precision marching…. The Drill Team…consists of some 70 girls…ranging in age from 12-19. The team is the only one of its kind in this country (and possibly the world), and while their schedule is demanding, everyone on the team considers it a privilege and joy…. Drill Team uniforms are breathtakingly beautiful—each is handmade, consisting of nine separate pieces in intricate designs and including over 7,000 beads per uniform.”xxxii

The article included a few sample recipes of the cookbook along with information on how readers could contact the Parent Organization to order a copy for $6.50. The article helped sell hundreds of copies of the cookbook nationwide and brought greater attention to the SCCGDT and the Chinese community of the Pacific Northwest.

In 1974, the spirit of togetherness was formalized as the Drill Team instituted “The Inspiration Award” in memory of Margie Wah, who was one of the drill team captains. It would be awarded annually to a team member who exemplified “caring, commitment, and selflessness.” In 1979, the Drill team established the “Lin Lee Memorial Scholarship Award” for a team senior named in honor and memoriam of team member, Lin Lee.

The Legacy of the Drill Team

As it was in the beginning, no salaries or financial remuneration is given or expected for any of the directors or community volunteers for their work associated with the Drill Team. It is a “labor of love” and a calling that hearkens deep respect and reverence for generations of the Chinese Community.xxxiii

According to an academic study that was conducted of the SCCGDT, it is in its 7th generation of member participants.xxxiv With such a long and rich history, there has been little turnover of the program directors with Cheryl Chow retaining her work with the Drill Team for almost 50 years. Through her professional life as an educator, school board administrator, and Seattle City Councilwoman, she lived by example those values that she learned from her mother and father that in turn were taught to the girls that she mentored through the Drill Team experience. At last count in 2012, 1,069 girls have been members of the Drill Team, with this number currently being updated for the upcoming 70th anniversary.

The Chinese Parent Service Organization continues to be involved in support of the Drill Team. Since launching that first cookbook, there have been 8 editions with another updated version being planned. New drills have been added over the years but those of the Drill Team’s history remain, including St. Andrew’s Cross and the gin-lai. Each member of the team stands ready to perform 55 drills and commands without hesitation.

Uniforms have evolved over the decades and the Drill Team is on its sixth set since those that were retrieved by the Chows in1952. On 30 July 1958, aqua green uniforms were premiered for Seafair and described as a “Ching Dynasty [design] with dragons outlined in fiery red sequins and breathing fireballs [with] loose panels falling from the waist [to] cover pantaloons.” xxxv At Uncle Ping’s suggestion, there was also the addition of pheasant feathers to the headdresses to be worn to help distinguish the officers of the team. In July 1962 the aqua uniforms were retired, partly due to the loss of brilliance in color and progressive fading that was already becoming noticeable the year after they were placed into service.xxxvi There was a return to red uniforms with gold trim and the addition of gold satin with red trim that would be worn by the Drill Team officers. In 1973, new red uniforms had the addition of white neck scarves and white gloves. Since 1989, bright red satin with gold sequins adorn the most recent iteration of the eight-pound uniforms.

Hong Kong National Treasure Master Chan Kwok-yuen’s company made at least one set of drill team uniforms. I found an old receipt [written from] him for uniforms which he personally delivered to Seattle to Auntie Ruby and Uncle Ping. He remembers coming to Seattle. What is less clear is which set of uniforms he worked on. He’s about 90 and still sharp but not so clear about which set of uniforms he designed and made. He says his company didn’t do the earlier ones as his business was still young at that time…. All the other companies that might have produced sets of Drill Team uniforms are no longer in business.xxxvii

-Betty Lau

The headdresses aren’t heavy but because you have to snap your head [during the drills] when you turn, they have to fit tightly so that they don’t come off. There’s elastic in the back that fits under the hair…and the way that the hair is pulled back into a bun helps keep it in place. The headdresses aren’t pinned…they’re like a headband and they’re tight. We sometimes use foam on the ridge of the piece and that helps. You’re not supposed to touch the headdress if it begins to fall…you just let it go. The girls are like soldiers in that they don’t move out of step. If the headdress falls, one of the chaperones will hopefully pick it up and put it back into place between the drills.

-Lorena Eng

Today, as before, the Drill Team practices on the playground east of the Chong Wa Benevolent Association with meetings on Saturday mornings and additional practice sessions on Wednesday. The current lead staff of the Drill Team are Director/Historian Isabelle Gonn, Instructor Sue-May Eng, and Uniform Manager Lorena Eng.xxxviii Each woman has deep roots to their heritage and the Seattle Chinese American community and are themselves alumni marchers with daughters and granddaughters who have carried on the tradition. Like their predecessors, each woman carries on the practice of community support and heritage identity with pride, a commitment to enrich the lives of each of the Drill Team girls through mentoring and support, and a belief in the value of each person’s individual contribution to the whole of teamwork. They believe in their work and nurturing the relationships that have created numerous lifetime friendships and a cultural understanding with communities outside of the Chinatown-International District. There is a deep appreciation and reverence for the legacy that the Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team has created over time and that is now entrusted to the care of the current team staff and that of the alumni.

The memorable expression that I heard many times from both Auntie Ruby and Cheryl is “without the banners the marchers cannot go out, and without the marchers the drummers cannot go out, and without the drummers the officers cannot go out–everyone is an important and necessary part of the team.” I remember hearing this when I first joined, and it made me feel important as a banner girl!

-Lorena Eng

I’ve been volunteering for 27 years; start[ing] as a team volunteer, [then] team coordinator [from]1997 to 2015 when I was voted in as Director. For me, it was the passion and dedication of [Ruby and Cheryl Chow that is so memorable]. [They]…wanted to teach us to be leaders and that there was nothing that we could not achieve. Breaking through that glass ceiling and stereotype of being an Asian/Chinese -Woman or Man. I will forever be grateful for all the lessons that I learned from both of them. They paved the way to make it better for all of us in our community.

-Isabelle Gonn

Cheryl taught us that the cardinal sin is hurting the feelings of another drill team girl. You’re not just a drill team sister at Drill Team…you stick up for one another no matter where you are. We had a connection to Auntie Ruby and Auntie Cheryl. I know that when people get together, things just “click.” You can’t really explain the pride, the connection of these first childhood experiences. It’s important…I want the new girls to feel it.

-Sue-May Eng

…the drill team is the hostess of the Chinatown Night parade…. Besides leading the parade, the part that moves me [the] most is [at] the end of the parade, when the team stands at ease on Weller Street alongside Chong Wa [as they wait] for other team[s to] salute to each other. It’s spine tingling to watch our team bow to the other drill teams and in turn, the other teams salute ours. It’s a recognition that…we are all part of representing our communities in public. [It is] a recognition of hundreds of hours of practice for just this moment of affirmation of identity and the display of respect toward other like-minded teams…. Sue-May carries on the tradition of a quick parade route stop to signal the captain [that] the team needs to perform a [single] gin-lai (bow) to certain honored elders for their decades of community service….

-Betty Lau

Two weeks ago [in July 2021] with the reopening of Chinatown [since pandemic closures], Sue-May got the Drill Team alumni together and we got to be part of the performance. It took a while [to remember], but the drills came back to us as we were part of the marchers…afterwards we alums all went out to lunch. We may not have seen each other in a long time but we all felt that we went back to our days as Drill Team marchers; back to the way it was for us then…there was such a feeling of pride and it’s part of our hearts and one that never dies.

-Wendee Ong

The long-term lesson of the Drill Team is its legacy…a strong sense of community connection and something that is much bigger than yourself. It taught us all teamwork and equality. Auntie Ruby reminded us that “when you march, you represent you and your community. Stand tall and proud.”

-Gloria Lung Wakayama

The challenges to the Drill Team have changed from those early years. Opportunities for after-school athletic activities for girls did not exist in the mid-1950s. Today, girls have numerous choices outside of being a member on the Drill Team but being part of and building on the tradition of the SCCGDT still attracts new members. Meetings and communicating with the team members about practice sessions are occurring online due to the pandemic that prevents in-person practice. Even so, outreach to every member of the team and doing whatever job needs to be done has continued in earnest.

City municipal budgeting has affected the type of trophies, as they have gone from metal to plastic to plaques to certificates. With the countless awards that the SCCGDT has earned, the alums and members understand that the most meaningful award is in the Chinese American heritage that is at the heart of every performance. With every step, their marching reflects the visions of Ruby and Ping Chow and Officer Ted Yerabek. Every performance represents the faces and traditions of Seattle’s Chinese American community and that of the Seattle Police Department Marching Drill Team that ceased in the early 1980s.

The formula for service, camaraderie, and excellence that was forged by the Chi-ettes and Ruby Chow has remained and expanded with each person who has ever been a part of the Drill Team. The intrinsic and deeply felt value of marching for the common good has withstood the test of time as the Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team approaches its seventy-year anniversary celebration in 2022.

Dr. Marie Rose Wong is Professor Emerita with the Institute of Public Service at Seattle University. Marie has several publications on Asian American settlements and urban development that include Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon (2004, 2012) and Building Tradition: Pan-Asian Seattle and Life in the Residential Hotels (2018). Dr. Wong is board president of the Kong Yick Investment Company, one of the longest-standing corporations in Washington State, and serves on the board of InterIm, a community development association that focuses on affordable housing, social justice, and sustainability in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District.

Footnotes

[i] A generation is defined here as twenty-five years. According to the US Census, the ratio of males to females in 1930 was 4:1 that improved to 3:1 by 1940. These numbers reflect total numbers of Chinese males and females in the US and in Seattle with a 4:1 ratio in Washington State. These numbers do not consider the age quartiles that would account for a higher percentage of older males to young females that may not have been of marrying age.

[ii] One of the most severe economic sanctions was by the US Treasury Department in reevoking the “1917 Trading with the Enemy Act” in 1950 that prohibited Chinese Americans from sending money to family members in China.

[iii] The Chinese American community had previously organized a Chinatown and city-wide parade event as part of the festivities of the 1909 Alaska-Yukon Pacific Exposition.

[iv] Limitations within the community included few opportunities to be part of the decision-making body of family and district associations. The role of women in these associations did include their participation in auxiliary units. One such possibility for an outside activity was attendance at Chinese School that was conducted in the Chong Wa Benevolent Association in Chinatown.

[v] The Chinese Baptist Church was also responsible in beginning the first Chinese Girl Scout Troup 75.

[vi] Officers were included in the 22-member club count.

[vii] Constitution of the Chi-ettes, 1951.

[viii] Sandra Chow Interview, 13 July 2021.

[ix] One of the Christmas-giving campaigns was sponsored by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

[x] The San Francisco drill team is also referred to as St. Mary’s All-Girls Drill Team and St. Mary’s School Drill Team & Drum & Bell Corps. It was formed in 1940 by John Yehal Chinn.

[xi] She was also referred to with a different spelling as “Aunty Ruby.” Use of the words “Auntie” and “Uncle” are honorific terms and do not necessarily imply familial relationships.

[xii] Theodore “Ted” Yerabek was born in 1911 and had chosen a lifetime professional and personal path of service that began with his work as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In 1938, he was one of 2,000 applicants who took the civil service examination and scored the highest grade of the 250 who qualified. He joined the Seattle Police Department (SPD) on 9 November 1942 but left the department in 1943 to serve in the Navy as an underwater specialist during WWII. In 1942, Yerabek began to volunteer time to serve as a water safety instructor with the American Red Cross and served on the committee of the Metropolitan YMCA and as chairperson of its aquatic committee. He began a police water-safety course that later became part of the training given to all officers. He also served as the chairman of the Northwest-Area Skin and SCUBA Diving committee that trained people to become diving instructors.

Yerabek returned to the SPD in 1946 and was assigned to the 1st Avenue beat that included the current Chinatown-International District. By the early 1960s, Yerabek’s assignment was serving as one of the SPD Harbor Police. In 1963, Yerabek was one of six police officers that were honored by the Kiwanis Club. The award was for exceptional community service that went far above and beyond the expectations of their positions as police officers. It was the first such award ever given by the Kiwanis. He retired from the SPD on 8 November 1967, the same year that he retired from the SCCGDT.

[xiii] Seattle’s Police Drill Team records indicate that this organization was formed at the turn of the 20th century and likely the first such police drill team in the country. On 18 July1936, the Municipal News stated that “this drill team is the outstanding police drill team organization in the United States, winning first prize consistently at every competition.” Officers who were members of the Drill Team paid their own expenses for equipment and travel associated with performances. From the 1940s the Drill Team consisted of both precision marching and motorcycle officers, many of whom had training and experience with precision marching from military service. Both drill teams performed into the early 1980s when The Drill Teams were discontinued as part of Seattle Police Department budget cuts. Afterwards, a new group was formed by Officer Frank Campson, who established the Seattle Police Honor Guard.

[xiv] The restaurant was located at 1122 Jefferson Street at the Broadway intersection in Seattle’s Central District, noted as the first Chinese restaurant outside of Chinatown.

[xv] Currently, there are 13 pieces of each uniform ensemble with the 1973 addition of neck scarves and gloves.

[xvi] Betty Lau Email Correspondence, 8 August 2021.

[xvii] The Legacy Marches On. Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team: 50th Anniversary, 2002, p. 8.

[xviii] Uncle Ping’s given name was Edward Shui “Ping” Chow

[xix] Records of the Chi-ettes indicate that the organization name and members continued until the end of 1953. Until that time, additional community service projects continued, such as a caroling fund raiser for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Christmas fund, and a clothing and medical relief drive that was sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee for orphans in the aftermath of the Korean War.

[xx] The SCCGDT refer to “maneuvers” as “drills.”

[xxi] Sandra Chow Interview. Gin-lai means “meeting with respect.” Coleman Mar, Ruby Chow’s youngest brother, is credited with suggesting that this be added to the performance.

[xxii] Bettie Luke Interview, 1 July 2021. In November 1961, the Chong Wa hosted a variety show program that was performed by members of the SCCGDT with proceeds that would be used to purchase the 50-passenger bus.

[xxiii] “Religion in the Land of Confucius,” Life Magazine, Vol. 38, No. 14, 4 April 1955, p. 81.

[xxiv] The Philadelphia and Washington DC performances took place in 1983.

[xxv] A side trip during this event was when some members of the Drill Team decided to fly to Hong Kong to take a sight-seeing trip. While in Kowloon, Cheryl Chow and Wendee Wong (Ong) saw a good family friend and former Seattle resident, Bruce Lee. In his pre-film star years, Lee had lived with the Chow’s. [Zolima City Mag, Part 2, https://zolimacitymag.com/young-bruce-lee-the-man-before-the-legend-seattle-kung-fu/ Accessed 3 October 2021].

[xxvi] Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “Chinese Honor Ted Yerabek,” 12 June 1964, p. 10.

[xxvii]“Dress Right” is a command given by squadron leaders to align the members of a company and platoon into a straight line.

[xviii] “Ruby Chow Honored for Drill Team Help,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 16 September 1965, p. 12.

[xiv] Among her many career accomplishments, Ruby Chow was the first Asian American elected to the King County Council in 1973, 1977, and 1981.

[xxx] “Marching Through Time,” Seattle Chinese Community Girls Drill Team – 35th Anniversary, 1952-1987. This number reflects individual members, the majority of which stayed with the Drill Team for multiple years.

[xxxi] John Stevens, “Flavors of China,” The Ladies Home Journal, Vol XCVII, Issue 4, April 1980, p. 69-76.

[xxxii] Ibid., p. 71.

[xxxiii] Sue-May Eng Interview, 14 July 2021.

[xxxiv] Mei-ying Chen, Contemporary Women Warriors: Ethnic, Gender, and Leadership Development Among Chinese American Females. Dissertation. Seattle: University of Washington, 2003.

[xxxv] “New Look,” The Seattle Times, 31 July 1958. Great care was taken in noting that the imported uniforms were not made in Communist China but in Hong Kong.

[xxxvi] “New Chinese Dancing Lion Costumes Please Drill Team,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 27 July 1962, p. 32.

[xxxvii] Chan’s opera headdress company, Chan Yuen Kee, is in Hong Kong. As a former opera performer, Chan turned his professional attention to costume production in 1955 as an apprentice. He is now a master headdress maker for Cantonese opera performers and has been doing so for seventy years.

[xxxviii] Lorena Eng is also the treasurer of the Chinese Parents Service Organization and has been since 2010.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books and Articles:

Brooks, Charlotte. “Numbed with Fear: Chinese Americans and McCarthyism,” PBS: American Experience, 20 December 2019.

Chinese Community Girls Drill Team. Those Happy Years, 1952-1977: 25th Anniversary. Seattle: 1977.

Chinese Community Girls Drill Team. Marching Through Time, 1952-1987: 35th Anniversary. Seattle: 1987.

Chinese Community Girls Drill Team. Through the Years: 1952-1992: 40th Anniversary. Seattle: 1992.

Chinese Community Girls Drill Team. The Legacy Marches On: 50th Anniversary. Seattle: 2002.

Chinese Community Girls Drill Team. Count Off! 1952-2012: 60th Anniversary. Seattle: 2012.

“The Feminist Movement: Where Are All the Asian American Women?” US-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, No 2, 1992, p. 96-111.

Headquarters, Department of the Army. Drills and Ceremonies. Training Circular, 3-21.5. 3 May 2021.

Maeda, Daryl Joji. Rethinking the Asian American Movement. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Wong, Marie Rose. Building Tradition: Pan-Asian Seattle and Life in the Residential Hotels. Seattle: Chin Music Press, 2018.

Yeh, Chiou-Ling. “In the Traditions of China and in the Freedom of America:” The Making of San Francisco’s Chinese New Year Festivals,” American Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 2, 2004, pp 395-420.

Yung, Judy. Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Interviews:

Sandra Chow, (Chi-ette) 13 July 2021.

Betty Lau, (SCCGDT: 1960-65), 6 August 2021.

Bettie Luke, (SCCGDT: 1957-1962), 1 July 2021.

Ruby Luke, (Chi-ette, SCCGDT: 1952-53), 1 July 2021, 7 July 2021.

Wendee Ong, (SCCGDT: 1961-64), 6 August 2021.

Lorena Eng, (SCCGDT: 1967-74), 14 July 2021.

Sue-May Eng, (SCCGDT: 1970-81), 14 July 2021.

Isabelle Gonn, (SCCGDT: 1971-76), 14 July 2021.

Daniel Oliver, City of Seattle, Police Pension System, Email Correspondence, 22 July 2021.

James Ritter, Officer (Retired), Seattle Police Department, 21 July 2021.

Gloria Lung Wakayama, (SCCGDT: 1967-77), 17 June 2021.

Manuscripts:

Chan, Kwok Yuen Zoom Interview Transcript and Translation. Conducted by Mimi Chan and Maya Hayashi, Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience, 14 January 2021.

Seattle Municipal Archives, Comptroller File 219587, 15 December 1952

Seattle Municipal Archives, Comptroller File 25414, 4 November 1965.

Seattle Municipal Archives, Ordinance 76028, 28 May 1947.

Seattle Municipal Archives, Ordinance 81634, 31 December 1952.

Seattle Municipal Archives, Ordinance 85838, 22 January 1957.

Seattle Municipal Archives, Resolution 22762, 29 September 1970.

Newspapers and Journals:

“Cheryl Chow: 1946-2013 – Courageous Educator, Community Leader and Child Advocate Passes On,” The International Examiner, 3 April 2013.

“Flavors of China,” The Ladies Home Journal, Vol. XCVII, Issue 4, Aril 1980.

Milne, Stefan, et al. “Meet the Women Who Fought for Their Place in Seattle Politics,” Seattle Met, December 2019.

Potts, Billy. “Forgotten Hong Kong Icon: Crafting Cantonese Opera Headdresses by Hand,” Zolima City Mag, 4 September 2019. https://zolimacitymag.com/forgotten-hong-kong-icon-crafting-cantonese-opera-headdress-by-hand/ Accessed 20 September 2021.

“Religion in the Land of Confucius,” Life Magazine, Vol. 38, No. 14, 4 April 1955.

“Random Notes,” Seattle Municipal News, V. 26, No, 28, 18 July 1936.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, articles under various titles from 1954-2015.

The Seattle Times, articles under various titles from 1954-2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My sincere appreciation to the following people whose work during a pandemic makes scholarship possible. Rebecca Baker, Program Coordinator, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries; Joseph Bopp, Albert Balch Curator, Special Collections Librarian, Seattle Public Library; Bob Fisher, Collections Manager, Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience; Jeanie Fisher, Reference Archivist and Anne Frantilla, City Archivist, Seattle Municipal Archives; Adam Lyon, Library Associate, Museum of History & Industry; Holly Sturgeon, Manager, Resource Sharing, Lemieux Library, Seattle University.