Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

by Betty Lau

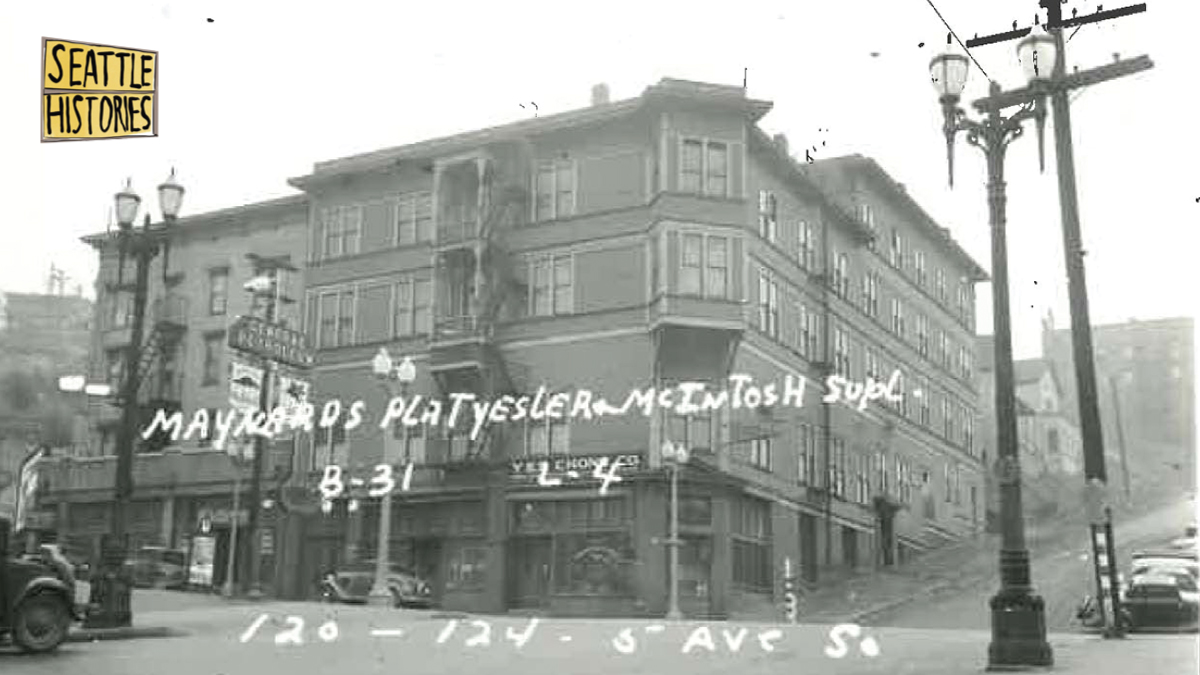

My earliest memories are of living in an old brick and wood building on the northeast corner of 5th Ave. S and S. Washington streets between the second (2nd Avenue) and third (King Street) Chinatowns. Chinese dock and cannery workers had lived on the waterfront, the original Chinatown, where Aunty Ruby Mar Chow was born. Some of my following childhood memories were filled in or recalled by my parents many years later, as well as augmented by reminiscences of siblings, cousins, and relatives who lived with us above our first laundry location.

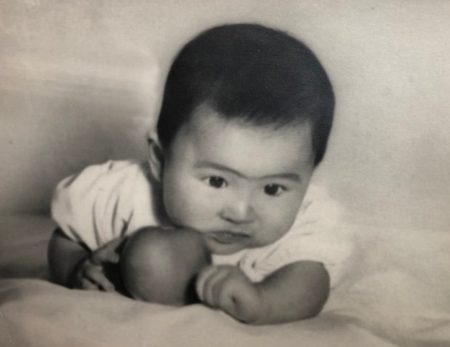

My parents brought me home from Maynard Hospital in the fall of 1947. As the firstborn, the occasion called for official baby pictures. My parents took me to Uncle Yuen and Aunty Mamie Lui’s newly established photography studio, where Uncle Yuen photographed me with an apple.

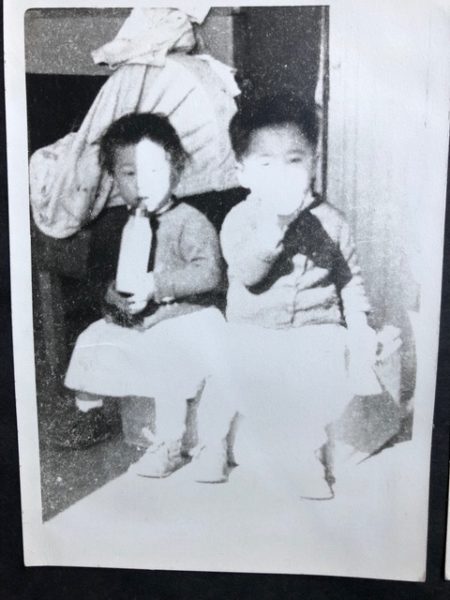

Sister Linda arrived just 13 months later. The next year, mom miscarried. Faced with recovery, childcare for a toddler and an infant, and getting a new business off the ground, she and Dad desperately sought help—they placed us with a seemingly nice farm couple, paying them to care for us, alongside the couple’s own children. Our parents depended on weekly phoned reports and came to visit every two weeks, but after a month, it was clear we suffered neglect: weight loss, unbathed, with Linda still in dirty diapers. We cried upon seeing them. They brought us home the second visit. Dad said the first thing they did was feed us, astonished we devoured an entire loaf of bread and gulped down a quart of milk between us!

They started the first Esquire Laundry with a wedding gift of $500 from Dad’s father and a business loan from the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce branch in Seattle, as American banks declined to do business with them.

Dad was an ambitious, “grand idea” kind of man. With the wedding gift and business loan, he and mom opened a mechanized laundry rather than face mountains of hand ironing. In the pre-steam iron era, people had to hold the iron with one hand while dipping their free hand into a bowl of water to scatter droplets onto dried out areas of freshly washed clothing. The good ones turned this action into a high art, able to cover a large area with one flick of the hand. Dad once demonstrated his own time saving technique, perfected in his home village in China: holding a mouthful of water, he “sprayed” clothing by mouth, claiming it was superior because it was faster.

Although irons had become electric, Grandpa preferred the old way: heating and re- heating a flat iron on the surface of the wood burning stove. This relic of another period might have come with the building, but our parents preferred the gas stove next to it.

Commercial washers and pressing machines required more space than a typical retail storefront had in either the second Chinatown three blocks over or the newer one on King Street. Dad found the perfect place – a long-abandoned, three story, near windowless commercial building at 40 5th Avenue South. The business took up the ground level, the second floor became a kitchen and dining area, and the third floor, with its open floor plan, served as our “bedroom.” Former childhood playmates recall the near windowless second and third floors as “…like coming into a cave.”

Inside the front door entry was the service counter, to the right of which was the shirt pressing stations, consisting of a set of four machines for pressing business shirts: a cuffs and collar presser; and beside it on the right, the sleeving machine. Next to that was the body presser, and lastly, the folding machine.

The pressers were set up in a circular position for a team of three operators. A commercial laundry basket full of newly washed shirts would be rolled over to the first station where the pressers gathered to untangle the damp shirts in preparation for step one. The first operator then laid out cuffs and collar onto a similarly shaped presser, hit a button and hissssss! The upper “jaws” snapped down for a factory set time then auto opened. Snatched off the cuff-collar presser by the same operator, she then hung the shirt on a knob at the side of the machine and cuff-collar press another shirt.

During the cuff-collar pressing interval, the same operator stepped sideways grabbing an already cuff and collar pressed shirt to fling and fit the sleeves onto upright “arms” for sleeve pressing–somewhat like a toaster in that once the shirt sleeves went onto the “arms;” the press of a button popped them backwards into double sided pressers. Manually controlled flaps could adjust for wider sleeves. When done, the presser auto popped the sleeve arms back out. The operator then hung it on the next knob for the body presser, who “dressed” a torso-like revolving machine.

Like the sleever, adjustable flaps changed the width of the torso to accommodate larger size shirts. By stepping on a pedal, the operator whirled the “body” 180 degrees to the opposite side, where it was clamped front and back by hot presses that auto opened. As the “torso” whirled back to the operator, she removed it to a center rack for the final step: folding. She also inspected for shirts needing button replacement or mending. These were set aside for mending and button replacement.

The folder seized a completely pressed shirt, fastened the top button, secured the shirt collar down in the folding machine, and pressed a button for auto fold to take over. The final steps were banding (with a paper band around the shirt with a pre-printed message: Enjoy the Day!) and collaring (inserting a carboard strip into the collar area to keep it from being crushed) when stacking and wrapping final bundles of shirts in blue paper.

A well-coordinated, three-person team could turn a damp shirt into a pressed and ready to go product in a couple of minutes at the reasonable price of 22 cents per shirt. Compare that to how long it would take to hand iron, hand fold, band, and tag board collar a shirt! Behind the shirt unit were two pants pressers. At the very back were the commercial washing machines, starching and bleaching bins, an electric treadle sewing machine for mending, and a hand cranked button replacement machine.

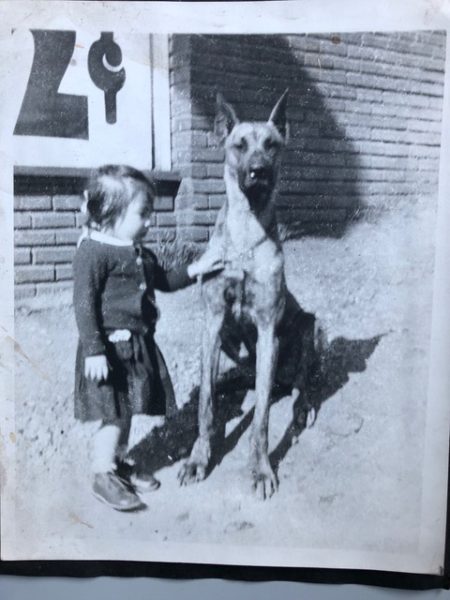

Note Linda’s footwear–a lost shoe problem solved!

The electric treadle sewing machine mesmerized me. The mender positioned a torn garment under the needle, stepped on the treadle and the needle churned up and down as the sewer guided the tear back and forth and sideways. I wanted to do it, too! When she went on break, I toddled over, put one hand under the needle to pretend I was guiding a garment, and stepped on the treadle. My screams brought everyone running. The nearest person scooped me up to stop the needle from punching into my fingers. I think that’s why I’m mostly left-handed today.

As teens, Linda and I learned to operate all of them, but my favorite was the folding machine. Because she had quicker reflexes, she was the lead on the cuff-collar combo and the sleever. Brother Eddie, as the tallest, operated the body presser but was needed more as a washer and in high school, a pick-up and delivery driver to our outlets and wholesalers. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Accessible only by a steep, wooden staircase, our kitchen and eating area sported an old gas stove and oven—the wood burning one unused and forlorn; our “dining table,” a well-weathered picnic table, and a couple of benches that Dad had heisted from a park. The day’s Chinese newspapers became disposable tablecloths, easy to fold and toss after dinner.

On the top floor, the windowless south wall was the main bedroom wall. The only room with a lock on it was the tiny nearby “bathroom.” Behind its locking door were a toilet and a sink. I considered it the only safe place to hide from Dr. Bo Luke’s house calls for vaccinations. We kids started running when we saw him enter with his black medical bag. We thought we were smart, scattering and running, but there were enough adults to corner us. Frantic, we made a break for the bathroom and locked the door, refusing commands to come out. Sanctuary was fleeting. Dad picked the lock in seconds. Trapped! He pulled us out one by one, holding down each for a quick exam and vaccination, ignoring our shrieks and screams. Those giant needles really hurt!

Crawling and playing “horsie” on the wood floors resulted in frequent splinters in our hands and knees. De-splintering by the nearest adult became routine. Sometimes the splinters were so deep that Dr. Luke had to come by to remove them with special tweezers.

While I slept near my parents on the third floor, Linda and her crib were exiled to the 2nd floor. Dad didn’t like to hear crying. One night Mom and Dad woke up to her pitiful wailing, different from her usual crying. I woke up, too. Sleepily, I followed them downstairs to see what was the matter. We approached her crib.

I heard skittering as dad turned on the light. Peering into the crib, mom asked, “What’s making her cry like that, so loud!” as she rubbed Linda’s back. (In those days, all babies were put on their stomachs to sleep.) Dad replied, “It’s the rats. They smell the milk on her and come out. They’re gone now. Let’s go back to bed.” Then they went back upstairs. I stayed behind, thoroughly awake. Reaching as far as I could with one hand between the crib slats. I patted her gently on the back, saying, “Don’t cry, don’t cry, the rats are gone,” even though I didn’t know what a rat was.

Soon after, Brock came into our lives and slept near her to deter the rats. Dad didn’t like cats, and mom was against pets since she always ended up with their care and feeding. Brock was a speckled Great Dane with gigantic, pointy ears. He towered over Linda and me. We loved playing with him, imagining he was a horse. Mom and dad allowed us to play in front of the laundry, but only on the sidewalk, under Brock’s steady gaze. Mom warned us, “Stay in front, never leave the sidewalk.” As dad recounted to us in high school, a rambunctious Linda tottered unsteadily across the sidewalk, stepped down from the curb, and continued out into the traffic lanes of 5th Avenue.

As soon as she stepped off the curb, Brock snapped to attention, leaping past me into the street, grabbing her by the back of her diapers with his enormous mouth. Slowly walking backwards, he tugged her gently back onto the sidewalk. Mom snatched her up, babbling, “Don’t ever do that again! Stay on the sidewalk, stay on the sidewalk!” Brock earned his place in Heaven that day.

After her miscarriage, Mom had our baby brother, Eddie, in 1950. By then, Linda and I both slept near our parents. Our bed? By day, a two-person sofa at the foot of their bed. It was my job to pull the sofa cushions onto the floor for Linda while I slept with a blanket on the remaining bounceless part of the sofa. In the morning, she helped me put the cushions back, and it became a horse, a car, a trampoline, whatever we wanted until bedtime. We also played with a box of odds and ends of military gear that Dad kept in a box under the bed, what I now recognize as a gas mask, flight goggles, even a gun. When we tired of rummaging in the box, we pushed it back under the bed, until Mom caught us. The box vanished.

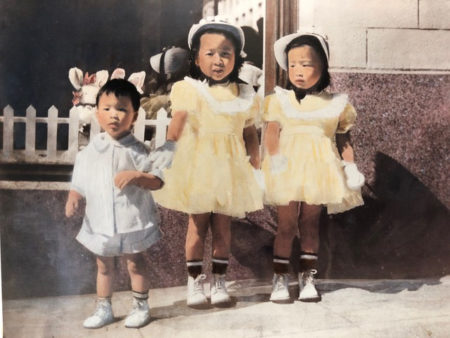

Eddie is in front of the 2nd, seldom used entry of the laundry. Linda and I took full advantage of that fire truck. His legs didn’t reach the push pedals so we pushed him up and down the sidewalk and as soon as he went inside, we took turns pedaling ourselves in it.

As Day-day, Big Sister, my other nightly chore was getting a “bed” ready for our baby brother. Dad had acquired a sturdy chest of drawers. After preparing Linda’s sofa cushions, I raced to the bureau and opened the 2nd drawer from the bottom, carefully placing and smoothing out his blankie in it. Finally, I added in his tiny baby pillow.

Although too young to count, I nonetheless helped mom with the day’s receipts. She assigned me to organizing the coins, first sorting them into piles by size and color. Then she made a stack each of pennies, nickels, dimes, quarters, and 50 cent pieces. She challenged me to make more stacks of the exact same height. After inspecting my stacks for the exact height of hers, she showed me how to put them into paper rolls, folding the ends over to seal them in. When I got a little older, I graduated to handling paper money—turning them right side up and separating them into groups by the pictures of heads on them. I learned to count by listening to the soft intonations of her Toisanese as she handled the dollar bills: “Yit, ngee, slahm, slee, mmm, loke….”

One day a customer asked dad if we had a T.V. Dad said no; the customer offered us his. We were so excited! A black and white TV was a luxury few could afford. All dad had to do was pick it up. But when Dad brought it home and plugged it in, the main tube didn’t function. It sent Dad into a curse-filled rage; the customer couldn’t be found, having moved away without a forwarding address.

Other entertainments were family picnics by flowing rivers, Lung Kong Tin Yee Family Association events at Chong Wa, and annual picnics in larger parks. The Family Association headquarters in the East Kong Yick building was too small for all of us, considering we were actually four families: Lau, Quan, Chang, Chew).

One evening our parents took us to see a screening of an old movie, The Good Earth, upstairs in Chong Wa. Everybody’s kids slept through most of it. Afterward, the grown-ups talked about white actors playing Chinese. In my mind, I thought: Chinese must not want to be actors so white people have to do it.

Meanwhile, extended family came and went. Grandpa had remarried in Hong Kong and step grandma gave birth to my youngest uncle the year before I was born. Consequently, grandpa shuttled back and forth from our place to Hong Kong, where he also visited his first born, Goo Ma (dad’s older sister), his two younger sons after dad, Yee Soak (2nd Uncle) and Sahm Soak (3rd Uncle). His year-old son was Say Soak (4th Uncle).

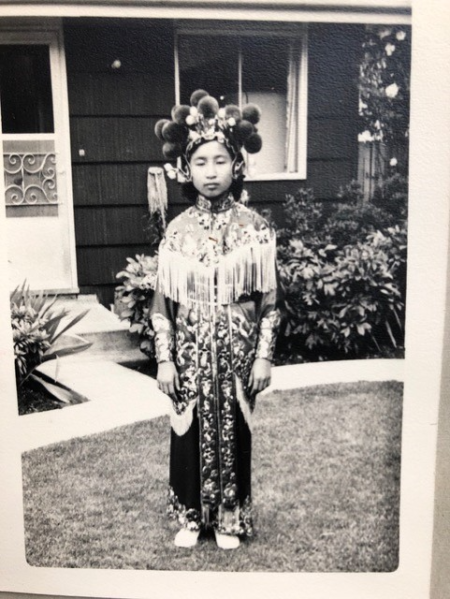

Sometimes grandpa took me on Saturday mornings to watch the newly formed Chinese Community Girls Drill Team, organized by Aunty Ruby. The girls wore bright red, fringed, and sequined woman warrior uniforms, a Cantonese opera design suggested by her husband, Uncle Ping. Hearing the drumming from blocks away, we would hurry to sit on the steps of Chong Wa Hall to watch. Once in a while, we were lucky and saw them in full regalia practicing intricate maneuvers in the street. Nodding approvingly, grandpa would lean down, saying, “Someday you’ll be one of them. Wouldn’t that be wonderful?”

“Oh, no! I can’t! they’re too grand for me!” Grandpa just laughed every time I answered that way.i

Dad’s 14-year-old cousin Ken from Canada spent a summer with us, working for $18 a month plus room and board. He took over the starching vats and shirt collar bleaching bin. After dark, when no one could see them, dad let him drive his wood paneled Mercury station wagon on laundry pick up and deliveries around the city.

Late winter or early spring of 1952, Aunty Alice, mom’s older sister, cleared paperwork for emigration to Canada from Hong Kong, along with her two younger sons, Vincent and Patrick. Uncle Gar-Tat and the two older boys remained in Hong Kong, waiting for their turn to emigrate. Until that happened, Aunty Alice, Vince, and Pat lived with us. Not long after coming to Seattle, she gave birth to Cousin Nancy. Eighteen more months passed before the rest of her family gained visas to Vancouver, BC where they would all be re-united.

New family members required new sleeping arrangements: the third floor became the grown-ups room, shared with baby Nancy and toddler Eddie. We four older ones shared a “Molly Brown” bed on the 2nd floor. The “headboard” was a curved, metal tube with vertical metal rods to support it. The “foot board” was similar but lower, lacking the curve. To make us “fit” the bed better, grandpa came in when he thought we were asleep to straighten out our tangle of arms and legs, tugging us face up, like a row of logs. Finally, he pulled the blanket over us, tucking it in at the sides.

With no bathtubs or showers in our commercial building, we kids were bathed in a large tin wash tub. When we were done, the grown-ups took their turns. Due to using lots of water for the business, the antiquated water pipes frequently leaked and broke down, flooding various areas around the building. Dad and later, Uncle Sam, became geniuses at locating, fixing or inventing solutions for aging pipes.

Grandpa had to teach Aunty Alice how to use the gas stove: turn on a little gas, light a match by the pilot, get your fingers quickly out of the way. Aunty Alice turned on the gas, leaned in closer to see better, lit the pilot, and foomp! A tall flame shot up, searing off most of both eyebrows. Fortunately, she had shut her eyes as soon as she heard the unfamiliar hssss of escaping gas. Ever since, she had to use an eyebrow pencil every morning to augment what was left of her eyebrows.

Although over a year older than I, Cousin Vincent joined me in first grade at Bailey Gatzert in order to learn English. I clung to him fiercely, depending on him to tell me what to do. When it was discovered I couldn’t speak English either, we were put into separate first-grade classrooms to speed up the assimilation process. I didn’t last long, becoming a reluctant, silent participant as other kids grabbed my hands to pull me through rounds of “The Farmer in the Dell,” “Ring Around the Rosie,” “Go In and Out the Windows” and other games.

After a few more days of not speaking without Cousin Vincent by my side, an administrator pinned a note on my coat (I didn’t know I was supposed to hold it in my hand) and said, “Go home,” but I knew it wasn’t 3:10, too early to go home. I ended up sitting on the front steps. A teacher drove me to the laundry, depositing me on the sidewalk—I had not responded to “Get out!” Mom and dad rushed out asking why I was home before school was out.

I pointed at the message pinned to my coat, replying, “I don’t know. Read this!” The note stated I couldn’t come back to school until I could speak English! Mom and dad panicked; they had wanted us to be bilingual and figured we would just pick up English since we were surrounded by it. To get me back in school, they had to promise never to speak Chinese at home again. They kept their promise, speaking Chinese only behind closed doors, and I was re-admitted to first grade, seeing Vincent only at lunchtime. He assured me everything would be fine.

With Cousin Vince now in charge of us younger ones, we were allowed to venture farther away. We liked trooping a few doors north on 5th Avenue to play in an empty lot, empty that is, save for one gnarly, fruit tree. On one of our play days, we noticed it was full of ripe, little apples! We decided to make our parents happy by bringing home the little apples for dessert. Boosting and pulling each other into the tree, we picked the crab apples, filling up our pockets. Little Eddie picked up the ones that fell to the ground. Although we had tried pushing him up into the tree, he didn’t have the strength to hang on to any branches.

Pockets full, we brought our bounty back to the laundry, happily presenting them to our parents to show what we were contributing to dinner. Retribution swiftly followed: Dad raged he wasn’t raising a pack of thieves! Pulling off his narrow, leather belt to lash our legs, he chased us outside shouting, “You kids put them all back, every last one!” I protested no one owned the apples—they were from a tree in an empty lot, but it only infuriated him more, “How stupid can you be? Everything is owned by somebody!” Terrified, Vince, Pat, Linda, and I, trailed by Eddie, ran back to the lot. Dad forced us up the tree, yelling we couldn’t come down until we had put every single crab apple back! We failed at tying them with skinny twigs, failed at jamming them onto bough ends, failed at balancing them on branches. They kept falling to the ground, where Dad waited with the belt if we dared come down. Little Eddie tried to hand up the fallen ones to us— dad wasn’t whipping his legs. Finally, all we could do was shove the crab apples into the larger crooks and angles of the bigger branches. Dad tired of waiting and finally let us climb down, whipping our legs all the way back to the laundry.

We took refuge on the 2nd floor, the five of us sitting in a circle, sobbing and whimpering softly—Dad still didn’t like to hear crying children. Linda looked around to see if the grown-ups were gone before announcing, “Stop crying!” Under our curious gazes, she pulled out a single, large crab apple she refused to put back on the tree. Taking a tiny bite, she solemnly passed it to Cousin Pat next to her. He also took a bite, passing it on until each of us had taken a bite. Tears turned to giggles and suppressed laughter at this rebellious defiance of dad’s order to put all the crab apples back on the tree.

We prospered. Mechanization brought down the cost of washing and hand ironing. Almost immediately, dad was wholesaling for the smaller laundries around the city in a proper laundry truck with a sliding door. Sam Sakai, who had left college to fight with the 442nd during WWII, drove it and in time, became our surrogate father, making up for dad’s parental shortcomings, our beloved Uncle Sam, who toiled alongside mom and dad until he retired decades later. The machine operators were African Americans, the only ones who answered the “Help Wanted” sign in the window.

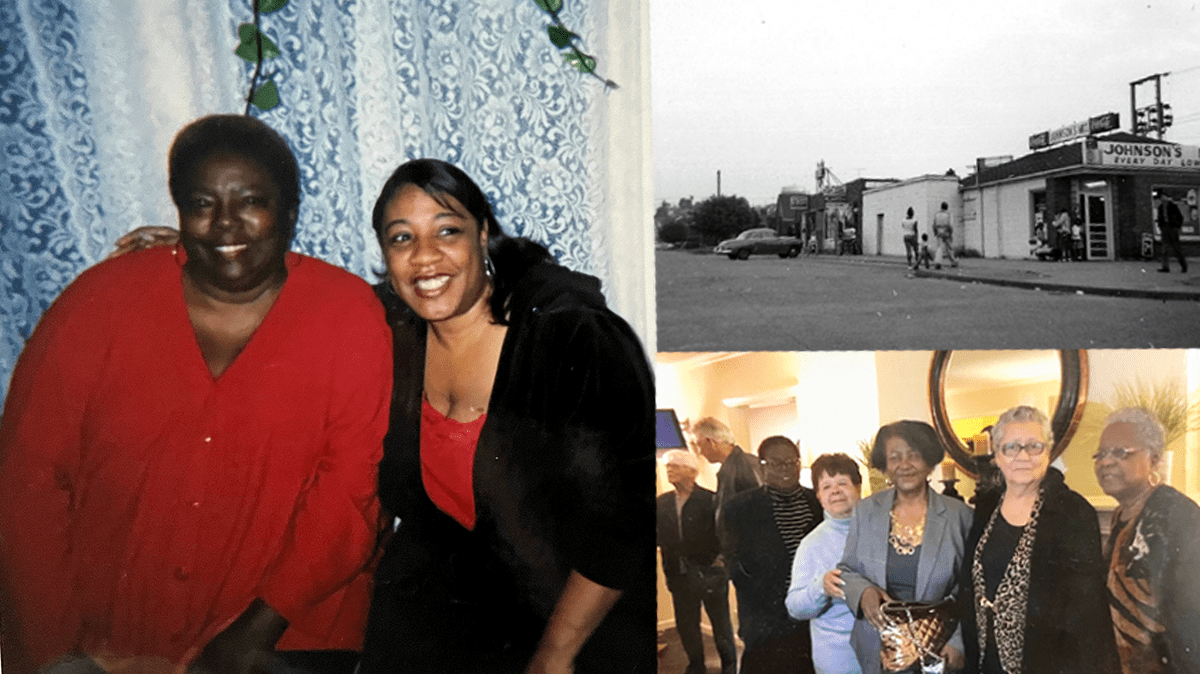

Among them was Mabel Brown. Since she had a nursing assistant background, mom and dad paid her extra to watch over us when they went out to functions that did not allow children. She treated us like her own, correcting our behavior, spanking us when we got out of line, taking us downtown to Kress’ and Woolworth’s for treats. She always wore her white nursing assistant uniform so people would know she was in charge of us, on official business. People stared anyway. Sometimes the rude ones stopped us on the street or came over on the bus to ask what “a colored woman was doing with three little Japanese kids.” With great dignity and pride, she simply said, “I take care of them. And they’re Chinese.”

She bought us our first stuffed animals from a bin in Kress’—a panda bear Eddie named Jasper; a brown bear with movable arms and legs Linda named Zeke, and a pink bunny I named Topsy. We refused to part with them until they turned to worn out shreds of fabric.

On some of the evenings’ Mom and Dad needed Mabel to watch us, she agreed only if she could take us to Bible study with her since it was Bible study night. They didn’t mind. I was already attending Chinese Baptist Nursery School and Sunday School.

We caught the bus and got off near Yesler Terrace. Bible study was in the basement of an old, wooden building. The minister started off with a prayer, a Bible reading, a sermon, and finally, led the singing of hymns. Linda and Eddie fell asleep on the pew. Periodic shouts of “Amen” jerked me awake. I thought it was time to go. I was wrong.

Congregants started rocking back and forth where they sat. Some stood up, trembling and shaking. Mabel remained seated, eyes shut, rocking forward and backwards, praying out loud. Tears rolled down her face. Others called out to God, louder and louder until everyone was crying, moaning, shouting, swaying, praying out loud, rocking. I wanted Linda and Eddie to see. I shook them; they sat up, blinked, and went back to sleep. I watched the congregants in amazement–so different from the sedate Chinese Baptist services! And then it was over, as if some shared, secret signal had sounded. People wiped their faces, straightened their clothing, bade each other farewell and trudged upstairs to the exit one by one. We left, too. I asked Mabel why she was crying. She said she cries for her six dead babies, none of whom survived childhood.

Uncle Sam used to let Linda and me sit with him in the laundry truck. We were fascinated by how he turned the wheel, stepped on three pedals, and moved a lever that went into the floor. One day he parked it facing south on 5th with the sliding door open. He went inside the laundry to get another load to deliver.

Linda saw an opportunity. I yelled, “Stay on the sidewalk!” to no avail. She clambered up into the driver’s seat, turning the wheel, pedaling her feet; but she could reach neither pedals nor that tempting lever in the floor. She lowered herself from the seat and tugged the lever. I was still yelling, “Come back! Stay on the sidewalk! You’re going to get it!” After several determined tugs, the lever moved, and so did the truck. It rolled away, down Fifth Avenue with Linda peering at me from the open driver’s side doorway. Uncle Sam burst out of the laundry, sprinting wildly after the truck, jumping in, and hitting the brakes just before it rolled into the Main Street intersection. A string of “Jiminy Crickets! Jiminy Crickets,” exploded from him. Thereafter, he always shut and locked the truck doors in front of the laundry. Most hurtful, he never let us in the truck with him again.

On July 23, 1951, the year I turned four, Mayor Devin issued a proclamation changing the name of Chinatown to International Center, marking us as forever foreigners. As dad told me decades later, everyone knew it was to keep us out of downtown, Yesler being the boundary between the white downtown business area and the red light district south of Yesler that people of color were forced into by redlining in housing, banking and finance. The area was so notorious that the Paine Field military command declared it off limits to their personnel in 1948. According to dad, and later, Aunty Ruby, the concept was Seattle’s minorities would have an area of our own to stay in. Aunty Ruby and Dr. Luke made known Chinatown’s objections by meeting with the mayor on the day of his proclamation. They couldn’t change his mind.

Dad reacted differently. He never liked being told what to do. As an 18-year-old army recruit, he’d been thrown into the guard house and had his pay docked for going AWOL not once, but twice—for two weeks each time. He didn’t believe in asking permission to leave the base whenever he wanted. And he gave up his father’s Everett restaurant to start a laundry with mom because he hated customer demands, how they snapped their fingers at him and sometimes spit at him while he waited on tables.

He decided to go downtown. But he just couldn’t wander around downtown doing as he pleased. After mulling it over, he thought what could be more harmless than a dad taking his young children downtown shopping? He settled on Easter. We kids were attending nursery school at Chinese Baptist Church on the eastern edge of Chinatown on King Street. Although mom was Buddhist and dad an atheist, she thought we should be Christians to fit in better in society.

The months passed quickly; Easter approached. We were so excited! New clothes! Shopping downtown! Mom refused to go. She was upset at the extravagance of outfits that couldn’t be worn more than once. She kept the household and business ledgers and had to set aside whatever she could to help extended family in Hong Kong.

Originally a B&W, this photo was “colorized” decades later.

On the appointed day, Dad stuck to his plan and drove us to the children’s clothing shop downtown. It was crowded with parents and kids. The clerks were busy helping others, but it was okay with me—more time to wander and stare at everything on the racks! Finally, it was just us in the shop. Our turn! Dad said he wanted Easter outfits for all three of us. A clerk convinced him not only did his young daughters need yellow dresses, but properly dressed little ladies also needed matching bonnets, white gloves, socks, and shoes!

The clerks started wrapping up Dad’s selections, but he asked them to dress us in our new finery to go. Then he sheparded us outside for a photo. Lining us up against the storefront, he ended with, “Don’t move.” But Eddie kept walking towards him as he backed up for the shot.

“Get back, don’t move!” Dad repeatedly re-positioned Eddie. “Stay! Don’t move!”

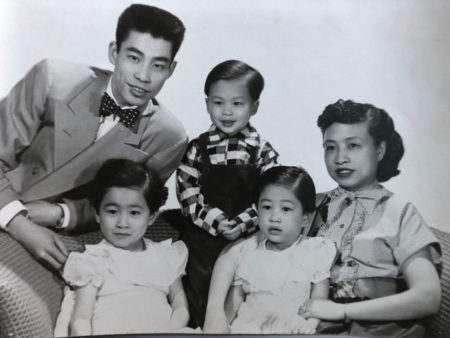

L-R, Back: David Lau, Eddie Lau

L-R, seated: Betty, Linda, May Lau

I had to put out my hand to keep him in place. That’s the moment Dad captured our Easter image with his latest prized possession, a black, Brownie box camera. Post Easter Sunday, he brought the whole family to Uncle Yuen’s photography studio for an official portrait—the second time we wore our almost outgrown Easter frocks.

As business increased, Dad was on to his next big idea: adding a sheet presser, expanding into dry cleaning. For that, we needed a larger commercial space. He found it on Rainier and Massachusetts, not too far from Chinatown; but the building was only big enough for the laundry. Another space had to be found for the new dry cleaners. He found it in Fremont, next to the Baby Diaper Service.

And finally, he and mom had saved enough for a house with modern appliances, bedrooms with walls, bathrooms with a bathtub, and most importantly, our own backyard instead of somebody else’s empty lot!

I don’t remember the move, but it happened in time for me to start fourth grade at Stevens Elementary in 1956.

Betty Lau is a life-long Chinatown volunteer and advocate who spent her early childhood years with family and extended family living above their machine laundry on the NE corner of 5th Ave. S. & S. Washington St. After graduation from the University of Washington, she worked as a copy editor and then became an award-winning teacher and advocate for at-risk youth, especially English Learners (ELs).

Now retired from the classroom, Betty writes and directs an annual National Security Language Initiative Startalk grant for fluent speakers of Chinese or Korean to become public school teachers. She continues to advocate for equity, transparency, social justice and inclusion of Chinatown in city policies and practices, while researching and writing about Chinatown/Chinese community history.

FOOTNOTES

i. His wish for me came true a few years later in 1959 when Aunty Alma Lew asked me, after Sunday School, to help serve at a church dinner. Mom and dad gave permission for me to go but when dad dropped me off at Aunty Ruby’s restaurant, I discovered I misunderstood in the noisy aftermath of church that Aunty Alma had actually invited me to be a guest at a drill team recruitment dinner, where Aunty Ruby explained to us 12 year old girls we would be representing the Chinese community and helping to build bridges of understanding. I joined, but Aunty Ruby had to call my parents to get their permission. Permission granted, with the understanding that Aunty Ruby would arrange transportation to and from Chinatown. She arranged for me to be in Consul General Yu-chang Lu’s pick-up group. He was the first Consul General appointed by the Republic of China to visit Washington State. His daughter Beatrice became a lifelong friend.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With gratitude to the native peoples of these lands who sheltered and hid Chinese fleeing from the Seattle Expulsion of Chinese in 1886; one of whom possibly being my grandfather, as told to me by my father.

In memory of David and May Lau, Alice and Gar-Tat Louie, Sam Sakai, Mabel Brown, Ruby and Ping Chow, and our dear Brock.

Thanks to: sister Linda, brother Ed, sister Irene, brother-in-law Norm James, Cousins Ken Lowe, Vincent, Patrick, and Nancy Louie, nursery school friend Rick Chinn and former visiting childhood playmates

Also:

City of Seattle Archives

De Barros, Paul. Jackson Street After Hours

Mar, William. Mar Family Remembrance Album

Puget Sound Archives

Seattle Post Intelligencer

Seattle Public Schools Archives

Seattle Times Archives