Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

by Beverly Aarons

In The Before

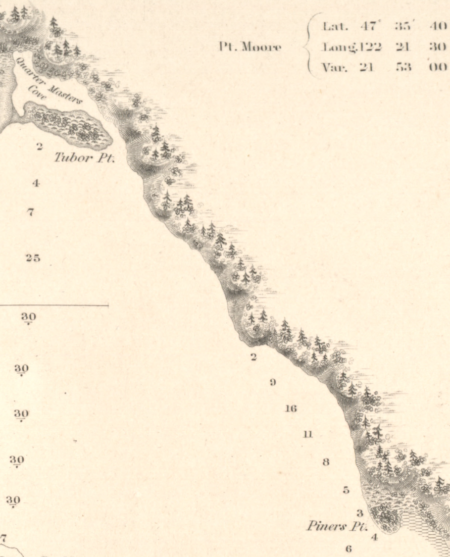

In the spring of 1785, earthy toned mudflats glistened in the moonlight during low tide in the place called Sdzidzilalitch (little crossing-over place)i. Pacific tree frogs sang their mating chorus (kreck-ek, kreck-ek) in the marshy forest which brimmed with fir, oak, cedar and other trees, some now extinct. The People of the Inside (Duwamish, Suquamish and Muckleshoot) would have emerged from their longhouses, perched on a patch of land not submerged by high tide, to celebrate the coming of spring — their skin painted with vermillion, and their songs welcoming spring’s promise and bounty. Seven years before George Vancouver sailed his vessel through the Strait of Juan de Fuca into the unchartered and dangerous waters of the Whulge (Puget Sound) and 70 years before the Treaty of Point Elliot, Sdzidzilalitch was where The People of the Inside socialized, traded, formed alliances, and shared knowledge. Women would have canvassed the soppy tidelands, smooth, wet sand oozing between their toes as they fished for crabs in shallow tidal ponds. Cedar bark baskets could have easily held the day’s crab catch as well as mussels and clamsii.

The Great Change

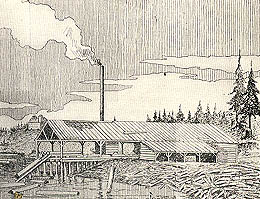

In March of 1853, Henry L. Yesler’s sawmill opened for the first time. Planted firmly in the shadow of Sdzidzilalitch, the sawmill clattered and hissed and drowned out the tree frog mating songiii. Men of the inside and white settlers, fed many hundred year old trees into the mill’s jaws. The machine of the settlers spit out lumber profits on one end and piles of sawdust on the other which slowly filled the tidelands and threatened the rich fishing grounds that had nourished The People of the Inside for 500 years. Ships carried the severed trunks of old trees to California, Hawaii, and beyond. And by 1910, the Pacific Northwest would become the logging capital of the United States and Sdzidzilalitch would stand naked, stripped of her forest.

The Terraformation

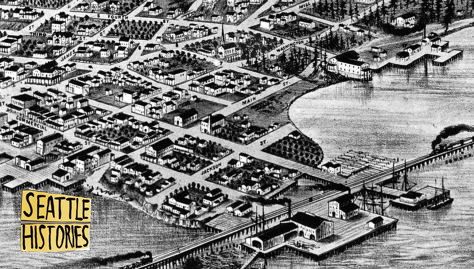

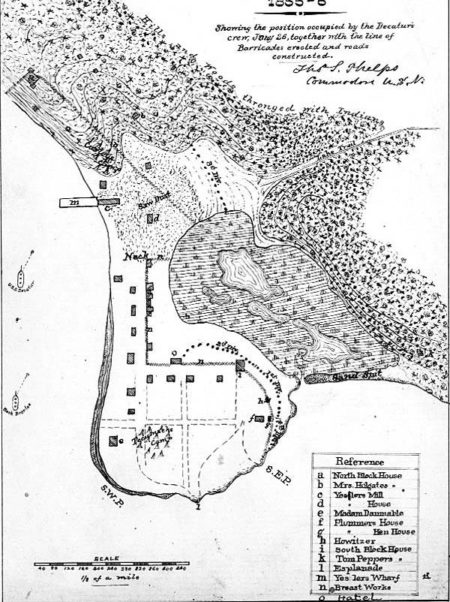

White settlers filled the Sdzidzilalitch tidelands with sawdust and the tops of giant hills that had been felled with settler tools. They made hilly places flat and wet places dry. And they drew invisible lines on the land creating plats and parcels and blocks and lots, and most importantly – ownership. Block 17 is nestled in the heart of David Swinson “Doc” Maynard’s plat which was granted to him in 1853 under the white settlers’ law: Every white male citizen who is at least 18 years of age is entitled to a 320 acre claim in the Territory of Oregon (which included what is now called Washington), and if he is married an additional 320 acres for his wife. Doc received 640 acres in what is today called Pioneer Square.

The People of the Inside could no longer survive off the land in Sdzidzilalitch so they worked as fishermen and loggers, and sold shellfish and baskets. A son of The People of the Inside, Chief Si’ahl (Seattle), became a Catholic in 1830, befriended Doc Maynard in 1851, and eventually earned a reputation as a “friendly Indian.” In 1853, the city was named after him but by 1865 The People of the Inside and all Indians were banned from living within the city borders.

Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.

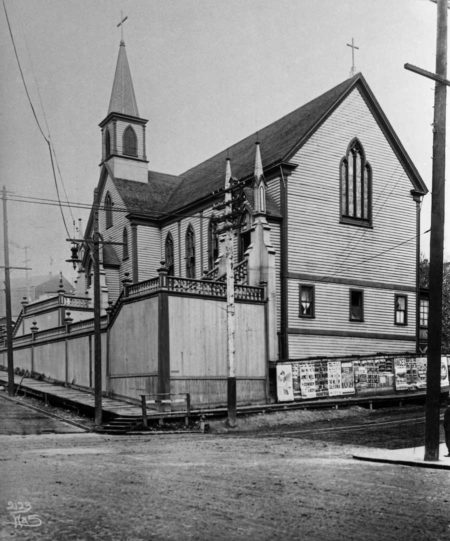

Father Francis X. Prefontaine’s flock of 10 parishioners – Catholic and Protestant – might have said this prayer during a Sunday mass while crammed into the 29 foot by 50 foot church, Our Lady of Good Help. And they might have prayed for the sinners who patronized and worked at the brothel across the street. The young priest had been warned that Seattle was a “lost cause” but Father Prefontaine zealously raised $1800 to build the church on Block 17 and to expand it in 1882. By 1889 there were 3,000 parishioners. Sdzidzilalitch had a new religion.

Money Is God

Beginning in 1896, over 70,000 people streamed into Seattle on their journey to the Klondike region of Yukon, Canada – it was the gold rush. Seattle didn’t promise gold but it did provide food, blankets, tools, and other supplies to gold seekers before they continued their journey north. It was the right place and time to make a fortune as a business person in Seattle, and people like Charles D. Stimson, a timber baron and real estate powerhouse, got rich in that time of prosperity. Stimson seemed to run the town. He owned a sawmill and numerous properties and automobiles (which he and his son raced on Seattle streets), and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s society pages often mentioned that the Stimson family had entertained diplomats, businessmen, and other powerful people. Interestingly, Stimson had a penchant for purchasing and developing triangular properties because he believed they were more profitable due to the increased frontage. So after purchasing Block 17 from Father Prefontaine in 1904, he hired architect C. R. Aldrich to build the Exchange Building, a 19,800 sq ft fireproof warehouse constructed of steel and concrete with 462 feet of street frontage.

NEW ROUTE OF TRAVEL MAKES PROPERTY VALUABLE

In 1906, 3rd avenue had been extended and a new road was created – Prefontaine Place South – which would become a major thoroughfare through which all of Seattle’s streetcars would pass. The Exchange Building was a Class A building and its location made it the most valuable property in Seattle’s southern business district. By 1907, one of the oldest manufacturing companies in Seattle, Pacific Wire and Plating Inc., became its cornerstone tenant. Sdzidzilalitch, once mudflats cuddled by a canopy of trees, was being transformed into a budding metropolis.

PACIFIC WIRE AND PLATING WORKS, Incorporated

Boom Times

In 1918, there would have been at least one or two drunken men stumbling down Prefontaine Place on any given day. If you gave them a glance, you probably wouldn’t see a liquor bottle – prohibition had already come to Seattle – but anyone within a foot of any inebriated man might have smelled the strong liquor odor pulsating from his lips. And Samuel H. Prince, the owner of Prince Drug Company located in the South End Market (formerly the Exchange Building), would have been familiar with that stench as he was one of the few people who had a license to sell alcohol. But it doesn’t seem that he “played by the rules,” as his business partner, R.G. Stephens, was arrested by Seattle’s Dry Squad for illegally storing 998 bottles of wine, liquors, champagnes, and other spirits in a warehouse only a block away. There was money to be made in selling alcohol and Prince and Stephens’ profitable business practices were on the Dry Squad’s hit list and in violation of the city ordinance. The liquor was seized but only six months later the Supreme Court found that they had done nothing wrong. A licensed druggist had a right to store their alcohol in a warehouse if they wanted toiv.

By 1920, Seattle was officially a boomtown. Six years earlier, the Exchange Building had been remodeled and became South End Market which eventually became known as the Market Square. Every streetcar in town rode past the market which housed all kinds of businesses: shops that sold produce, poultry, fish, dairy, tea, coffee, and pastries, but also tailors, delicatessens, barbers, shoe repair shops, cafes, law offices, a Dixie Motor Company dealership which sold Dixie Flyers for $1,665, and the Tashiro Hardware Company established by Kanjiro Tashiro and his wife Toshi.

Nihonmachi

Kanjiro Tashiro was still struggling to speak English when he welcomed Tashiro Hardware’s first customers in 1917 — his daughter, Billiee, would translate for him. But even before his shop made Block 17 home, Tashiro had an entrepreneurial spirit. In the 1880s, while still living in Japan, he purchased used chisels and sharpened them for resale. So when he opened his hardware store, fine imported Japanese tools were his specialty. But he didn’t just sell Japanese tools, he developed an understanding of what customers wanted and made sure that his shop offered it, and that attention to customer needs grew his shop’s popularity over the course of 25 years. Then the country went to war, and Tashiro and his family were ordered to “evacuate” which meant they had to close their store, leave their home, and submit to incarceration at a government run internment camp for people of Japanese descent. On March 6, 1942, Kanjiro Tashiro advertised an “Evacuation Sale” ad in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer for all inventory in his hardware shop – up to 50% off everything.

EVACUATION SALE: FISHING TACKLE HARDWARE

There were 7,000 Japanese Americans living in Seattle in the 1940s and 12,892 in Washington State. And like most Japanese Americans living in Seattle, Tashiro and his family might have gone to Puyallup and then to the Minidoka Relocation Center near Hunt, Idaho. And while there is no record of the Tashiro family’s incarceration experience, they could bring only what they could carry, so like many people they might have stored their personal belongings at a church or the home or business of friend. The winters were harsh in the incarceration camp, sometimes dropping to 20 degrees below zero during winter and reaching 115 degrees at the height of summer. Most Japanese Americans were incarcerated for 3 or more years. After the war, Tashiro reopened his store and it would remain on Block 17 until 1980.

THE NISEI PROBLEM NOW AND LATER

Death and Rebirth

In 1945, Jacob Kaplan[i] purchased Market Square, which had become known as the Market Center building, and he established a paper products operation onsite. Born in Poland in 1886, Kaplan immigrated to Seattle in 1900 where he opened the Kaplan Paper Company with only $65 in capital. Eventually, the building took on the Kaplan name.

In 1976, the building was rehabilitated and hosted a vibrant LGBTQ scene – there was one gay bar, a lesbian bar, and one gay owned restaurant in the 70s and 80s.

In 1984, Tashiro-Kaplan Block (Block 17) was optioned for purchase by Jan Mohammed. Mohammed was a former Kenya governmental minister living in Vancouver, BC Canada and Seattle at the time. Mohammed wanted to add 6 floors to the Kaplan building and 5 floors to the adjoining Tashiro building. The $16 million expansion plan was part of a much larger revitalization strategy for the area. But the design plans never became reality; instead both buildings were purchased by the county when the construction of a new traffic tunnel was announced for 3rd Avenue.

The Phoenix

“What do you consider a healthy community?” Activist Catheryn Vandenbrink takes a sip of her coffee, then gestures toward the window and crowded Pioneer Square. “Is it just bars, stadiums and condos? Because that’s what this place could become.”

–Seattle Times, November 4, 1997

As tourist footsteps crush the fallen leaves, Vandenbrink details her fears of neighborhood change.

“This is a historic and artistic district. I’ve lived here 11 years and it’s truly vibrant.”

In 1997, Sdzidzilalitch (Pioneer Square) contained 500 very low-income apartment units, 1,000 shelter beds, 100 market-rate apartments, and 200 high-end condominiums. There were about 300 artists living in the low-income units. But a proposed new stadium to replace the Kingdome was just on the horizon and large developers were positioning themselves to reap large profits by redeveloping their units which would displace Pioneer Square’s low-income artistic and cultural workers. Artist and activist, Catheryn Vandenbrink, along with others in Pioneer Square, gathered their forces and took action to save affordable housing for artists. Artspace, a non-profit arts advocacy organization turned artist housing real estate developer, came to the table and developed the Tashiro-Kaplan property into the 50-unit Tashiro-Kaplan Artist Lofts in 2004. When the building opened, it was home to artists of all disciplines as well as artist studios and galleries. At one point there was a full café in the corner commercial unit abutting Washington and Prefontaine, and the artist residents organized a street festival and opened their studios to the public once a year. The building became a go-to location for First Thursday Art Walks and a real community was born. Block 17 had become home to creative people who were breathing new life into the neighborhood.

Plague

Today (2021), Block 17 artist residents battle for survival as a pandemic rages on around them – none of them have died from the virus but some have lost jobs and opportunities. The café on the corner closed soon after the governor ordered lockdowns and some people moved out because they could no longer afford the rent. There is so much suffering in Sdzidzilalitch: people with no homes, people sprawled on the ground with needles stuck in their arms, people who yell at ghosts, and other people who attack or kill with little or no provocation. And many of the artists suffer too but they still create – they paint, they dance, they write, they capture the world around them in photography and film and music, and they try to imagine and manifest a new reality.

Creating Reality

Tucked in the corner of Block 17’s Tashiro Kaplan Artist Lofts, there’s a woman in her seventies who began painting in her forties, now she runs a small gallery with an artist collective. There is an accomplished and award-winning painter who was born in Cuba. There’s a spray paint artist, a cartoonist, a textile artist, a gallery that hosts national and international artists whose non-commercial works don’t fit neatly into a traditional gallery setting. There are artist collectives, there’s a Butoh dancer, and there are playwrights, poets, guitar players, and experimental artists who cross boundaries, and more. They are creating reality. They are writing Block 17’s new story.

Beverly Aarons is a writer and game developer. She works across disciplines as a copywriter, journalist, novelist, playwright, screenwriter, and short story writer. She explores futuristic worlds in fiction but also enjoys discovering the stories of modern day unsung heroes. In August 2018 she produced a live action game and event where community members worked together to envision an economic future they truly desired to leave future generations. She’s won several awards and grants for her work including the Guy A. Hanks, Marvin H. Miller Screenwriting Award, Community 4Culture Fellowship, Artist Trust GAP Award, 4Culture Creative Consultancies Award, and the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture smART Ventures grant. She’s currently working on a series of nonfiction stories about ordinary people doing extraordinary things in their local communities, developing the video game Rent Hike, teaching teens game development, and producing an immersive theatrical experience about the future of human migration.

Footnotes:

[i] Using historical photos, maps, and the books: Buerge, David M. Chief Seattle And The Town That Took His Name (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 2017) and Klingle, Matthew, Emerald City: An Environmental History of Seattle (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), I recreated scenes of what Seattle looked like environmentally and imagined how individual people might have lived. I recreated multiple scenes in this article to facilitate a more immersive experience for the reader. [ii] Stewart, Hilary, Cedar: Tree Of Life To The Northwest Coast Indians (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995) [iii] In an effort to discover what it was like to live in the early settler days of Seattle, I researched what things sounded like such as the sounds of a sawmill and the sound of tree frogs. [iv] “Druggist $7,000 Stock Taken From Him For Second Time In Two Years – Violation of City Ordinance Denied Him,” The Post-Intelligencer, January 25, 1918, page 1. [v] It’s interesting to note that Jacob Kaplan was a Jewish, Jan Mohammed was presumably Muslim, and that the first property developed on Block 17 was a Christian church. It seems that people of all three major monotheistic religions had a major hand in shaping Block 17’s history. [vi] “Space For Creation – A Seattle Symposium” in Seattle Times, November 4, 1997 page E1 [vii] Local Historian, Stephen Edwin Lundgren suggests that the black and white photo of Tashiro Hardware building may have been taken during the 1980’s based on the fact that “the Imperial House at 530 South Main (tall tower seen in the background left) was built in 1979, and the “Cambridge low tar cigarettes” advertisement (billboard) was circa 1980.”