Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

The CD

By Princess Shareef

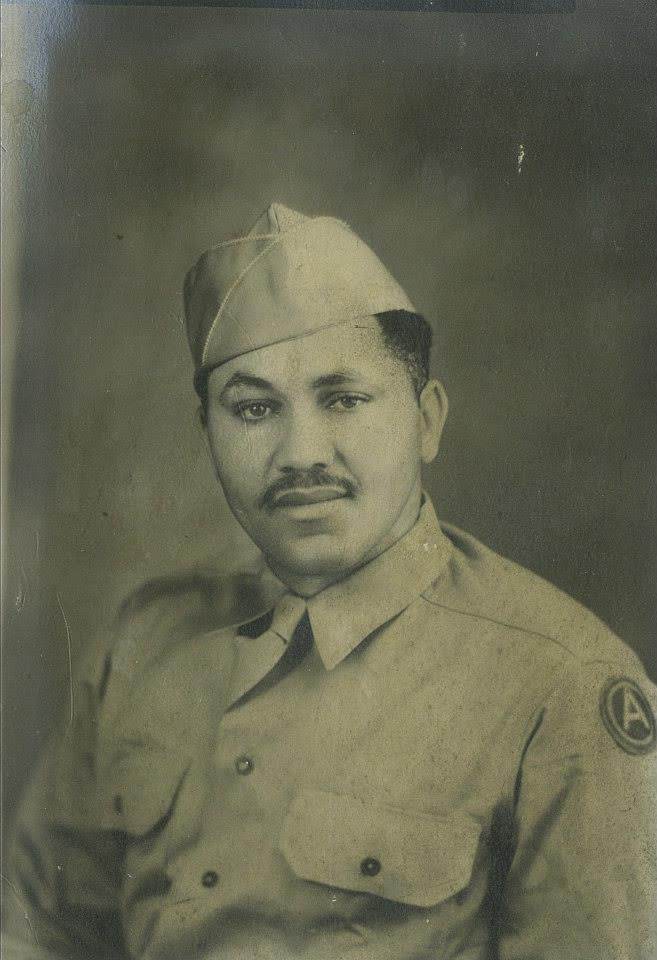

My parents migrated to Seattle from Texas in 1948 along with many other African American families after WWII. My father, a veteran, used his VA loan and bought the house on Alder Street for $28,000. He and other Black men worked in the shipyards unloading cargo. Though they weren’t paid as union workers, the money was better than most jobs they could get back home in Texas. My mother was a maid in Broadmoor. Broadmoor was, and still is, a gated community in the city’s Madison Park.

African Americans followed the ebb and flow of migration to the Central District (CD). When I was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, the CD was one of the few places people of color could purchase a home. I grew up there. A neighborhood with my friend Mae Woo and her family living on one side of our house and the Zimmermans on the other. The Gossett and the Perkins families lived at the other end of the block and the Delgardo’s lived across the street.

Mr. Fujita owned the small mom and pop store on 19th and Alder. That’s back when a family could have an account at their local store. My dad paid up the account every Friday.

Our house was a place where folks hung out on Friday nights after work. My dad named it “The House of Joy.” At the end of many work weeks, I remember grown folks shooting dice or playing dominos and drinking beer. My mother often served up fried fish with smoky red beans and rice, or drew upon her Texas roots and made enchiladas with red sauce. The jazz and soul music wafted throughout the house just loud enough to hum along with and not loud enough to drown out the dominoes trash talk. My dad used to call me into the living room where a blanket was laid out on the wooden floor. There the men, still in their work clothes, were shooting craps. “Blow on these dice for good luck baby,” he’d say, then he’d tell me to pass around his hat for his friends to drop money in. That turned out to be my allowance.

On Saturdays the Zimmerman’s still walked to their synagogue, which has since become the Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Center, and Black women all over the community were in beauty shops with their heads laid back, getting the week washed away. As teenagers, we found out that if you knew someone at the door you could hang out at the over-21 Checkmate club on 23rd Ave.

Former County Councilman Larry Gossett often jokes about changing my diapers (that never happened). In my central area world, my first crush was on Larry’s younger brother Ricky. I don’t think he ever knew.

A little later on, when my brothers were teenagers attending Garfield High School, I would often hide under the dining room table when they had house parties. Or at least I thought I was hiding. My brother Robert always found me and dragged me out. I was barely there long enough to see the slow dancing begin.

The best barbeque in the neighborhood was found at Hills Brother’s BBQ on 21st between Jefferson and Cherry. It was appropriately nicknamed “Dirty Fingers” because often times the slice of white bread placed on top of each order had barbeque sauced fingerprints.

I was baptized at Mt. Zion Baptist church by the new minister in town Samuel B. McKinney. The churches in the CD like New Hope, Goodwill, People’s Institutional Baptist, St. Therese and Immaculate Conception all thrived. They were sanctuaries from our worldly woes and a rallying place for the community’s social justice efforts.

When relatives moved up here to Seattle, our house was the first place they stayed. Cousin Junior, Mayola’s oldest boy, stayed in the back bedroom. Aunts, uncles, nephews, nieces and my brother and his new wife took turns living in the three-room apartment in the attic. Those cousins from New York who weren’t really cousins stayed just a while and went back home to Brooklyn.

In the summer we spent time at Madrona Beach. I remember my cousin from San Antonio, seeing Lake Washington for the first time, calling it a “swimming hole.”

The Rotary Boys Club, as it was named then, was a haven for neighborhood basketball. My brothers spent most of the summer practicing or playing ball there and at other parks around the neighborhood. My husband remembers playing basketball at the park for hours, with anyone who showed up. Hogging the ball was frowned upon. Appropriate etiquette was to pass the ball.

In Jordan Drugs on Cherry, we saw a Black-owned pharmacy with Mr. Jordan working as the pharmacist and Mrs. Jordan running the store. You didn’t play with Mrs. Jordan. Across the street was Blumer’s Deli, they left in the sixties after some “Do the Right Thing” kind of conflicts.

There was the Black dentist, I can’t remember his name, whose office was above Mayrand’s Drug store. He’d been an Army dentist and to us kids he acted as if he still was. “You can take a little pain, can’t you?” he’d ask.

Dr. Homer Harris, a dermatologist, once made me put my hand on a mirror to ground myself to avoid being shocked. I guess it worked.

Before Ms. Helen had her fancy restaurant on Union, she had a small place with a couple of tables and great food.

Before Douglass-Truth Library was Douglass-Truth library it was the Yesler Branch. I spent many hours on Saturdays in the stacks, looking for stories about me. The librarian led me to Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, and later Toni Morrison, who spoke directly to me with her writing.

Huey P. Newton came up to Seattle to sign the papers for a house, right across from the Rotary Boys Club. The Black Panther Party used that house for its free breakfast and healthcare programs. The community supported those young men and women in Black berets and leather jackets because they recognized them as their sons and daughters whose mission was to actually protect and serve.

I grew up in this community knowing that not every community was like mine, and that was okay. One of my favorite photos is one with my brothers Willie and Robert, in the front of our house arm on shoulders with Red Perkins, Larry Gossett and the Delgardo boys. It symbolized the neighborhood. Those who lived here felt comfortable here, accepted here, safe here.

I reminisce about my childhood to highlight the connection we all, as humans, have to our communities. Not just a neighborhood, not just a place designated on a city map, True regardless of your financial situation, because money doesn’t really matter when you think of home.

Do the people you live with love you? If so, then the sleeping head to foot in the same bed with your brothers and sisters, doesn’t matter.

Do the people in the community encourage you? Then they understand when you have one dress for special occasions and wear those same patent leather shoes every week. So, when you stand on stage to recite that Bible verse or that poem, sing that song, or play those drums they make you feel special.

Are there special events in the community to celebrate your roots? The piece of Africa, Mexico, Philippines, China and Japan in you? The Texas, Alabama, Louisiana in you?

When people ask you if you remember Ms. Parker’s little sister’s best friend, you’d say, “Oh, yeah.” Because you did. You see, there were connections.

When you walk down the street or pass folks in the grocery store do they look at you and speak? Do they see you?

Do you see your face in the leaders of the community? Does that make you believe that you could lead also?

When folks need support, is the community there?

When others try to steal who you are, is there a place you can just be yourself?

All these things mean community to me. That’s what the CD was for me.

Now those who live in my neighborhood seldom speak. They do not acknowledge my existence. They lean over fences and talk to each other about being pioneers and remind me of those who “discovered America”.

There are no more Dirty Fingers or Ms. Helens. Restaurant food goes unseasoned in order to appease a bland palette.

One day, way back, I was in Catfish Corner waiting for my order of filet and fries to go, when the song “Street Life” came on. As I always do my foot started tapping and I was bopping my head and humming. It’s a catchy tune. I looked around the restaurant and saw other customers doing the same. The lady at the counter was moving to the music and because of the way Catfish was designed you could see past the counter into the kitchen. I could see the cooks doing the same thing.

Another restaurant took the place of Catfish Corner. I’ve only been there one time, but there was definitely no head bobbing going on.

A few years ago, a young man was visiting my house, the same house I grew up in. He looked around and said, “Is this all there is? All the bells and whistles are upstairs?” he asked, referring to the house built in 1912. “Yep” , I said, and made no further comment. He couldn’t have known. I danced for my father there. I learned about family love there. My mother passed away there. My son said his first curse words there when he thought neighborhood fireworks had “messed up” his grandpa’s new car. He was four.

I see that the people who lived here have been pushed further and further to the south and that those shoving their “manifest destiny” down our throats believe it is their privilege.

The landmarks are gone, and I don’t recognize this CD. Apartments, formerly not allowed in what was a single-family dwelling neighborhood, have crowded out all the character and personality. In fact, it’s not even called the CD anymore. Where I live is called Squire Park. A name they can use to erase the history of this place.

I know the land on which my community was built was originally the land of the Duwamish people and though there is no comparison, I understand a little about how they must feel…still.

I understand change is inevitable, but for a brief moment in the river of time, it was my home, my block, my community. I miss it so.