East Kong Yick

By Elana Lim

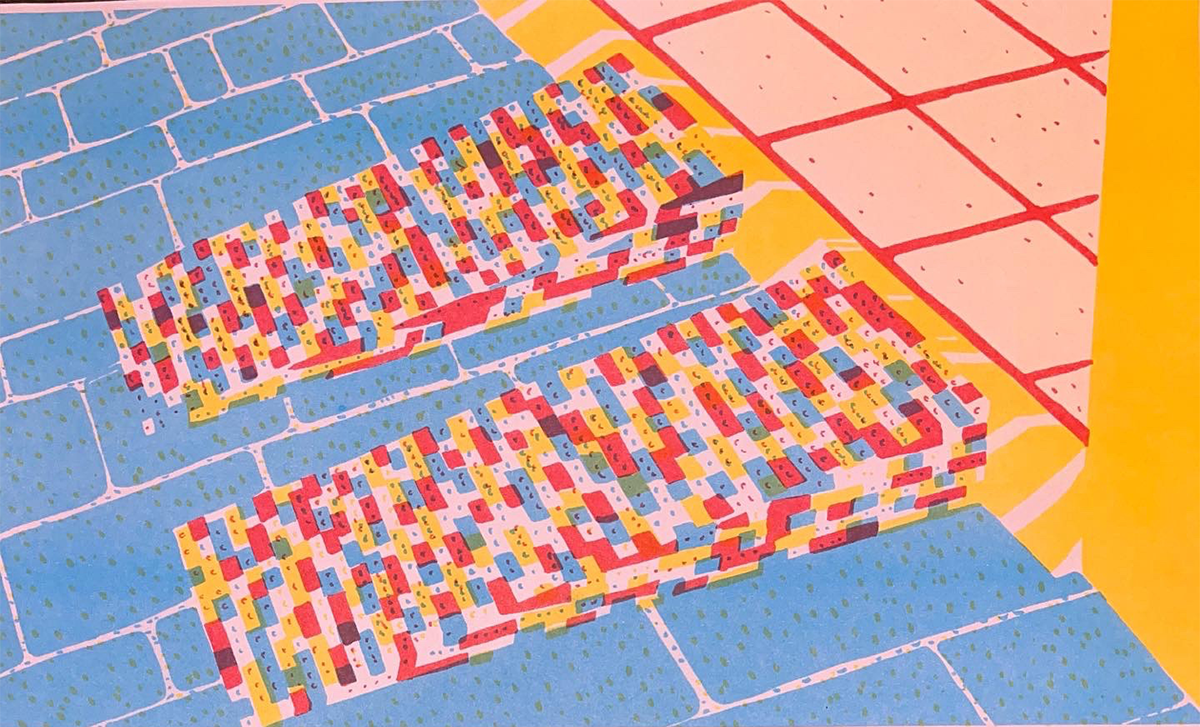

Twin four-story brick buildings, East and West Kong Yick, were opened as the center of a new Chinatown in 1910.[i] Back then, the 1889 Washington State Constitution forbade “aliens” to own property,[ii] but over 170 Chinese pioneering men found a way to work within state and federal laws.[iii] The Kong Yick buildings were born of the business acumen of a Chinese settler named Chun Ching Hock, who navigated the laws to start a mercantile store Wa Chong Company,[iv] and who acquired property to establish the first Chinese settlement in Seattle by 1871. In 1909 Wa Chong company purchased two parcels of land that had been granted to Seattle pioneer Doc Maynard and sold them to Kong Yick Investment Company which was incorporated in 1910 by merchant Goon Dip.[v] Those Chinese pioneers and over 170 Chinese stockholders created East and West Kong Yick.

For the past century, these structures have been home to several family associations, businesses, thousands of bachelors – Filipino, Japanese, and Chinese, hundreds of families, Chinatown emergency services, and gathering places for the elderly: Yee Goon – Woo family bachelors, Kay Ying Senior Center, and Luck Ngai Musical Club which still exists in West Kong Yick today. The East Kong Yick stands stronger than ever, reconstructed in 2008 as the new home of Wing Luke Museum, a National Heritage site, and safe haven for American Asian and Pacific Islanders to tell our history to 50,000 visitors a year from all around the world.[vi]

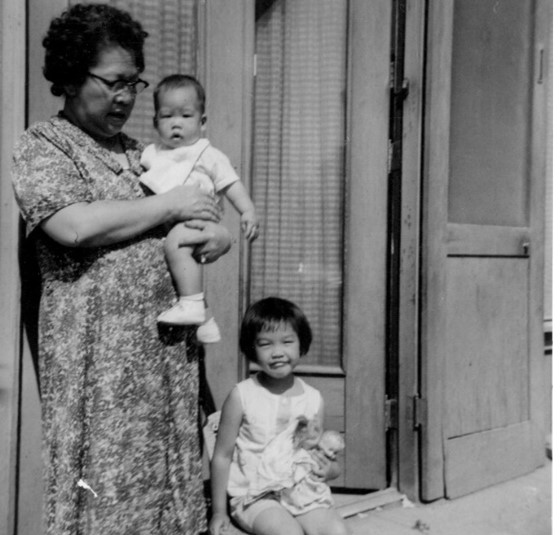

One of those 170 stockholders was Art Wing Eng who brought his wife Ou Shee in 1920. They are my grandparents and were one of hundreds of families who made their home in the Kong Yick buildings. They lived street level in East Kong Yick Apartment #507, around the corner from where my grandfather worked at Wa Chong Co.[vii] My grandmother Ou Shee gave birth to fifteen children in twenty years, eight of whom she raised in #507, including my father, Wallace. She also raised my brother and me there in the 1960s and 70s.[viii]

In 1941, Dad’s brothers Terrence and Bruce (Ou Shee’s 14th and 15th born) are standing on the front sidewalk of East Kong Yick, looking into a camera while my father (nicknamed Pudgy) shoots marbles. A typical day in their lives, but on December 7 that year, Emperor Hirohito of Japan commanded an attacked, bringing the U.S. into the war. A sinking feeling blanketed the Japanese community surrounding the Kong Yick buildings. “What will happen to us?” was a common refrain as told in oral histories recorded by Densho.org.[ix]

At the time the photo of my father and his brothers was taken, the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in force. By 1940, the Japanese community had grown to 5,770 people to fill labor demands because Exclusion shrunk the Chinese population to 1,781 people.[x] To protect its community, Chong Wa Benevolent Association handed out buttons saying “China,” a red and white pin that Pudgy put on his collar every day before he went to school. Some lent their buttons to Japanese friends so they could go downtown without being harassed. Some hid friends in the backseats of their “China” labeled cars to get them home safely after the 8 p.m. curfew for Japanese.

Then came Executive Order 9066[xi] and the public facing jargon: “evacuate,” “relocate,” to an “assembly center.”[xii] President Roosevelt called them: “concentration camps.”[xiii] Eventually 120,000 of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated, 80,000 of whom were American born citizens.[xiv] What does it mean to be an American citizen if a person’s ancestry is labeled a crime?

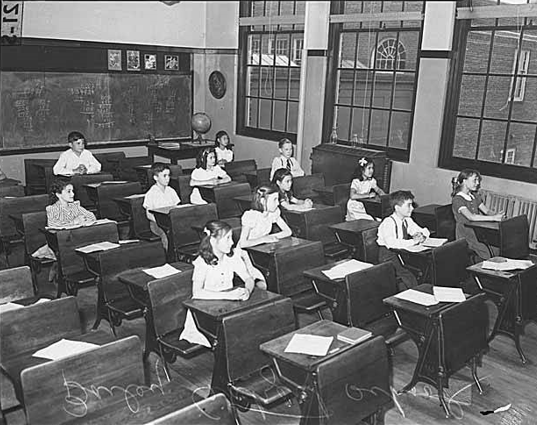

“There was a buzz at school,” Pudgy said, “but nobody knew where anyone was going or for how long.” That morning, he cut class from Bailey Gatzert School and went to Japantown where his friends were loaded into buses. Unable to get close enough to say goodbye because of armed guards, he could only wave. When he returned to school that day, “Half of the desks were empty,” he said. “I felt so helpless. Nobody could help my friends.”

Pudgy’s “China” button did not offset his fear as he made his way home through ghostly streets, past empty houses, apartments, and boarded-up storefronts, to the East Kong Yick, his place of safety.

After the war, few of the 5,000 Seattle Japanese returned.[xv] The Takita family who managed the Freeman Hotel in East Kong Yick did not return to run the hotel.[xvi] Chinatown and East and West Kong Yick’s presence became proportionally larger as Japantown shrank from seventy-two blocks in 1941 to six.[xvii]

When I was born twenty years later, my family was living at #507 with Grandma Ou Shee. I was her sole charge until I was four when my brother Chris was born. Little girl me was safe in Ou Shee’s East Kong Yick village – it did not have gates or watchtowers, but it protected all the same, as it did Ou Shee’s court of matriarchs. After shopping in Chinatown, the women, in wet wool coats in winter and bright pink lipstick and fluttery dresses in summer, stopped to visit. Some lived in the newly-friendly neighborhoods for “Oriental,” and “Negro, Jewish, Italian” people fresh from redlined blocks in the Central Area.[xviii] After finishing tea or coffee, the Chinese matriarchs waited for an adult child to drive them home or walk one block to the corner of Jackson Street to catch the #3 or #7 bus to Beacon Hill or Rainier Valley. Many had been widowed by husbands who had been ten, twenty, or thirty years older, and some were naturalized after the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act; others, like Ou Shee, never became citizens.

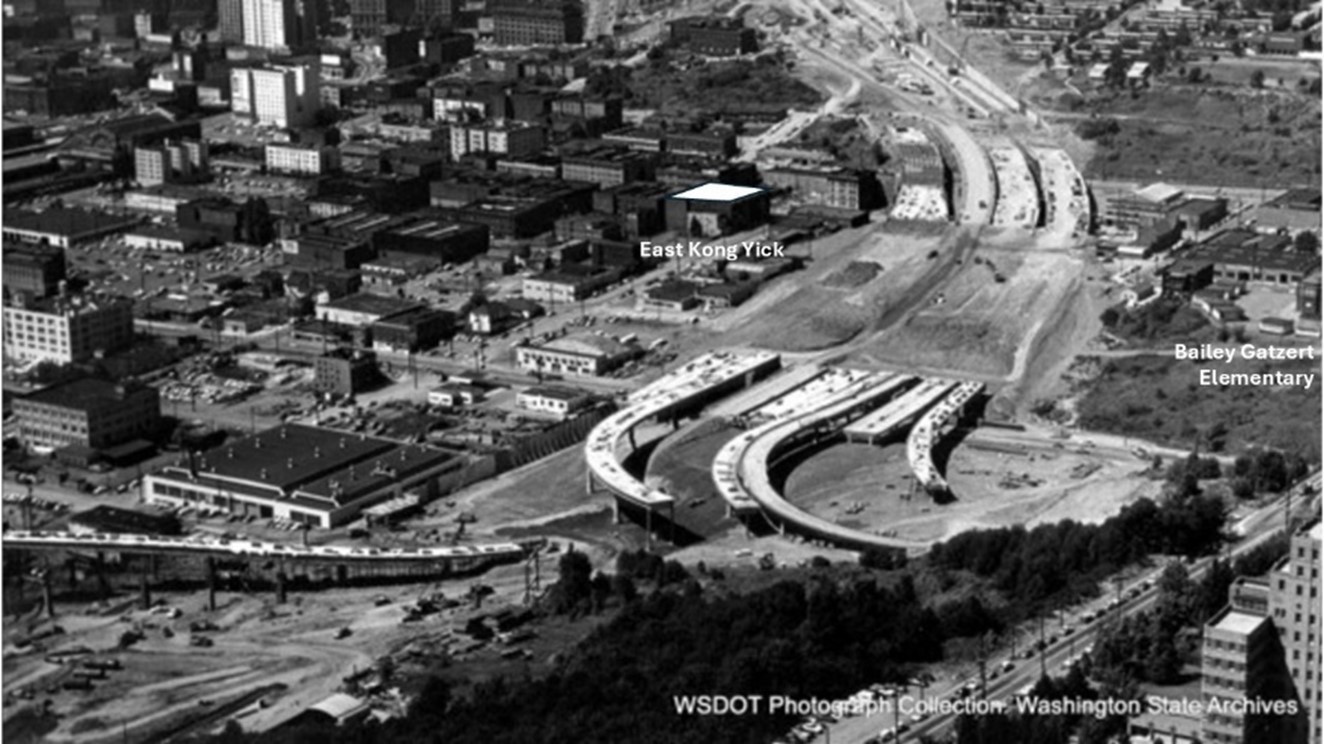

When I turned six, cars called Mustangs, Thunderbirds, and Falcons flew up and down the pristine cement of Interstate-5’s ten lanes. Construction of I-5 wiped out the eastern half of Chinatown ID (International District)[xix] and spared Tsue Chong, the noodle and fortune cookie factory in the freeway’s shadow across the street from East Kong Yick. On baking days, an aroma of vanilla wafted through the air, hot golden circles of thin dough were pulled from a vast oven and hand folded, inserting the “Confucius says…” slips before the cookies hardened. The smell of fresh baked cookies mingled with the stink of gritty exhaust and poisonous dust off I-5.

I was nine when I learned to abide by the rule to walk, not ride, my bike down the sidewalk in front of East Kong Yick, staying safe from speeding cars that veered off the Dearborn Street exit and roared along our block to Hospital Hill. I only rode my golden stingray, with its banana seat, in the Chong Wa playfield at the foot of East Kong Yick. Dad had found my two-wheeler for five-bucks in the “as-is” pile in the basement of Sears & Roebuck, now Starbucks HQ. He asked Uncle Ted Imanaka of 7th Avenue Service gas station to weld the broken bike together.

Grandma Ou Shee lived in East Kong Yick for 60-years until she died there in 1981. And for as long as I could remember, a woman named Nobi Kodama would sometimes attend our Eng family Christmas parties or visit #507. After being released from Camp Minidoka in Idaho, Nobi lived alone in a Chinatown hotel. When Grandma found out, she insisted that Nobi live with them. After her internment, Nobi was safe for several months in East Kong Yick apartment #507. Whenever she visited, I called her Auntie.

Before Pudgy died, the second and last time he talked of internment, he still believed that if such a disaster could happen to Japanese people born here, it could happen to anyone who looked like us. After my father died, I was haunted by an old newspaper photo, a Bailey Gatzert class, half-full of smiling children, and one lone Chinese child (I assume) in the back corner, all with their hands folded neatly on their desks; the other half: Poof.[xx]

When that class photo was taken in 1942, the 170 names of those men in the stock journal were kept in an iron-clad safe in West Kong Yick. Back then, people said Chinese and Japanese. I was seven when we began saying Japanese-American, Chinese-American, Asian-American, which was considered monumental a mere 56-years ago. Today, history is repeating. I love my father dearly, but I won’t repeat him. My button will say: American.

Afterword: I would like to acknowledge that we are on the unceded land and waters of the Coast Salish people, with the East and West Kong Yick located on the land of the Duwamish people. Other Coast Salish people have lived in this region for countless generations, including the Muckleshoot, Suquamish, Snoqualmie, and Tulalip. These people are the first Stewards of this land in which we work, live and build community, and I am grateful for their continuing presence. The East Kong Yick and Wing Luke Museum has been named a National Heritage Site. On May 8, 2024, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, of the Laguna Pueblo Tribe and 35th-generation New Mexican, launched the National Park Service “Home and Homelands,” a virtual exhibition that includes “under-told stories about women who have definitively shaped our nation.” Grandmother Ou Shee’s immigration interview is included.

Elana Eng Lim was born in 1961 and raised in Seattle’s Chinatown by her grandmother. After a career in Silicon Valley, and Microsoft, Elana raised her two boys with her husband, Randy. In 2017, as part of a museum community advisory committee, they helped curate a Wing Luke Museum exhibit, Apartment #507, part of the Historic Building Tour. In 2024, she co-authored Grandmother Ou Shee’s immigration interview, an article for the National Park Service “Home and Homelands,” a virtual exhibition that includes “under-told stories about women who have definitively shaped our nation,” presented by U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. Elana is writing a memoir of Chinatown, Tech, and her American life.

[i] The Wing Luke Museum is also a National Park Service-named area. National Park Service. “Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience” nps.gov, accessed September 20, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/places/wing-luke-museum-of-the-asian-pacific-american-experience.htm

[ii] Wong, Building Tradition, 157.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Wong, Building Tradition, 33, 56.

[v] Wong, Building Tradition, 156.

[vi] Email conversation with Cassie Chinn, Deputy Director, Wing Luke Museum, December 28, 2023.

[vii] A story of my grandfather Art Wing Eng can be found at Seattle Histories: My Grandfather’s Queue – Front Porch, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods.

[viii] A story of my grandmother Ou Shee can be found at Seattle Histories: My Grandmother’s Hand – Front Porch, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods.

[ix] Sharon Tanagi Aburano, interview by Tom Ikeda (primary); Megan Asaka (secondary), March 25, 2008, Densho.

[x] James Gregory, “Seattle’s Race and Segregation Story in Maps 1920-2020,” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, Seattle’s Race and Segregation Story in Maps 1920-2020 – Seattle Civil Rights, accessed November 28, 2024.

[xi] Brian Niiya. “Executive Order 9066,” Densho. Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Executive%20Order%209066 (accessed Nov 28 2024).

[xii] Do Words Matter? | Densho Encyclopedia. First accessed 1/5/2025.

[xiii] Euphemisms, Concentration Camps And The Japanese Internment : NPR Public Editor : NPR

[xiv] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. “Japanese American internment.” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 29, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Japanese-American-internment, accessed November 26, 2024.

[xv] Kristen Hayashi, PhD. “The Return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast in 1945” The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, The Return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast in 1945. Accessed November 26, 2024.

[xvi] Wong, Building Tradition, 205.

[xvii] Ðoan Diane Hoàng Dy, Senior Tour Manager, Wing Luke Museum Private Tour, January 14, 2024.

[xviii] Doug Honig, “Redlining, Racial Covenants, and Housing Discrimination in Seattle.” Historylink.org,Ocotber 29, 2021, https://historylink.org/File/21296.

[xix] Phil Doherty, “Interstate 5 is completed in Washington on May 14, 1969.” Historylink.org, May 10, 2010, https://historylink.org/File/9393.

[xx] “Bailey Gatzert School classroom after evacuation of Japanese Americans, Seattle, 1942. MOHAI Photograph collection, Image number PI25525.