Ou Shee Eng, her son Reverend Lincoln Eng in doorway, and Kai Goong (Godfather - seated), and her grandchildren. Circa 1954.

Ou Shee Eng, her son Reverend Lincoln Eng in doorway, and Kai Goong (Godfather - seated), and her grandchildren. Circa 1954. Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

My Grandmother’s Hand

by Elana Lim

In 2008, two grand openings led me to this story. First, the forty-year-old Wing Luke Asian Museum, affiliated with the Smithsonian and the only Pan-Asian American museum in the nation, reopened in its newly remodeled home in the East Kong Yick building in Seattle’s Chinatown, a four-story brick structure originally built in 1910 with investments from over 170 pioneering Chinese men. One of those men was my grandfather, Art Wing Eng, who, with my grandmother, Ou Shee, raised four sons and four daughters in apartment #507 on the ground floor of East Kong Yick. My grandfather died nine years before I was born. I lived there until I was ten.

The second opening was of a manila envelope curled in my mailbox, which contained forty-four pages. The cover letter, from the director of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration at the Department of Homeland Security, said that these papers, my grandmother Ou Shee’s file, had been released to me under the Freedom of Information Act. I would learn the details of Ou Shee’s immigration, not from her – she never talked about her emigration from China – but from these pages, documents that had been locked away for nearly one hundred years, first in Seattle and then in a warehouse in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, a place where she had never been.

On November 9, 1920, Art Wing and Ou Shee Eng sailed in steerage with 600 other passengers, separated from the 170 passengers in first and second class on the S.S. Empress of Japan, from Hong Kong. I imagine seeing them when they disembark at Vancouver, Ou Shee carrying her own bamboo suitcase down one gangplank and up another for the last leg of their journey to America. What did she make of the Princess Adelaide, a steamship with its 118 staterooms, hot and cold running water, heating, electric lamps, and glass windows? When she and my grandfather landed in Seattle on November 30, they were immediately separated, my grandmother was detained and held for twenty-four days, the standard protocol under the Chinese Exclusion Act.

When I was born to her son Pudge and his wife Mary in 1961, Ou Shee was sixty and stood a sturdy five feet tall. Her hair was black and slightly brittle from the chemicals that curled her naturally straight hair into a “permanent wave.” She wore wire-rimmed bifocals. Her smile sparkled, her perfect teeth pearly whites set in pink acrylic gums she cleansed in a glass of solution overnight. Make no mistake, with or without those magnificent teeth, Ou Shee was the matriarch of our family. Soft and round, her skin was loose under her chin. When she chuckled, her body jiggled.

As I read and reread the forty-four pages in the file written by strangers about the grandmother I had known so intimately, my fingers trembled. It was as if the typewritten words carried my grandmother’s breath and her tender voice – the girl Ou Shee had been becoming increasingly present. Nine pages had been withheld, replaced with sheets of paper, blank except for a code explaining that redactions were meant to protect the personal and official information of the subject and her immigration handler. I wondered what was left out and why such protections were still necessary one hundred years after the fact.

Two days after arriving, Ou Shee was diagnosed with “uncinariasis” also known as hookworm, and on December 2, her entry was rejected, but she was treated and retested over the next twenty-one days, probably because my grandfather Art agreed to pay for her board and medicine. Auntie Florence Chin Eng of Wa Sang grocery, who was related to my mother’s family, recalled her own medical experience in holding – they tested my “urine, and everything.”

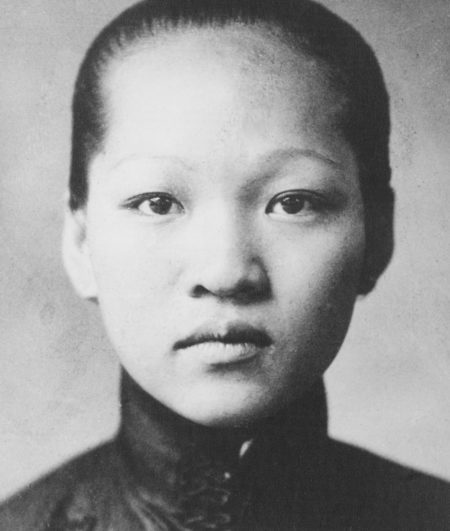

Included with Ou Shee’s Chinese responses to her interrogation is the English translation. The inspector, certainly a white man from the Special Board of Inquiry, described her as “20-years-old, 5’ 1”, double pierce both ears; brown spot right temple; large scar across forehead to left center; two brown spots right jaw.” The black and white immigration photo reveals the fresh bud of my grandmother as a young woman. Her hair is not styled in the tight curls I brushed as a child but pulled back slick against her head. A gradient shadow highlights a girlish prettiness I never knew. Her eyes penetrate as if she is staring down the photographer, and also me. She taught me that gaze when we played five-card stud: Gow gnan, she would say, poker face. I was raised on her gow gnan.

Imagine this young woman in an examination room, standing alone, wrapped in the captor’s gown, not understanding the language. Did the inspector see a person or a “chink”? Double pierce both ears, brown spot right temple are undetectable in the photo. How close did his eyes get to the large scar across forehead? Could she feel his breath? Were his fingers respectful, or did he manipulate her jaw as if he were assessing an animal at a county fair – two brown spots right jaw?

We’re in Chinatown, my grandmother’s hand gripping mine. “Lai shue. Gwua guy,” Hold my hand. Her hand is buzzing into mine. Cross the street. “Mo gong,” Don’t speak. “Nay henga ngoh? Look-yee.” Listen to me. Police, and we quickly cross the street. Policemen like these, loom over my class at Bailey Gatzert Elementary school, tell us their job is to protect us from bad guys. I want to believe them, but I don’t. As Ou Shee’s file mumbles at me, I understand her fear of the police. Just as the holding cell guards were not there to protect her, the police do not protect me. They are there to protect bawk gui white people from us. Who but an enemy gets locked up? How was five-foot-tall Ou Shee a threat?

As I read those single-spaced Xeroxes, tears on my cheeks: the grandmother I adored, the majestic woman who always protected me, reduced to courier type.

“What are your names?”

“Ow Shee,” is how the stenographer spells her answer.

She speaks in the Toisanese of her farmer family, of Chu Lin village in the Sun Woy district. “I am of the Ow family.” She was eighteen when her marriage was arranged, in the customary way, to a man twice her age. She is twenty now. There is an older brother who works a rice field in the village, her mother is alive and her father is dead. Ou Shee tells the interrogator that her husband is a widower, but I would learn, shhh, a family secret – Art’s first wife lived to be fifty-four, did not die until 1940 in the family village, twenty years after Ou Shee gave this answer to the interrogator. Did she know the truth?

On her wedding day, she was delivered by a “go-between” in a “sedan-chair” to Art’s house in Canton City. At the ceremony, done the “old Chinese way,” she meets her husband for the first time.

“How does it come that your husband, being quite Americanized, did not have the White man’s ceremony performed?” pressed the interrogator.

Rather than telling him that she preferred to marry wearing red, the color of celebration and good fortune, rather than white, the color of death and funerals, Ou Shee says “I don’t know,” an answer that will not offend.

“How much did this man pay your mother for you?” he then asks.

“Ngoh m’ai tui,” she answers again. I don’t know. These interviews took hours, and questions were repeated over and over to catch you in a trivial lie.

If I had been interviewing Ou Shee, I would have asked her the question I never learned the answer to: How did you come to read Chinese? The interrogator did not ask this. On the ship Manifest of Alien Passengers, she’d been labeled “illiterate”. And I have questions I would ask him: Was she allowed a trip to the bathroom, a glass of water? My grandmother had smoked since she was twelve, so she must have craved a cigarette, her head pounding from answering the same questions again and again.

“What is your object in coming to the United States?” the interviewer finally asked.

“Coming to live with my husband and keep house for him,” Ou Shee replied.

“The case seems regular in all respects,” the interviewer concluded, “with this exception, the applicant is possibly a concubine, the first wife having died, so it is claimed, some two years ago, in the home village, and Ark Wing marrying the applicant a few months later.” That assertion was consistent with the Page Act, the very first United States immigration law, signed in 1875 by President Ulysses S. Grant. The explanation was that all Chinese immigrant women must be “concubines”, a less offensive term, it was felt, than “prostitute.”

No wonder Art Wing’s first wife was a guarded family secret. When I learned about her, her split from Art sounded to me more like an amicable divorce: Art paid alimony, she sent one son to live with his father in America when he turned seventeen, and they shared family pictures with one another – her four children and Ou Shee’s eight. Art never again saw his first wife after he left her in 1920. Was Ou Shee a prostitute? No. A second wife? Yes.

After my grandfather Art Wing was interviewed and released, an unnamed Chinese witness still in holding, also recently arrived from Hong Kong, was questioned about conversations he’d overheard about Ou Shee. Identified only as the son of Chin Dip, the man said he’d heard Ou Shee referred to as a replacement wife, not a “plural wife.”

On Christmas Eve 1920, Art returned to First and Union Street to fetch Ou Shee who was scheduled to be released from detention. He had first to pay doctor’s and boarding fees, $33.92 ($463 in 2021) equal to one month of his salary; apparently, he spoke English well enough to easily make such transactions.

After the door of the immigration building shuts behind them, I see Ou Shee in Chinese clothes, following behind her husband along First Avenue, again carrying her bamboo suitcase. She takes in the alien sights and sounds of a trolley rolling down the track, Model T Fords rumbling along the brick-paved street, and gas streetlights, beneath them Christmas carolers singing. She does not understand the chatter of holiday travelers leaving the King Street train station. I so want someone to smile at her and wish her a Merry Christmas.

When she and Art stop outside the doors of the East Kong Yick, she looks back down the hill; the train station and the clock tower seem much further away than the four blocks she’s just climbed. I imagine she is excited but a little scared at being 6,000 miles away from the only home she’s ever known. From now on, she decides, she will look forward and not back – I know that about her.

I cannot emphasize enough that Grandma Ou Shee never spoke of her childhood, her history, or her journey to America with me or with anyone else. She kept her family secrets. She knew, for instance, that her husband, my grandfather, was a paper son because she could read Chinese.

, Art’s family surname, was Chinn, which I know only because Mom told me Dad’s family were the Chinns not the Engs, despite the fact that our surname was Eng.

Grandma lived her entire life within a bawk-gui white ghost world of dread and fear created by the Page and Chinese Exclusion Acts, even after their repeal decades later. Her children and other American Chinese adults of my parents’ generation still conceal family stories of expulsion, sudden imprisonment, bullying, everyday racism, and the identities of paper sons. “Live free but remember, not too free,” warned Auntie Jeni Kay Fung, not a blood relative but an Aunt by community relationship, when I told her in 2008 that I would someday write these stories.