Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

The Japanese Immigrant: The Documents in the Case

by Eleanor Boba

Please note that, in some cases, quotations used in this story include racist language.

A Century-Old Precedent

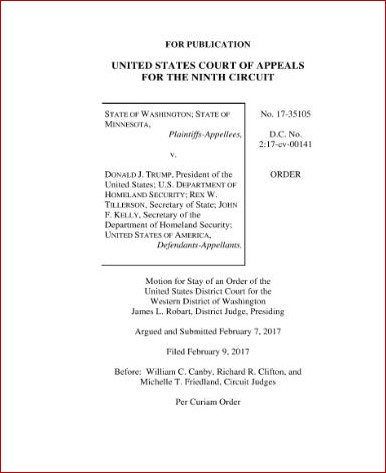

In 2017 the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals blocked an attempt by President Donald J. Trump to ban immigration from certain Muslim-majority countries. Among the case law cited was Yamataya v. Fisher (189 U.S. 86 1903), a case argued before the Supreme Court in 1903.

Also known as the Japanese Immigrant Case, Yamataya v. Fisher was an appeal by a Japanese immigrant to be allowed to remain in this country following a deportation ruling obtained by the immigration service in Seattle.

In this, I will tell the story of Kaoru Yamataya, the teenage girl at the center of the case, using documents and photos from archival sources. Kaoru’s story touches on immigration barriers, anti-Asian sentiment, the exploitation of women and girls, and the persistence of the Japanese community in Seattle in rallying to her cause and providing funding for her legal appeals. This project also illustrates the difficulties in researching events of over 100 years ago, including the need to assess the validity of primary source materials that often reflect the biases of the times.

Kaoru’s story

On July 11, 1901, Kaoru and Masataro Yamataya, Japanese nationals, disembarked from the ship SS Kaga Maru at Smith’s Cove in Seattle. The pair were allowed to leave and headed to a boarding house in Seattle’s Japanese district, Nihonmachi, where five days later they were arrested by an official, Chinese Immigration Inspector Thomas Fisher.

The immigration authorities held a brief hearing (at the Board of Special Inquiry) and then asked for an order of deportation for Kaoru from the office of the Secretary of the Treasury. By July 23, the order was in hand. The immigration service had decided that the girl met the criteria for deportation outlined in both the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Immigration Act of 1891: she was a pauper and likely to become a public charge. The man who accompanied her, who claimed to be her uncle and adoptive father, was charged with importing a woman for prostitution. Kaoru was 15 and pregnant. Masataro was 34.

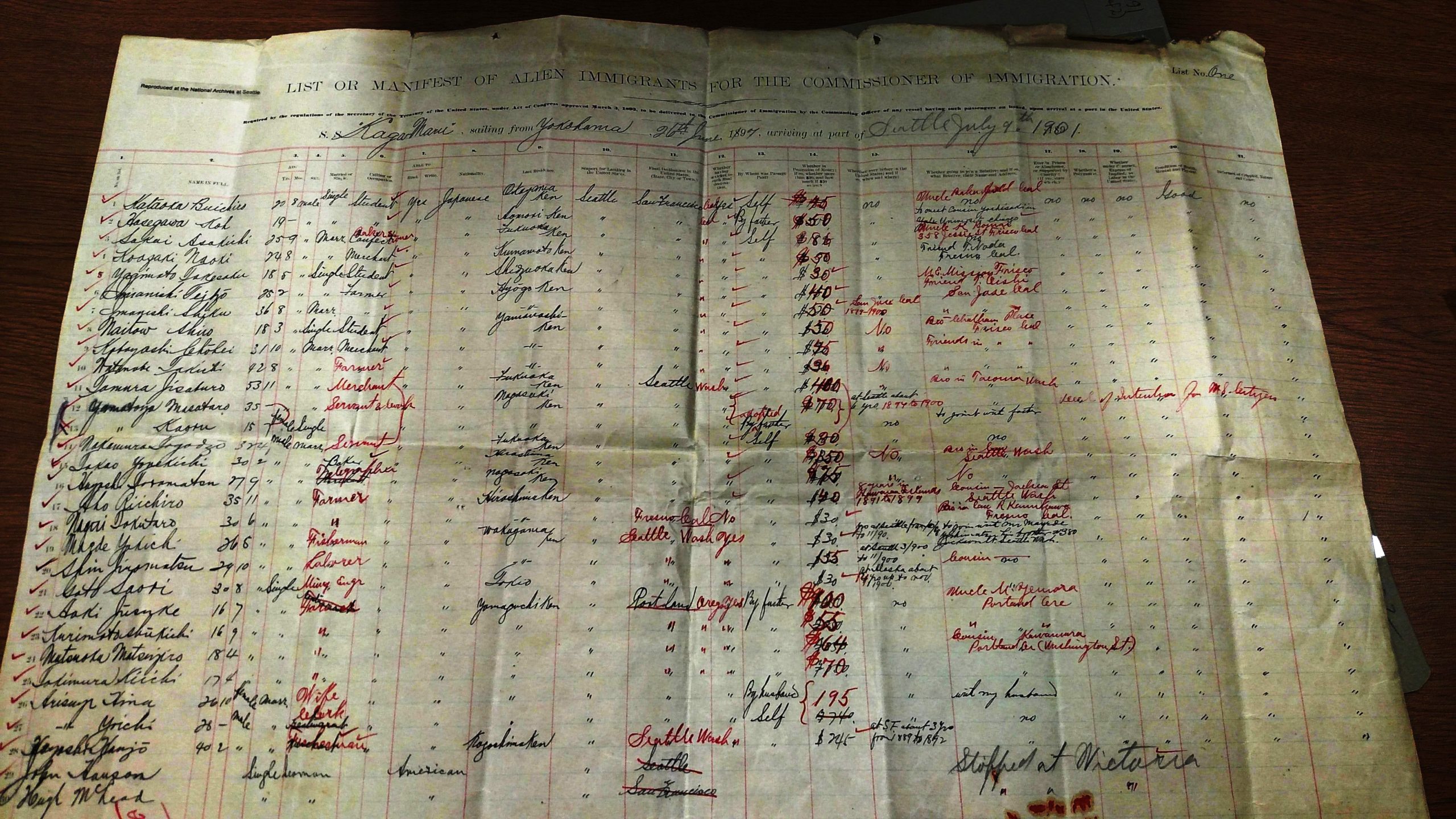

Arrival in Seattle: July 11, 1901

The passenger manifest of the Kaga Maru lists Masataro and Kaoru Yamataya. Masataro’s occupation is listed as “servant” and, possibly, “cook.” In the space asking whether the passenger is going to join relatives is written “to join with father.” Kaoru appears to be one of only two female passengers; the other is listed as “wife.”

Landing

The record of Kaoru’s arrival in Seattle gives only limited information: her age (15), her race (“Jap”), and in the space labeled “Destination and Name and Address of Relative or Friend to Join There” is listed “None” and “Settler, Seattle, Wash.” The ship’s name is noted as the SS Kaga Maru.

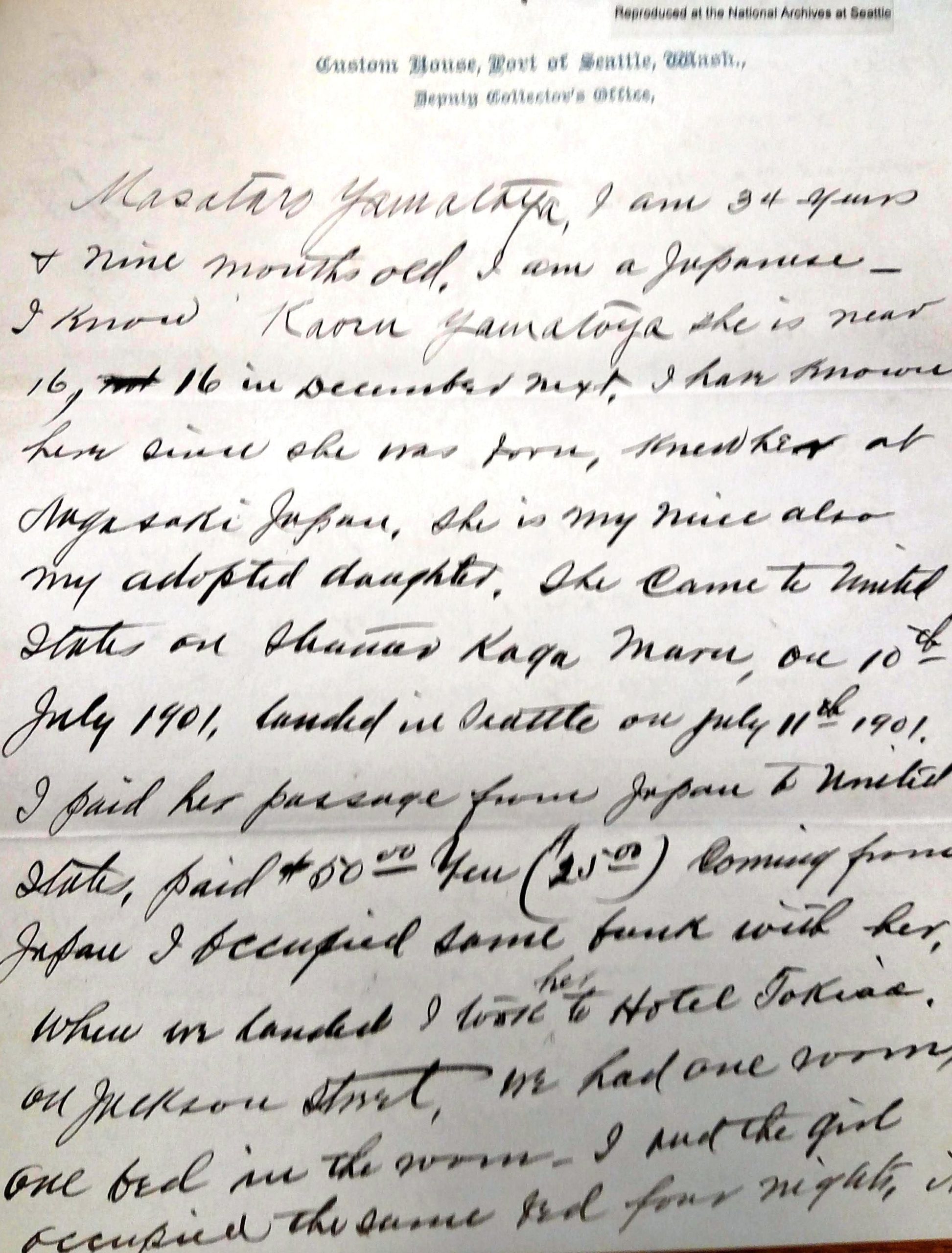

Masataro’s Statement

Upon their initial arrest by Inspector Fisher, Koaru and Masataro provided statements. The signed accounts were highly personal and incriminating and, of course, were used against them in a court of law.

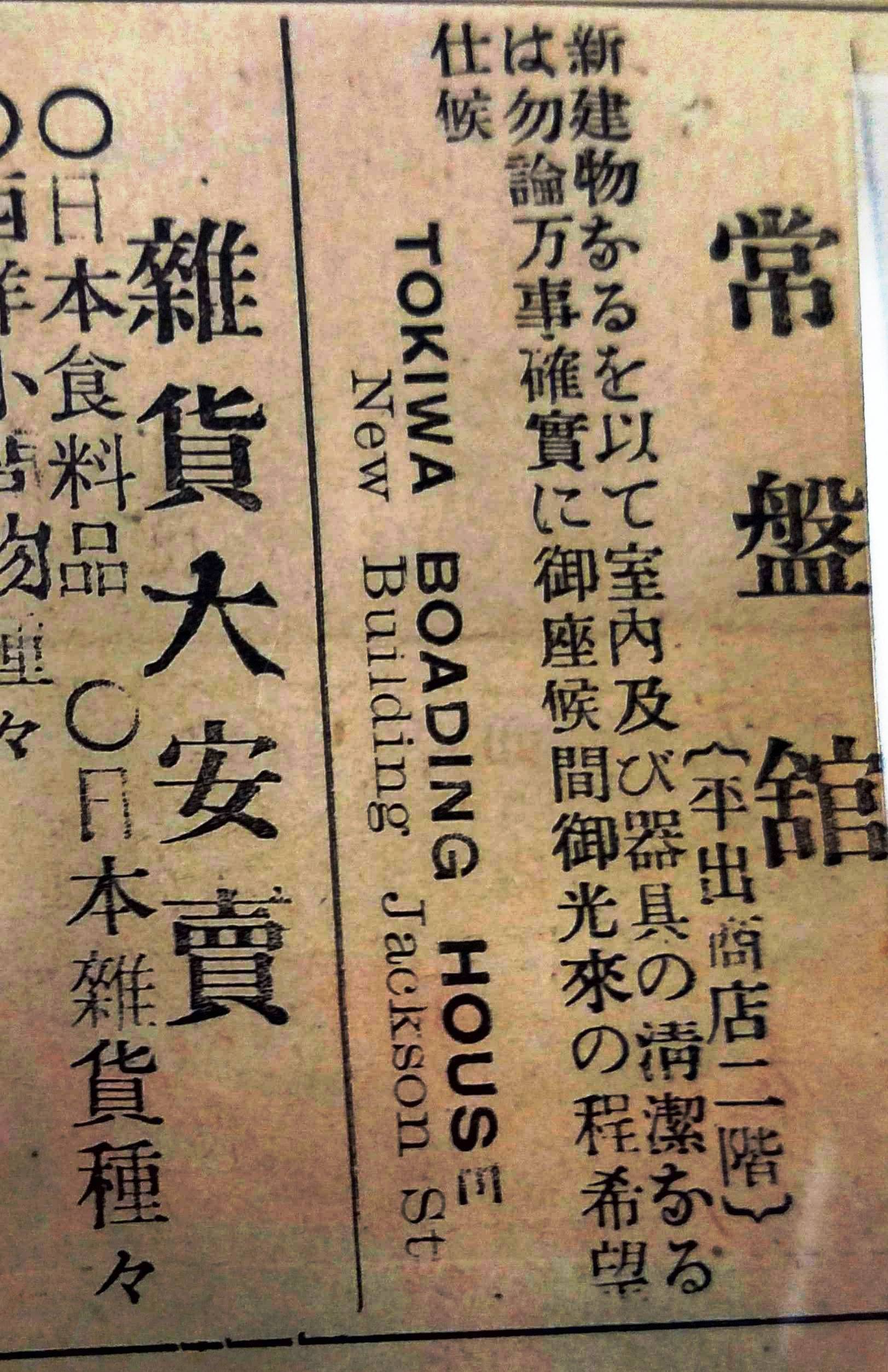

Masataro admitted that he had paid Kaoru’s passage to the States, that he had shared a bed with her at the Tokiwa boarding house, and that he had a wife in Spokane who did “immoral business.” The statement goes to say he has very little money and no place to take Kaoru; that she has a little money from her father and that he plans to place her at the Japanese YMCA in Seattle.

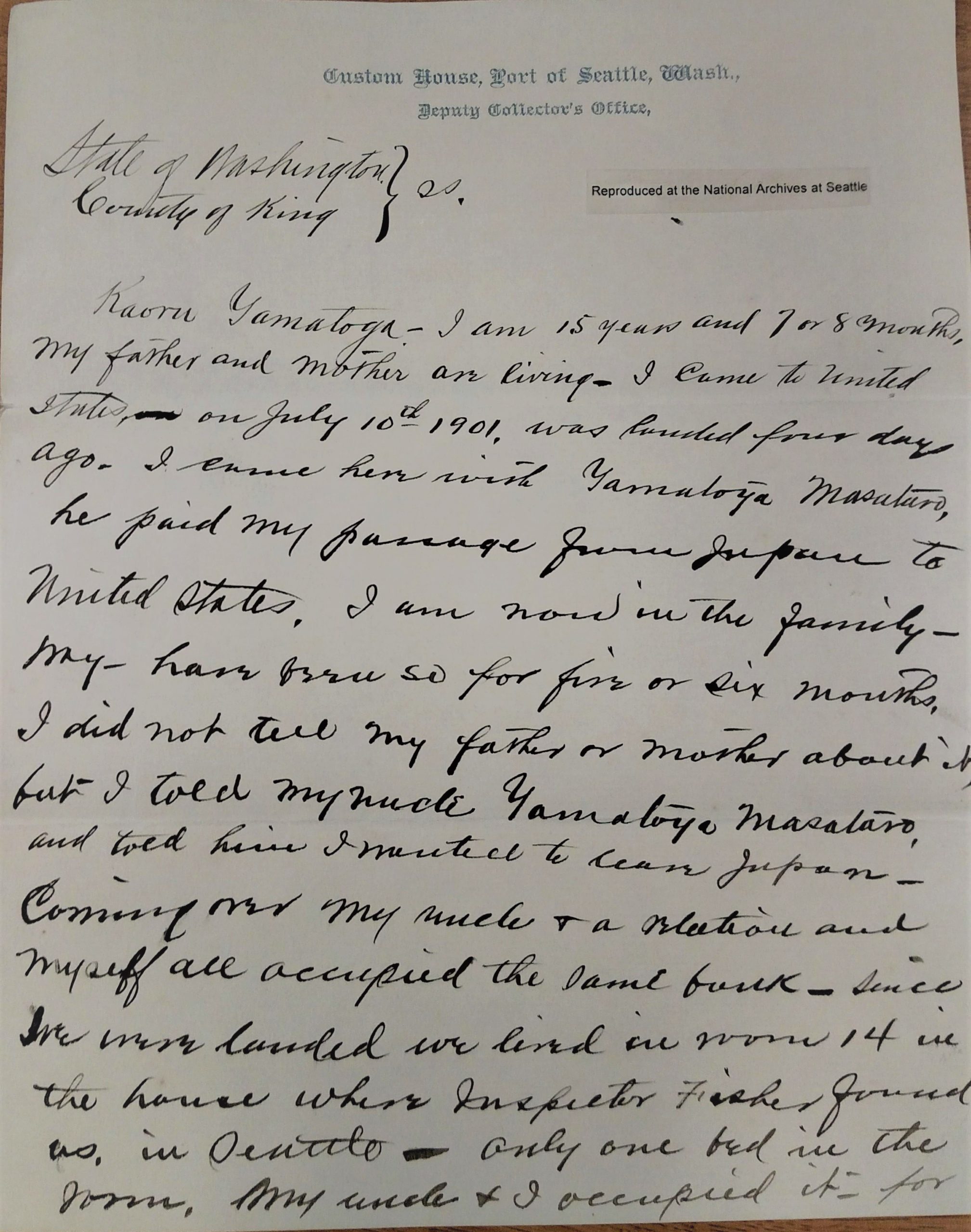

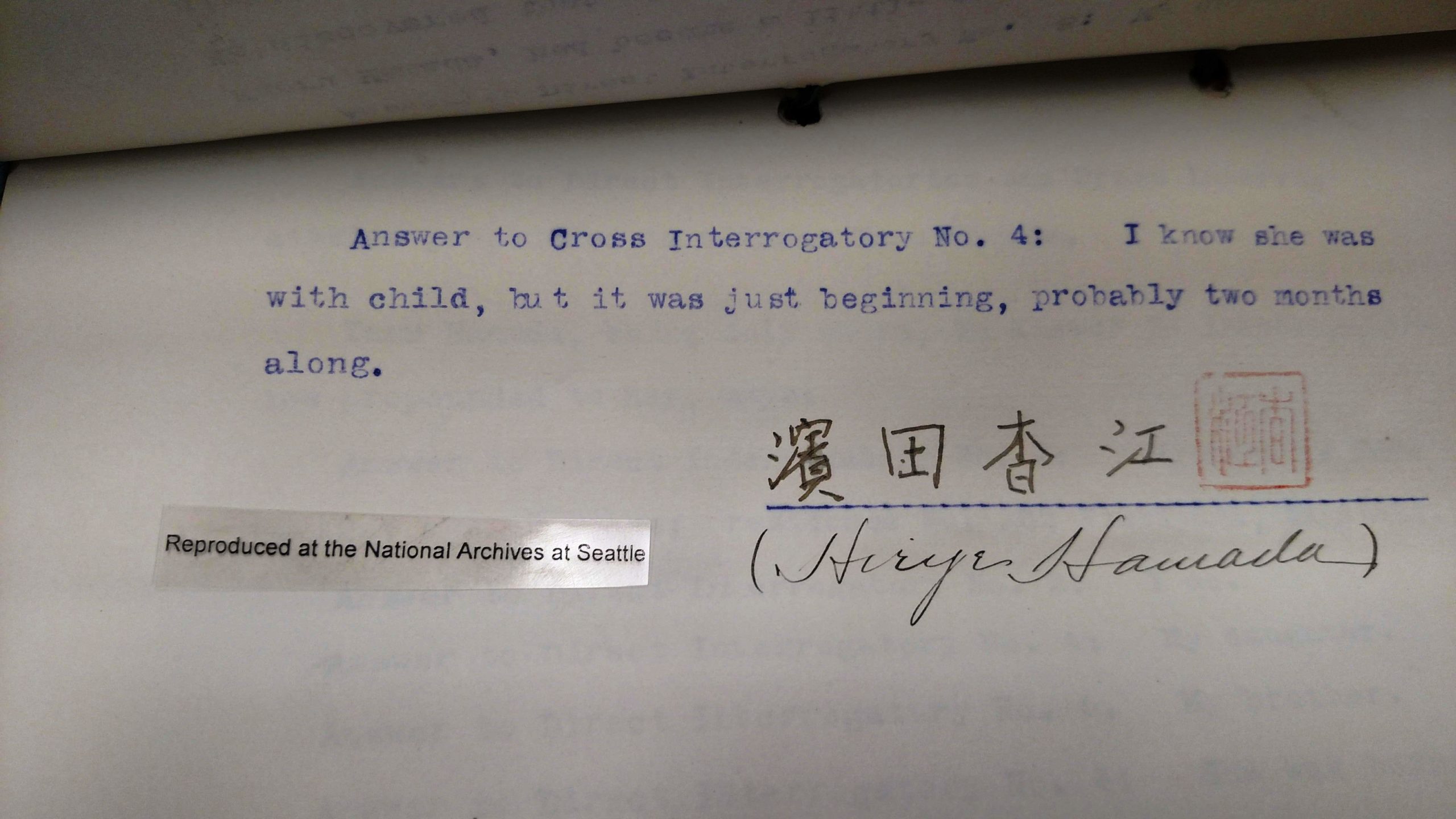

Kaoru’s Statement

Immigration officials were on the watch for evidence of women and girls being imported for prostitution, a common problem.

Kaoru’s statement echoes that of Masataro’s – that he paid for her voyage; that she shared a bunk with him and with another relation. The document goes on to say that she is in the “family way” and has no money – “had none when I came here.”

Kaoru spoke no English and the statement, obtained through a translator and written out in the hand of Inspector Fisher, must be taken with a large grain of salt.

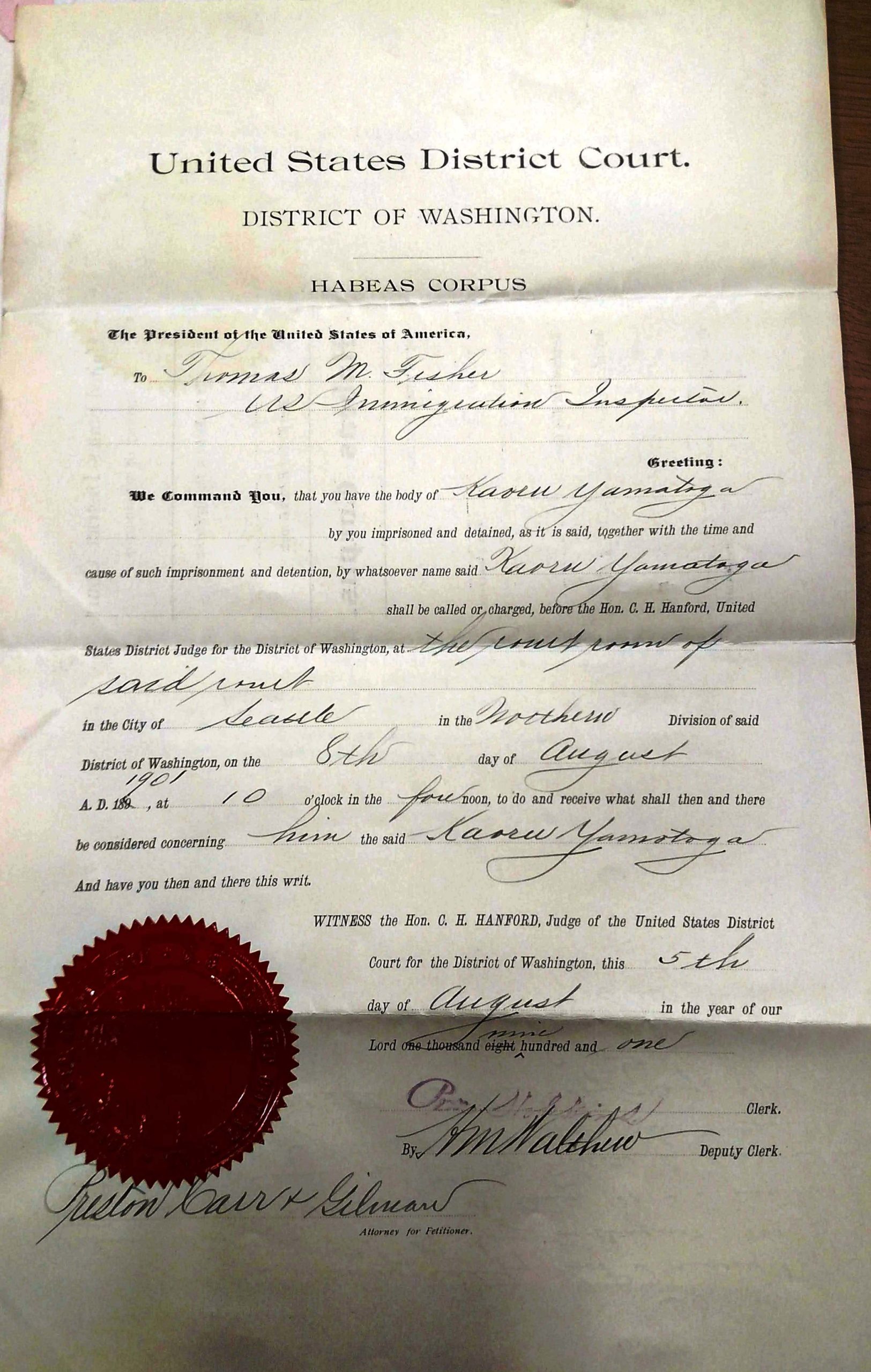

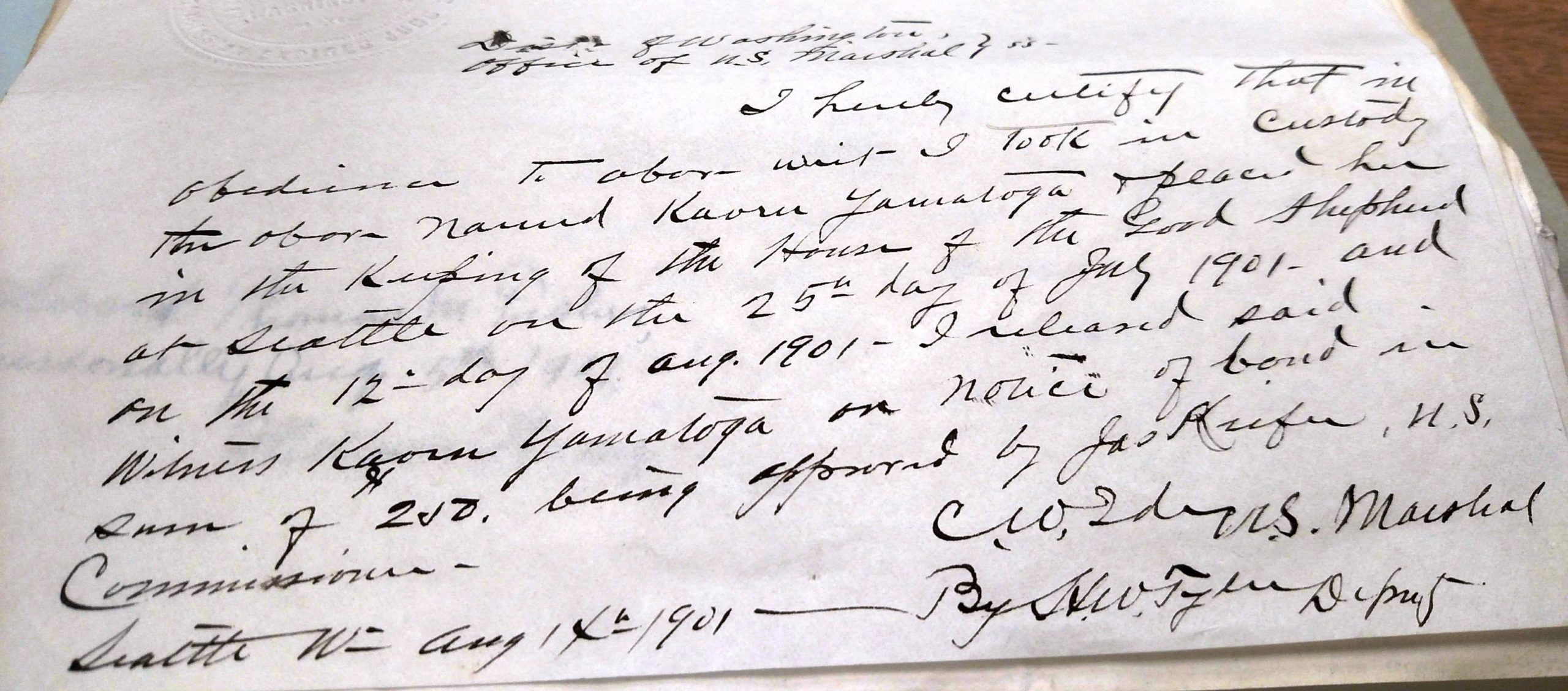

Habeas Corpus

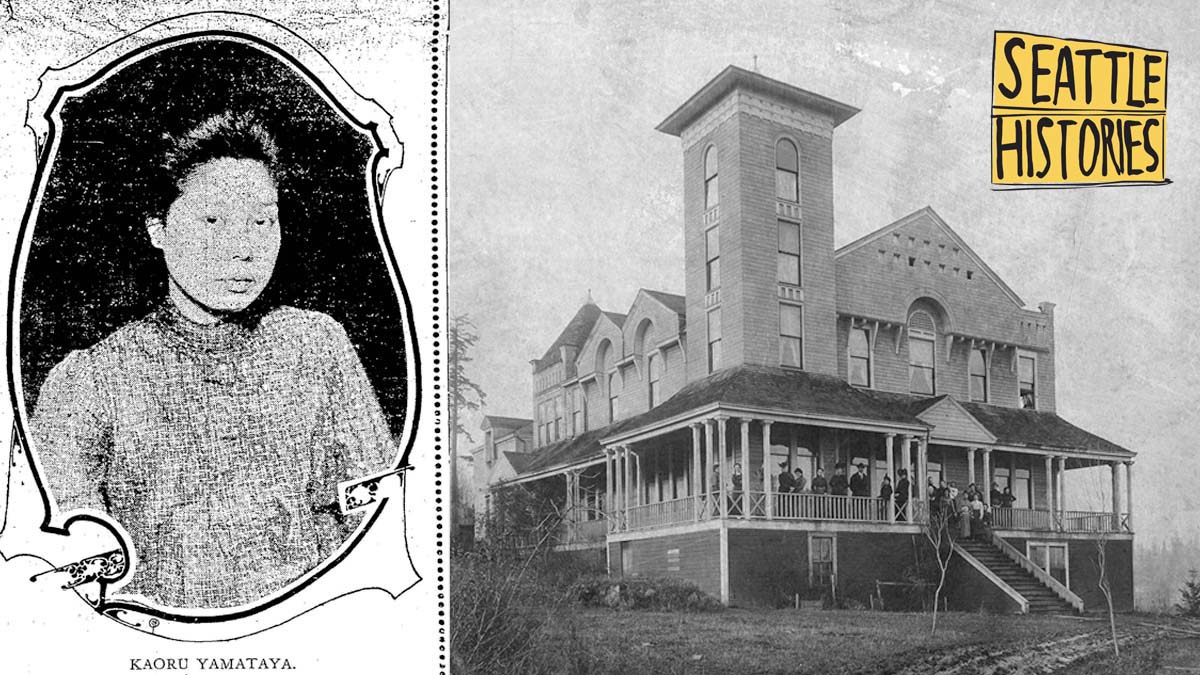

While they waited for the order of deportation to arrive, authorities had Kaoru placed in a home for troubled girls and “fallen women.” The move was justified by naming her a witness in their case against Masataro.

Kaoru and Masataro may not have known anyone in Seattle, but they still had friends. When they were arrested and deportation proceedings were underway, the Japanese community rallied to their cause. Several Japanese men and a couple of Americans provided “sureties” or bail bonds guaranteeing that Kaoru would appear as a witness in the case against Masataro if needed.

The standard procedure when fighting an order of detention and deportation was to file a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. White lawyers hired by the Japanese community did just that, asserting that Kaoru was “not an idiot or an insane person; that she is not a pauper, and is not likely to become a public charge; that she is not suffering from any loathsome disease or any disease…that she has not been convicted of a felony or other infamous crime or misdemeanor involving moral turpitude…”

Kaoru at the Crittenton Home

Kaoru stands on the steps of the Florence Crittenton Home in the Rainier Valley about 1901. The newly founded charity offered shelter to unmarried pregnant women and girls.

Kaoru was court-remanded to the care of the home shortly after arriving, thus fulfilling the prophecy that she would become a “public charge.”

Baby Thomas

Two and a half months after arriving on these shores, Kaoru gave birth to a son at the Crittenton Home on September 24, 1901; the infant died two months later of pneumonia. His death notice was submitted by Dr. Harriet J. Clark, the physician who provided services to the Crittenton Home. The child was named Thomas. Wild speculation might lead one to suppose that Kaoru chose the only English name she knew, that of Immigration Inspector Thomas M. Fisher.

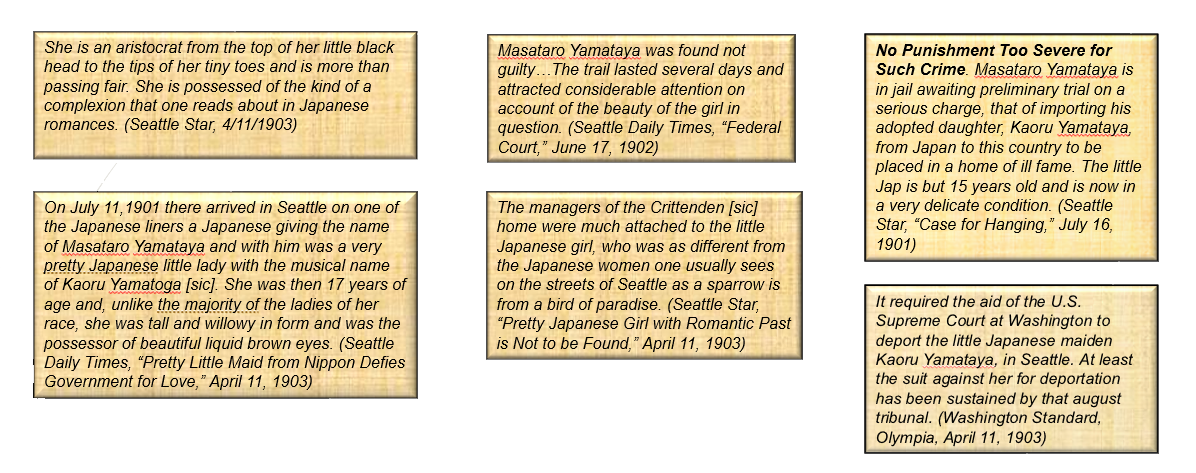

Kaoru in the Spotlight

Newspapers of the day were quick to dote on Kaoru, while at the same time condemning Masataro even before he was tried. Sentimentality and romanticism vied with moral outrage, often expressed in unabashedly racist and demeaning terms. Embellishments to the story were fair game.

“Pretty Japanese Girl”

The Seattle Daily Times printed the photo at left, likely a studio portrait from Japan taken as part of Kaoru’s travel documents. The grainy photo at right, printed by the Seattle Star shows a woman in western dress. The writer doubts that this is truly Kaoru.

The Case Against Masataro: Support from Home

Masataro Yamataya was put on trial in federal court in Seattle on June 13, 1902, on charges of bringing a woman into the country for immoral purposes. Four days later he was acquitted.

His lawyers had been able to obtain depositions from Kaoru’s family in Japan, sworn before the United States Consul in Nagasaki, Charles B. Harris. Her father and brothers each testified that Kaoru had gone with Masataro, her uncle, at their request, to get her away from her lover, and to give her a fresh start in America.

The Case Against Kaoru: The Wheels of Justice

In coming to America without a husband, job, or prospects, Kaoru ran up against decades of restrictive federal immigration law compounded by anti-immigrant and anti-Asian sentiment. For reasons that are not entirely clear, voices in the Japanese community in Seattle took up her cause, raising funds for a legal defense and hiring a team of American lawyers.

Meanwhile, immigration officials, led by Inspector Fisher, pushed forward with efforts to detain and ultimately deport her. Although their case against Masataro, alleging that Kaoru was a prostitute, had fallen apart, they continued to assert that Kaoru was a pauper and likely to become a public charge.

From the initial writ of habeas corpus, a slew of legal actions flew back and forth between the opposing sides, summarized in this legal word salad in the government’s brief to the Supreme Court:

“I respectfully submit that the order of the court below in favor of the Government, overruling the motion to quash the return to the writ, and sustaining the demurrer to the traverse to the return, should be affirmed.”

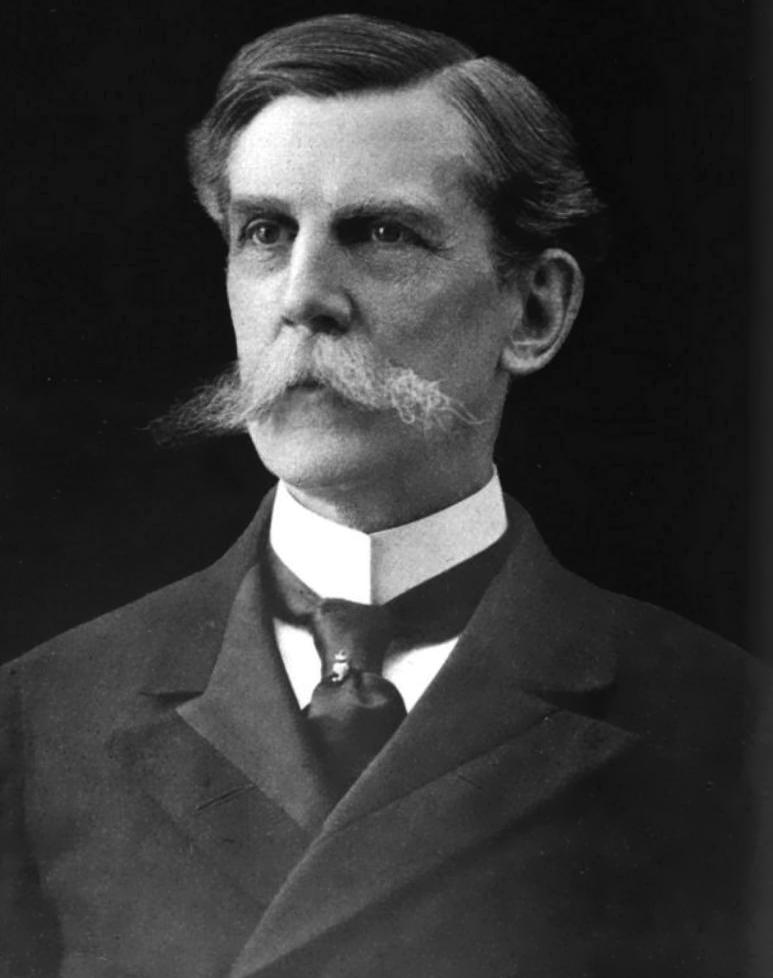

Henry M. Hoyt, Assistant Attorney General

The Supreme Court Decides: “Her Misfortune”

Early in 1903, the case reached the United States Supreme Court.

The court’s ruling in Yamataya v. Fisher was handed down on April 6, 1903. The decision by the justices was bad news for Kaoru — she was to be deported — but also contained a grain of hope for future immigrant cases.

Kaoru’s lawyers had challenged the constitutionality of the Immigration Act of 1891 which had given immigration officials broad latitude to deport aliens. They argued that Kaoru had been denied due process, that she had been falsely imprisoned, denied counsel, and that, speaking no English, she could not understand the proceedings being carried out against her. They accused Inspector Fisher of abuse of power in his questioning of Kaoru and Masataro, proclaiming him “prosecutor, judge and jury.”

Ultimately, the court sided with the government. The jurists stated that the law against paupers, such as Kaoru was deemed to be, was “designed to protect the general public against contact with dangerous or improper persons.” As for the language barrier: “If the appellant’s want of knowledge of the English language put her at some disadvantage…that was her misfortune.” The court’s decision was seven to two.

Kaoru a Fugitive: From Pillar to Post

Upon their initial arrest in 1901, Kaoru and Masataro were separated – he sent to jail and she to a “home.” At first she was placed at the House of the Good Shepherd, a Catholic charity for troubled girls, at that time on Seattle’s First Hill. She was briefly released from confinement when the writ of habeas corpus was granted. During these two weeks her whereabouts are unknown. Rumor had it that she was tracked down to Salt Lake City by US Marshals who then placed her at the Crittenton Home in the Dunlap neighborhood of the Rainier Valley. Both homes made convenient dumping grounds for women and girls who could not be accommodated in the county jail. After giving birth to – and losing – her son, it appears that Kaoru remained in the charge of the Crittenton Home. However, when news of the Supreme Court’s decision was received, she had disappeared. Newspapers reported that she was “spirited away” and was on the run for several years before being located at a boarding house in Portland, Oregon.

Kaoru Found – and Lost

As of October 1906, Kaoru was in King County jail; two weeks later she was deported on the steamer Shinano Maru bound for Yokohama. She was approximately 20 years old by this time.

Due Process Affirmed

As mentioned above, Yamataya v. Fisher did provide a consolation prize for immigrant advocates. The high court affirmed the right to due process — in a way:

“This court has never held, nor must we now be understood as holding, that administrative officers, when executing the provisions of a statute involving the liberty of persons, may disregard the fundamental principles that inhere in ‘due process of law’ as understood at the time of the adoption of the Constitution.”

This is the sentence cited in State of Washington; State of Minnesota v. Donald J. Trump (et al), filed February 9, 2017, in response to Trump’s first Muslim ban.

For Kaoru it was too late; the court adjudged that she had been granted due process in her initial hearing before the immigration tribunal in Seattle.

Context: The Japanese Viewpoint

We are left with questions: why did immigration authorities pursue Kaoru for five years expending considerable resources in the effort? Why did the Japanese community rally to her cause and commit what must have also been considerable funds to fight all the way to the Supreme Court?

Although exact motivations cannot be fathomed at this distance, it seems likely that the Japanese saw her predicament as a chance to challenge the validity of the 1891 Immigration Act. Japanese leaders and journalists in the United States were vigilant about their rights as immigrants, landholders, and proud Americans, if not citizens. Although very few issues of Seattle-based Japanese language newspapers from the day are extant, we can glean something from editorials printed in English in the American shinbun of the early 20th century.

A common theme in these editorials is the call for fair and equal treatment.

“So long as we are treated on an equal footing with other immigrants in general, we have no complaint to make. All we ask for is a fair, just and equal treatment.”

Nichibei Shinbun (San Francisco), December 12, 1922.

“We demand a universal stand of regulating immigration with equal justice to every nation, but that universal standard, it must be remembered, goes with an universal standard of citizenship. No person should be denied access to naturalization.”

Nichibei Shinbun (San Francisco), April 5, 1914.

“The Japanese immigration problem is all too frequently used as a political tool by unscrupulous politicians. And those not well informed on this subject are driven about by selfish capitalists who preach propaganda to suit themselves.”

Nippu Jiji (Honolulu), June 10, 1920.

From Restriction to Exclusion

Another theme found in Japanese American newspapers is patriotism. Loyalty to America despite discrimination is often highlighted. This idea was sorely tested when the 1924 Immigration Act effectively banned all immigration from Japan.

Those who know them [Japanese] best freely testify that their patriotism is not confined to their own country, but extends to the one whichin they reside, even though denied the privilege of citizenship.”

Nichibei Shinbun (San Francisco), July 4, 1905.

“…the Japanese exclusion problem is of paramount importance in the shaping of future intercourse between Japan and America…The enaction of an exclusion law against the Japanese people would constitute an open discrimination which needless to say would widen the breach between the Pacific, more so than by the mere separation of water…any discriminatory legislation [disregarding] the sensibilities of the Japanese nation cannot but be construed as stigmatizing the Japanese people as an inferior race of people…”

Nichibei Jiho (New York), April 26, 1924.

Conclusion

Since 1903, Yamataya v. Fisher has been cited more than 300 times in court actions. As part of case law, it is studied in law schools. In 2017, the provision for due process became a key argument in the fight against Donald Trump’s Muslim ban. The suit filed by the states of Washington and Minnesota was challenged and argued before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which refused to stay (halt) the temporary restraining order imposed by James Robart, U.S. District Court judge for the Western District of Washington, a few days earlier. The court actions forced the Trump Administration to delay, revise, and narrow its immigration strategies.

Immigration continues to be a highly contentious topic in the politics of this nation.

Further Reading

Sources for this presentation include the court proceedings in the case Yamataya v. Fisher retrieved via Google Books; the immigration and federal court records of Kaoru Yamataya and Masataro Yamataya, National Archives and Records Administration; Ancestry.com; the newspaper archive of the Seattle Public Library; the Rainier Valley Historical Society; and the Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library and Archive, Stanford University.

For a more detailed discussion of some of these issues, see

- Eleanor Boba, “The Supreme Court Rules in the Japanese Immigrant Case, Yamataya v. Fisher, on April 6, 1903,” HistoryLink.org, https://www.historylink.org/File/20597.

- Eleanor Boba and Nancy Dulaney, “Mutual Benefit: the Girls and Women of the Seattle Crittenton Home,” https://remnantsofourpast.blogspot.com/2020/11/mutual-benefit-girls-and-women-of.html.

- David A. Takami, Divided Destiny: A History of Japanese Americans in Seattle, 1998.