Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

Teacher Tale – Von

By Betty Lau

Reader Notes: Names of students have been changed to protect their privacy. The spelling of Laotian words provided by Von. Seattle Central Community College is today’s Seattle Central College. ESL is today’s English Learner (EL) or English Language Learner (ELL) or multilingual students. All but three photos were taken by Betty Lau.

Grading papers in late September 1994, I heard the heavy classroom door being yanked open, then a familiar, cheery voice called out, “Ms. Lau, you have a new student!” I rose from my chair with some surprise as they approached my desk. Next to Ms. Zarelli, the school counselor, stood a youth of about 5’6”, medium build, shaved head, dressed in the orange robes of Buddhism, and for Seattle’s mild fall weather, socks on sandaled feet. He glanced about warily, taking in my small classroom’s décor: a kanga cloth emblazoned with Karibuni, meaning Welcome, a red wall clock numbered in Chinese, a world map, news articles on cultures of the world, posters, and three bookcases overflowing with books.

“Ms. Lau, this is, uh….” his name escaped her, but she brashly forged ahead, blurting, “How do you say your name again?”

A hasty, multi-syllabic name tumbled from his lips.

“Well, P-p-p-,” said Ms. Zarelli, stumbling over the pronunciation, “this is Ms. Lau, your ESL Humanities teacher. She’ll take good care of you.”

Smiling, I extended my right hand, “Welcome to Middle College!”

He tucked both hands into the folds of his robe, uttering a well-practiced, “Sorry, I no shake you hand. No touch woman. I am a monk.”

Ms. Zarelli ebulliently exclaimed, “Well, I’ll just let you two get acquainted while I get back to work!” And then she handed me his school file and whooshed out the door.

I asked the youth, called Von, to say his name a few more times for me to practice and learn.

“Von, please have a seat, and let’s talk.”

So began my friendship with a most unusual student in a most unusual school, Middle College High School (MCHS) at Seattle Central Community College (SCCC).

Founded in 1990 by Seattle Schools Deputy Superintendent of Curriculum & Instruction Dr. Alice Houston and staffed by just six teachers with a few support staff, MCHS specialized in recapturing school dropouts by offering high school completion combined with a transition into SCCC classes and programs. To qualify for Middle College, a youth had to be 16 or older and meet one of the following criteria: out of school for at least a year, have a probation officer, or choose between “Go to school or go to jail.” Invariably, going to school was preferred as the lesser of two evils.

Odd qualifications, but they were necessary to avoid accusations of “poaching” students from other high schools. Students equal funding; the more students, the more funding.

The Middle College concept was ingenious: enticing street youths back to school with college collaboration, intensive support, overwhelming “can’t miss” opportunities for college credit, internships, and career exploration just steps away. Their campus? A high school tucked into a community college, where they would be surrounded by students their own ages but who were actual college students, who would, hopefully, be positive influences on academics and behaviors.

I mentally reviewed the qualifiers for our school, trying to imagine how a young Buddhist monk could fit any of them. Skimming through his file, I saw he had earned some credits toward graduation.

“Von,” I asked, “Why didn’t you stay at your other school?”

“The other student, they very bad, laugh. Pull my robe. Pat my head. Call me bad word. Every day. No go school, stay in temple better.”

He qualified for Middle College based on a refusal to attend school, which was the result of ongoing harassment and breaking of a cultural taboo—touching his head. No wonder he wouldn’t attend! In the Laotian culture, only parents or medical personnel are allowed to touch an individual’s head, which is believed to be the seat of one’s spirituality.

He readily shared how the older monks had ordered him back to school, but he steadfastly refused. The Abbot counseled patience and forgiveness. Von was willing to forgive–he just couldn’t face the daily onslaught of bullying.

Abbot Khampuey insisted: He needed someone to learn English in order to conduct temple business in an English-speaking society. That’s why he had specifically requested a young monk for their order. They needed at least one of their number to take care of temple bills, tax reports, and general correspondence. They also needed someone to interact with the police, fire department inspectors, doctors and dentists, contractors, and the growing numbers of US-born generations of English-speaking congregants.

In desperation, the Abbot took Von back to Bilingual Enrollment and found out about Middle College. Perhaps he would thrive in its much smaller student body. Von agreed to give high school another chance.

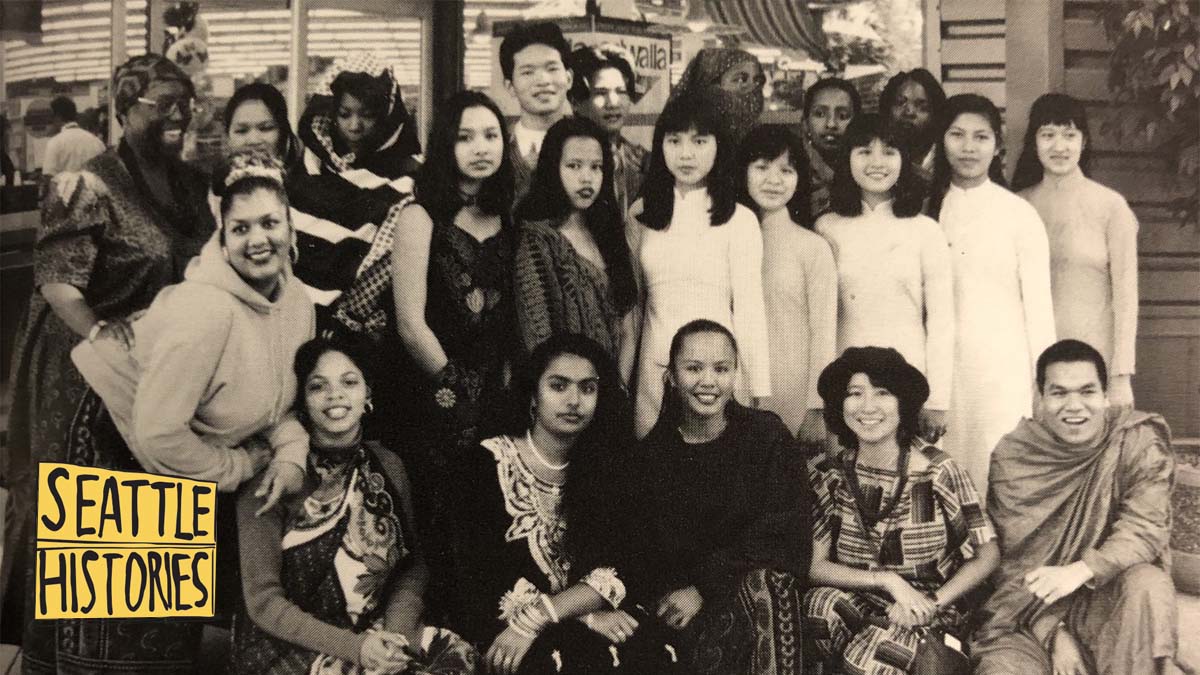

At first, I mildly worried about him. How he would fit in? Our student body was quite small, numbering about 170, the majority students of color, with a sprinkling of openly LGBTQ+ youth. How would they react to a Buddhist monk in their midst?

Despite their myriad learning challenges and social, emotional, and legal troubles, the students got along very well. I theorized it had to do with everyone being so individually quirky in their personal issues that they instinctively respected each other’s right to be whatever each presented. Many had been damaged by chaotic home lives, drug or alcohol use, or unpleasant school experiences. All needed nurturing until they could fly on their own. Overall, they could be loudly outspoken, brassy and brash, boisterous, and intimidating. And yet, they brought out the best in us, their teachers, in their demands and needs for attention, acceptance, and a relevant education.

Although the students expressed themselves with a wide variety of clothing styles from jellabas and hijabs to Goth to New Age to cross-dressing, and accessories from tattoos to every piercing imaginable, Von was a standout in his Buddhist robes. During his first few days, I kept a close eye on him; but to my relief, he fit right into our nest of “wounded birdies.” Classmates taught him to say, “Wassup, bro!” and all manner of variations to the traditional fist bump. He strode about the school in a bubble of serenity, exuding calm the way some flowers exude fragrance.

He subtly changed our student body—it became calmer and less raucous when he was present. One day, a new student could be heard guffawing and joking loudly before class. The ever-gentle Mr. Howard pleaded with her to lower her voice.

“WHY I GOT TO BE QUIET? CLASS HASN’T EVEN STARTED YET!

Suddenly, classmates turned, admonishing her, “Von’s come in. Quiet down!”

“WHO THE HELL IS VON? I DON’T CARE! WHA’ THE F—?!?

“He’s a monk,” intoned Kelly, tossing off a nod in Von’s direction.

Following his glance and seeing Von in his flowing, orange robe settling into his seat, she sheepishly muttered, “Oh, my bad. I didn’t know.”

Von soon gained a following. Students trailed after him, seizing opportunities to speak in quiet, earnest voices between classes, in the hallway, in classroom corners, and outside in the breezeway. It got to the point where he needed an office. And after giving it some thought, he found one.

“Ms. Lau, can I come at lunchtime to talk to students?”

“Sure, Von, but only if I can stay to do my work. The rest of the room is yours. When are you eating lunch?”

“Yes, you stay,” he said “No lunch. We eat one time a day.”

My desk was in a corner aligned with the door at the other end. Next to the door was a large, plate glass window facing the breezeway. Von sat in the diagonal corner from me while the other student faced him, deep in low-voiced conversation. After a couple of weeks of watching a steady stream of students stop by, peering in the window to check on his availability, I had to know—what were they whispering about?

Von replied, “Sometime girlfriend trouble. Family problem, fighting, like that.”

Astounded, I exclaimed, “But you’re a monk! How can you advise on girlfriends?”

“They tell me problem. Like fight with girlfriend. I say be nice. Say sorry, do good.” And then I got a mini-lecture on applying Buddhist principles of compassion and peace to human relationships.

In between peer counseling sessions or on slow days, Von studied Sanskrit, explaining that he wanted to read the scriptures in their original language. Then one day, he shared how he became a monk: his mother brought him to the local temple and gave him to the monks to learn a life of service. He was three.

I was appalled. A three-year-old, abandoned! Then he added his mother brought daily meals and necessities for him and extra food for the monks. As a young child, he could eat more often, but all monks were supported by the once-a-day meals prepared by the laity. In fact, by custom, all unmarried men and boys spend time in temple service for a few days up to a few weeks, but in Von’s case, his mother intended for him to be raised in the temple. He never asked her why preferring to trust her decision. An apprentice monk when he enrolled in Middle College, he later applied for and received excused absences from the Attendance Secretary, Ms. Gentry, to travel to California for his novitiate ordination on May 16, 1996. He was a junior.

Another time he related how the senior monks and he went to Chinatown for their evening meal. The waiter repeated their order but Von stopped him, pointing out, “We want Beef Chow Mein. You forget.”

An argument ensued, with the waiter insisting he would only fill vegetarian orders for them. Von patiently explained that in Theravada Buddhism, monks can and do eat meat, but the waiter still declined to add the dish, firmly stating, “Monks don’t eat meat. You are testing me. I’m not going to hell because I served meat to monks!”

They canceled the order, and with much grumbling, left to find another restaurant.

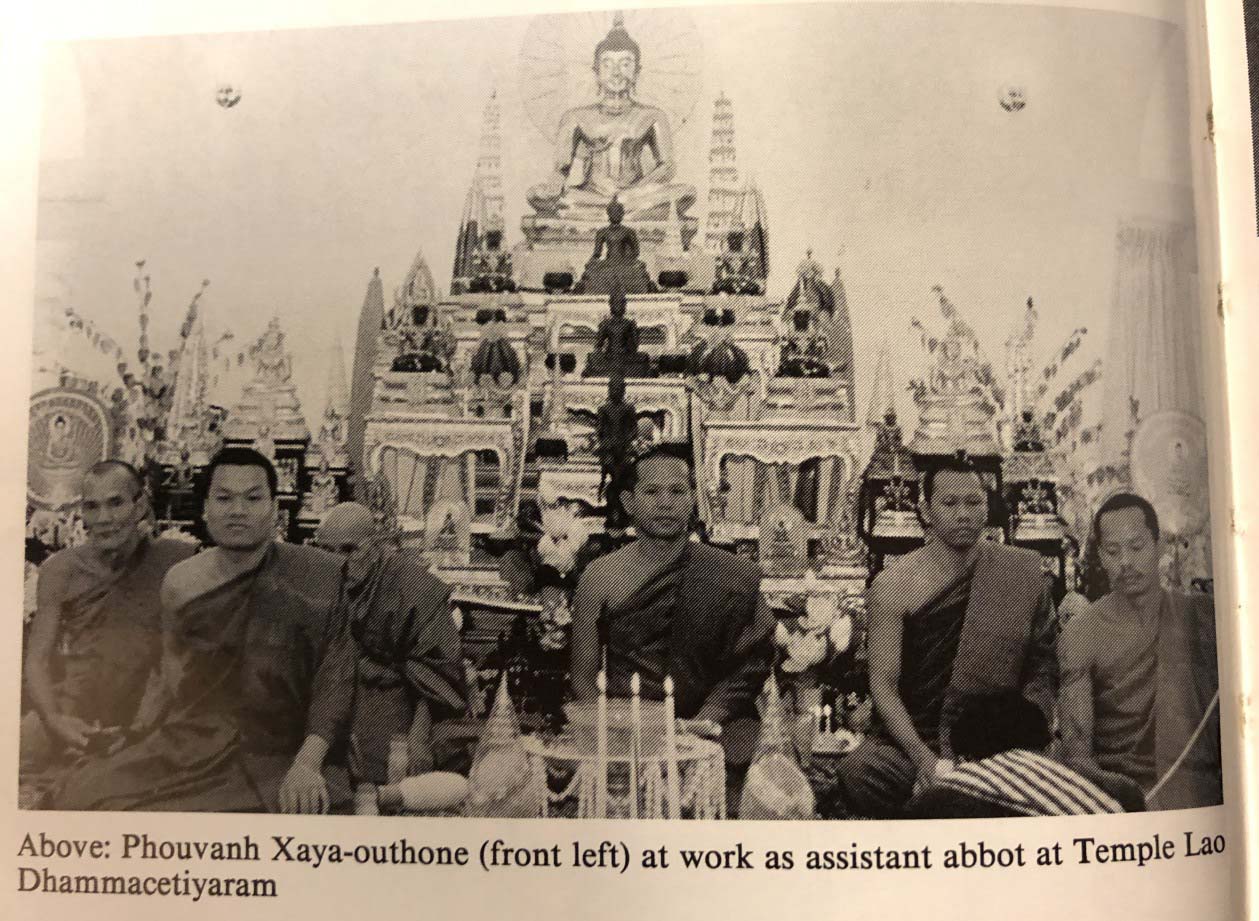

Due to his increased responsibilities, Von was promoted to Assistant Abbot, managing all temple affairs requiring English, pressing me into occasional service as an advisor. When school was almost out, he casually asked, “Ms. Lau, do you want to come to temple to see Lao Prince and take pictures?”

Surviving royal family members had escaped the Pathet Lao to live in exile in Paris. HRH Crown Prince Sourivong Savang came to Seattle with his uncle to plan the first Lao Diaspora Community Conference to be held for three days in the fall. The Crown Prince had come to look over possible facilities. Part of his itinerary was granting a royal audience to Abbot Khampuey and other monks. Of course, I accepted the invitation! As Assistant Abbot, Von would be an important part of the royal courtesy call, and I wanted pictures for the yearbook.

On the appointed day, I arrived a few minutes early at Temple Dhammacetiyaram on Martin Luther King, Jr. Way South. Outwardly, it looked like a house, but the interior had been modified to meet temple needs. I knocked.

The monk who answered didn’t speak English but he understood when I repeated Von’s name. He went to get him. Seeing the pile of shoes in the entry, I removed my own. Von came and led me to the main room. Two burly bodyguards stood at the doorway, frisking each person waiting to enter.

Nervous, I clenched my jaw and hissed to Von, “I don’t want those men to touch me.”

He nodded gravely, adjusting his robe, “No worry.”

When we came up to the doorway. He spoke to the men, and after a short exchange, they stepped aside, gesturing at me to enter. Everyone sat on pillows on the mat-covered floor, with the Crown Prince seated on a low lounger at the end of the room, leaning toward the Senior Abbot, who was flanked by Von to his left. I sat on the opposite end of the room but had some freedom to move around for photo ops. The royal audience lasted well over an hour, the purpose of which was for the Prince to hear reports on how the community and temple were doing economically, culturally, and religiously.

Afterward, I asked Von, “What did you say to the bodyguards?

“Oh, I say you my teacher. No touch.” I wasn’t entirely convinced that was the entire exchange because it was a lot longer than the interpretation, but he declined to tell me the rest of the conversation or what the royal bodyguards had said about me.

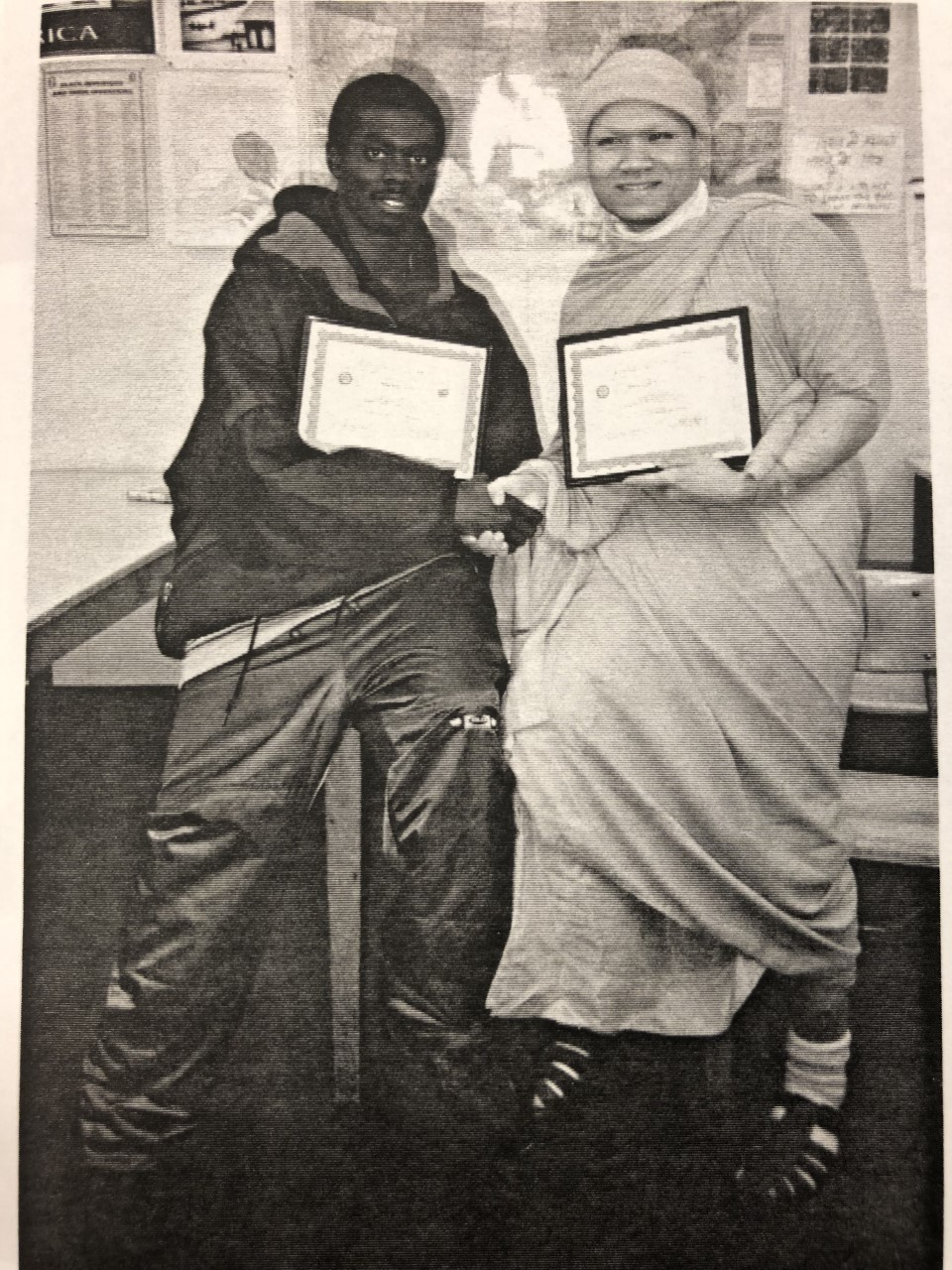

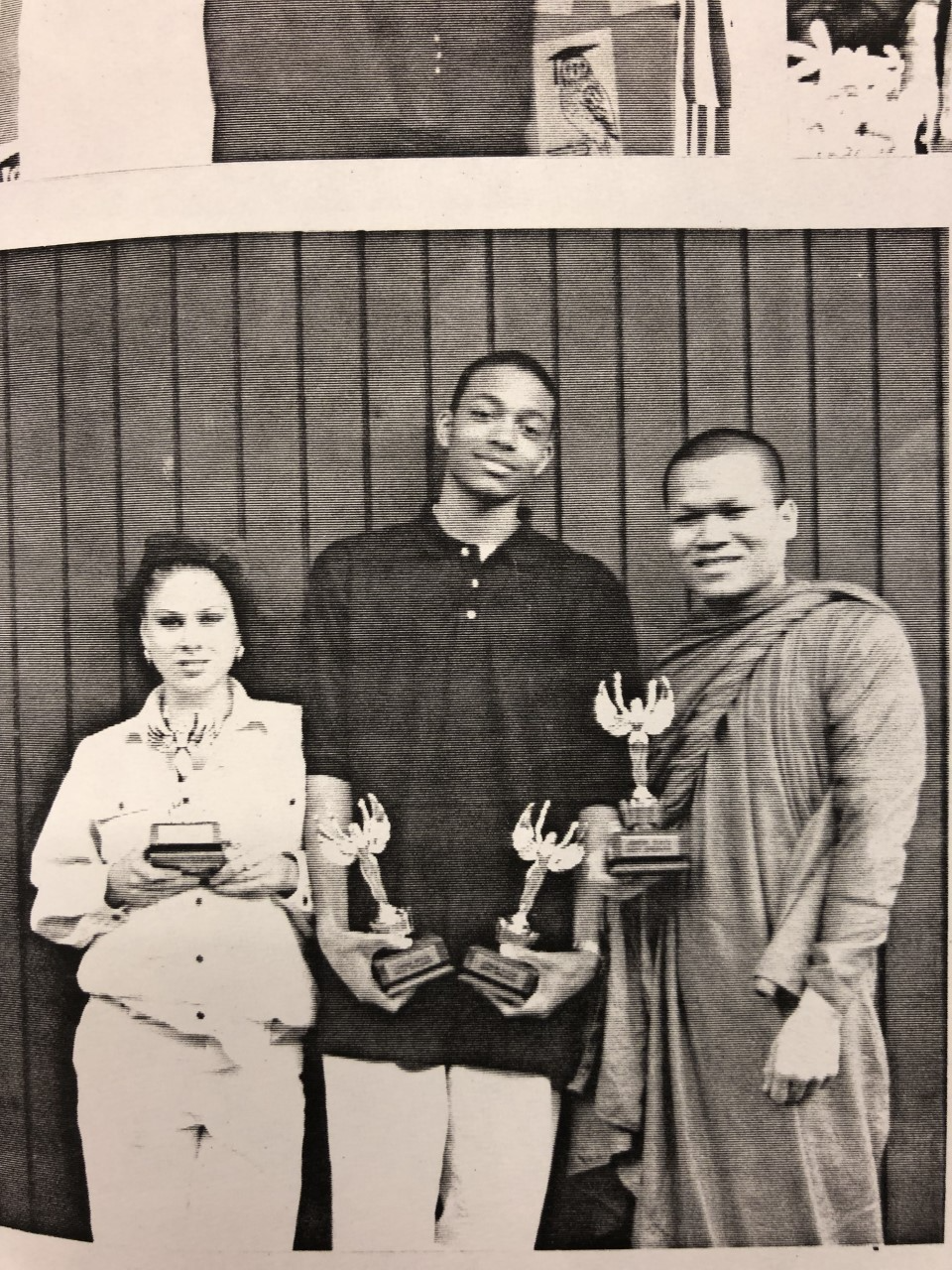

In May of his senior year; the faculty and student body selected Von as the school’s nominee for the prestigious Westin Peacemaker Luncheon Award. He was ecstatic at being named one of the area’s premier high school peacemakers. The Flora Cole Scholarship soon followed, then the Rotary Club Hidden Winners award, and finally, the ESL Department Award.

Despite his awards, Von became noticeably sadder during the semester, even his posture seemed stooped, as though he were carrying a huge weight on his back. I guessed it might be his workload at the temple. Planning was underway to enlarge the footprint and alter the exterior to be like the temples in Laos.

As Von’s English improved, he gained more and more responsibilities at the temple until he was de facto Abbot in charge of English matters, and I became his Chief Counselor, advising on topics ranging from fire inspection compliance to what to do about theft from the collection box to helping read and respond to correspondence in English. His stress rose to all-time highs when he figured out who was the collection box thief. He couldn’t bring himself to talk to this elder nor turn them into the police, which is what I suggested he do.

As the end of the school year approached, he eagerly shared some news: he had resigned as Assistant Abbot. The responsibilities were far too great, and the stress unmanageable. After resigning, he reverted to his former happy self.

All too soon graduation day arrived. Sumptuously decorated with tall vases, gigantic ribbons, and huge displays of floral creativity, the Seattle Convention Center scarcely contained the joy of hundreds of grads from SCCC’s many departments and programs. Our seniors marched with the high school completion grads in one continuous line. Two weeks later, the temple congregation hosted Von’s graduation party, to which the faculty and support staff were invited. Such an amazing feast of flavors and aromas!

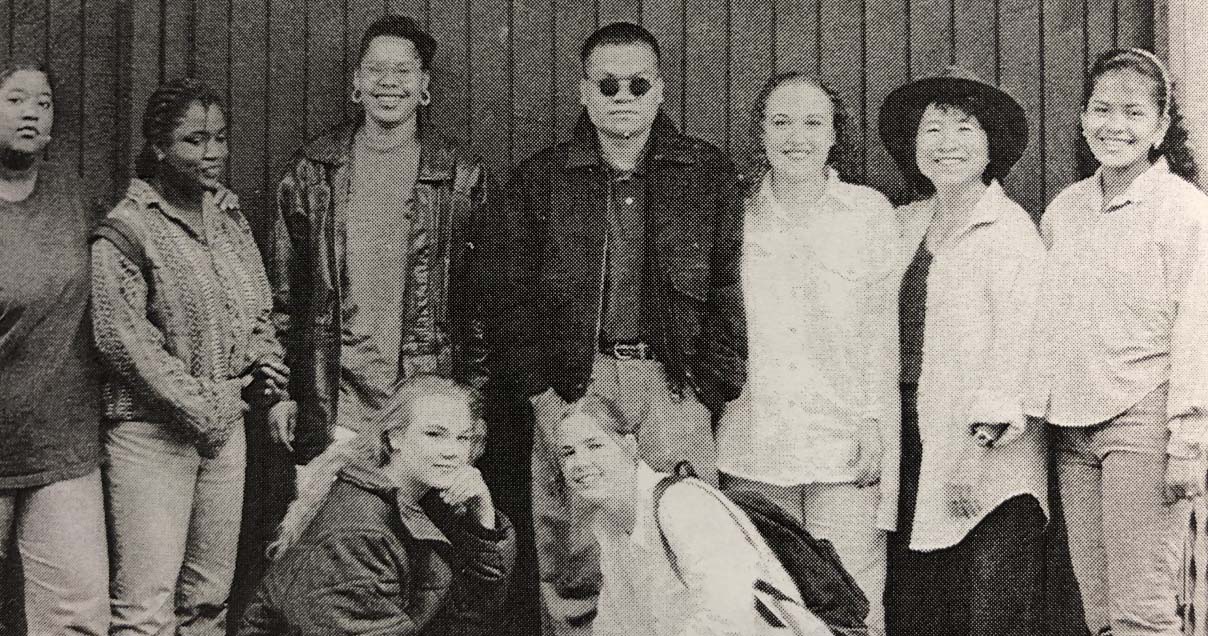

Because the MCHS underclass student classes weren’t out yet, Von returned for a surprise visit in street clothes: a polo shirt, slacks, and leather jacket, complemented by a pair of jaunty sunglasses. All that was missing was a motorcycle.

Smiling broadly, he announced, “Ms. Lau, I am a layperson. I can shake your hand now. Can we do that?” he inquired as he extended his hand.

Shaking hands didn’t seem adequate. “Can I give you a hug instead? You look wonderful!” And so our extended handshake became a hug.

He explained that his three years as a novice monk were over and that before taking final vows, each monk returned to the life of a congregant for one year prior to the taking of final vows. It ensured that the novitiate knew exactly what he would be leaving forever. Von planned to get a job, find a place to stay, and eat more than once a day. I wished him the best as he went off to say hello to his other teachers and former schoolmates.

The summer passed quickly. Another school year began and ended. Von visited again, but this time he was back in the familiar orange robe and sandals. The life of a layperson did not suit him. He missed the discipline of the order, the structure, the rituals, and the rhythms of temple life.

Although he didn’t know when, he said he had decided to leave Seattle to pursue a lifelong dream—to travel to India to complete his study of Sanskrit, his goal being to read the scriptures in the original. And of course, to visit the birthplace of Buddha.

Then he reached into the opposite sleeve of his robe and pulled out the photos I had taken of him with HRH Crown Prince Sourivang Savang, gently explaining that monks are not allowed to have private possessions. He asked me to keep them safe until the day he returned to claim them. We both knew he wouldn’t.

Middle College closed its doors in 2001. We had lost our space, a one-level warehouse-like structure remodeled by the Carpentry Department for classrooms and support staff offices. Sound Transit needed the site for a staging area, so our ESL refuge, Room 110, and the rest of the school building would be demolished, along with two others on the lot. I transferred to Garfield, then Franklin High School.

Von and I stayed in touch through the occasional phone call. One evening, I read in the newspapers that the Dalai Lama was on a world tour to give talks in various cities. One of his stops would be Seattle. Tickets to hear him speak were free, but almost impossible to obtain.

Von called, asking if I wanted to see and hear the Dalai Lama speak during his Seattle stop. I quickly accepted, but the condition was I had to drive Von and three other monks to the event at Qwest Field. For me, it was a tiny favor for the privilege of listening to the Dalai Lama speak about the nature of compassion.

Our seating was so high and far away that I mostly watched the giant screens instead of the stage where the Dalai Lama sat in an oversized, red armchair. He looked like a tiny doll in that oversized chair.

Warm and humorous, he delivered his remarks in impeccable English.

After the speech, I drove Von and the other monks back to the temple, listening to the cadences of their animated discussion in Laotian, imagining what they might be saying about the Dalai Lama’s long talk.

I have not seen Von since.

A friend, who had been our school’s instructional assistant for Laotian, Mien, and Hmong ESL students, asked about him at the temple, but she couldn’t find anyone who knew where he was or how to reach him.

Over the years, I have wondered if Von ever achieved his dream of journeying to India to visit the Buddha’s birthplace and reading the scriptures in Sanskrit in that sacred space of quiet contemplation.

I like to think he did.

Acknowledgements

Frank Irigon

Chanhom Lee

Seattle Times Archives

Wikipedia

Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience