Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

A Filipino Perspective of Black-Filipino Solidarity in Seattle

by Jasmine M. Pulido

When I was growing up, people like me were missing in American history books. The legacy of Filipino Americans’ contributions to larger social movements on local, national, and international levels was completely muted. More importantly, the cross-cultural solidarity that Filipinos and Filipino Americans built with other marginalized communities was and continues to be minimized, if not completely erased, from our educational system and mainstream knowledge.

This erasure is a concerted effort on multiple levels. This deletion is on purpose.

When it comes to the Black community specifically, I have found in my research that my ancestors and the ancestors of my Black community trace all the way back to pre-colonized Philippines. Tracing back to African migration patterns, the Aeta, Agta, or Ayta people were the first Indigenous Filipinos living about 20,000-30,000 years ago. In other words, there were no “my Filipino ancestors” and “their Black ancestors.” They were one and the same.

Tens of thousands of years later, when American troops attempted to colonize the Philippine Islands during the Philippine-American War on February 4, 1899, Black Buffalo Soldiers were sent to fight against the Philippine Army of Liberation. During that war, David Fagen, a Black American soldier, deserted the U.S. army to take up arms with Filipino revolutionaries. He went on to lead ambushes and assaults in guerilla warfare and became affectionately known as “General David Fagen”. He wasn’t alone either— as many as 15 other Black Buffalo Soldiers left the U.S. Army to support the liberation of their Filipino comrades.

About a decade later, the first recorded Filipino in Washington state came as a war bride, also married to a Buffalo Soldier. Rufina Clementine Jenkins and her husband, Frank Jenkins, first moved into Fort Lawton (now called Discovery Park) in 1909 with their Black and Filipino children and later settled into Ballard. This pattern became more common as many of the first Filipino families in Seattle were mixed-race Black and Filipino like the Jenkins family.

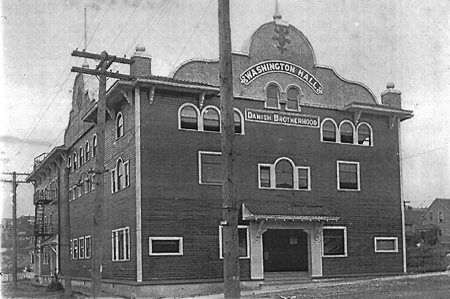

Interracial marriage and intermingling between Black and Filipino communities continued to take place as more Filipinos immigrated to Seattle and settled in Chinatown and the Central District in the 1920s and 1930s. During this era of immigration from the Philippines, called the “manong” generation, Filipinos moved into the Central District’s racial demographic which was predominantly Black. It is primarily in the Central District that these two historically marginalized communities lived in shared space together due to racially restrictive housing covenants that limited where they could rent/own property. Living in close proximity also provided the opportunity to build intimate and interpersonal relationships across racial lines at dance halls, pool halls, and places of work. While the Central District has been a target of mass gentrification recently, many of these Black-Filipino families are now 5-6 generations in the making as long-term Seattle residents today.

In the 1930s, Black and Filipino American community activists worked together to stop attempts to prohibit interracial marriage, and these two communities have been working toward political freedom on a unified front ever since. Of particular importance in the solidarity efforts of Black and Filipino communities local to Seattle are the formation and political change pushed forward by the Gang of Four during the Civil Rights Era in the 1960s and 1970s. Far broader than just Filipino and Black communities, the Gang of Four built coalitions across several communities of color as well as with progressive white activists in Seattle.

In the friendship of Gang of Four members Larry Gossett, Bob Santos, Bernie Whitebear, and Roberto Maestas, the personal became political as these four individuals rallied together to fight for liberation on multiple fronts from Native fishing rights to racial discrimination to housing laws.

“One of the reasons we stayed together nearly 40 years was because we met each other in the midst of the issues impacting the minority communities of Seattle,” said Larry Gossett, the last living member of the group at age 78. “As you can tell from 60 years of movement work, now the federal government has a difficult time dividing us when we come in as a united front– Blacks, Latinos, Asian, Native American, white, all working together.”

Thanks to their cross-cultural solidarity and the support they offered, institutions like Daybreak Star, El Centro de la Raza community center, The Filipino Community Center of Seattle, and the Office of Minority Affairs and Diversity at the University of Washington, along with many others, exist to serve the needs that span across the multiple communities still present in Seattle today.

Evidence of Filipino and Black solidarity can also be seen in other areas of Seattle’s history. For instance, the Seattle Black Panther Party had Filipino members including trumpet player Mike Gillespie. LELO (Legacy of Equality, Leadership, and Organizing), formerly known as the Northwest Labor and Employment Law Office, was formed 33 years ago when Black, Asian, and Latinx workers united to work toward economic and racial justice. The collaboration between DJ Nasty Nes (known as Seattle’s godfather of Hip Hop) and Sir Mix-A-Lot was a partnership that opened the doors for many rap and hip-hop artists in Seattle in the 1980s. Black and Filipino children still participate in the award-winning FYA (Filipino Youth Activities) Drill Team together, the nation’s only Filipino American drill team founded in 1959.

Amid this long history of solidarity, anti-blackness persists in the Filipino/Filipino American community. Filipino/Filipino Americans are called the “Blacks of the Asians”, negatively portraying both Filipinos and Blacks as the lowest position in parallel social hierarchies. This divisiveness originates from attempts by white supremacists to turn racial minorities against one another. The internalization of these racialized ideas into our communities is a result of white-centered agendas. With the preeminence of the Black Lives Matter movement alongside the increase in anti-Asian racism both locally and nationally, these tactics continue to be leveraged to perpetuate the same destructive power dynamics that pit Black and Asian communities against one another while casting the long-forged history of solidarity between these two marginalized groups aside.

Instead, we can choose to uplift the legacy this cross-cultural history of solidarity points to that is still seen in our co-existing and intermixing communities. We can witness this unity living today in the form of relationships, mixed-race families, local activists, community organizers, and emerging leaders in Seattle today. Less than a month ago, for example, the unity clap or “Isang Bagsak,” a practice that originally brought Filipino and Latinx farmworkers together to unite their efforts for farmworker rights across language barriers, was used by students and community members from Washington, Hawaii, and California at a SPS school board meeting in an effort to save the newly introduced Filipinx American History course, and other ethnic studies classes, from being eliminated.

Spanning from the widespread introduction of anti-trans legislation and the rollback of abortion rights to the death of more Black lives at the hands of law enforcement, the continuance of anti-Asian racism, and the loss of protection from COVID-19 for our disabled and immunocompromised communities, there is ample evidence revealing how the rights and lives of our most marginalized communities are still threatened. More local organizations have emerged to provide tools, resources, and space for the needs of our communities, like the Lavender Rights Project, Alphabet Alliance of Color (AAOC), and the Harriet Tubman Center for Health and Freedom.

Amid all of these sociopolitical issues, we can remember now more than ever the groundwork that our ancestors and predecessors laid for us across cultural lines. We can use it as our foundation, our inspiration to build an even broader, more inclusive movement.

“Oftentimes people think of our community leaders as these big, flashy people that are giving speeches but there are a lot of quiet people doing a lot of work of upholding the invisible people in Seattle,” said Lulu Carpenter, a Black and Filipino community organizer in Seattle and founder of AAOC. “They don’t want glory. They just want their communities to be safe. The truth is that people are building relationships that are beautiful, amazing, and strong… Those are the unsung network of love and greatness that is Seattle.”

Our work continues.