Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

The Power of Authentic Filipino-American Representation

Words and paintings by Cleo Pineda

As a naturalized citizen of the United States, people often ask me about my experience moving to a different country. Tumultuous. Being raised in a Filipino household where I ate dishes like Sinigang and spoke in Kapampangan and then needing to assimilate to my predominantly white peers who didn’t share the same experience made it difficult for me to relate to anyone. Throughout my adolescence, I struggled with feeling at home in the small city I grew up in.

Unlike my friends who could simply turn their televisions on and find parts of themselves in the characters they watched, I couldn’t see myself in any of the people displayed on the screen. With Hollywood’s lack of Filipino representation and often offensive portrayals of Asian Americans, I learned to hide the parts of myself that were not validated through mainstream media.

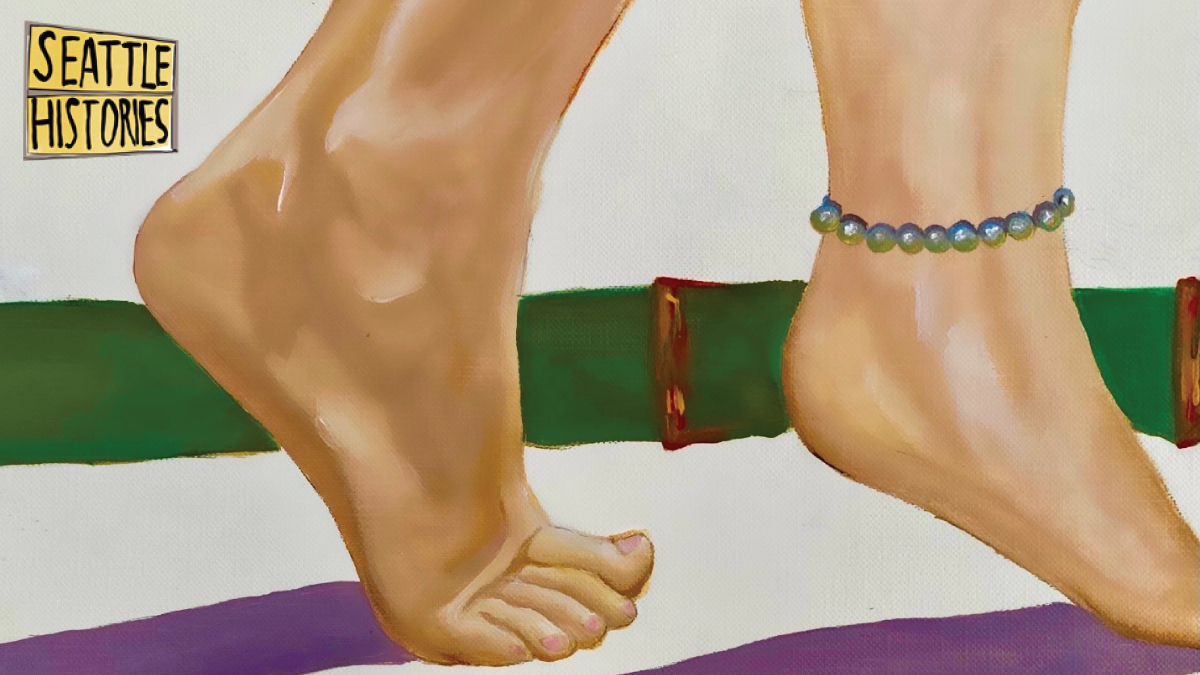

Cultural clubs such as Seattle’s Filipino Youth Activities Drill Team (FYA) are essential in helping young people identify positively with their ethnic heritage, especially in their formative years. Those who have witnessed FYA create tempos using bamboo poles, perform traditional folk dances like singkil and tinikling, or execute complex Eskrima martial arts routines, gain an exclusive look into a non-westernized version of Filipino heritage. Seattle’s FYA combats the entertainment industry’s historically false or otherwise watered-down depiction of our fellow Filipinos.

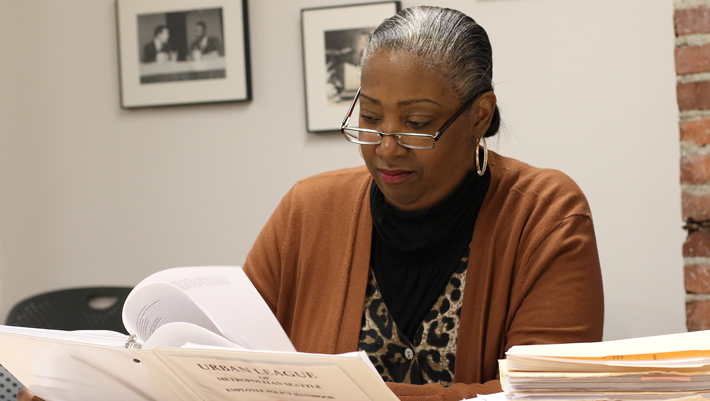

Founded by Filipino American activists Fred and Dorothy Cordova in 1959, FYA featured Mandayan Marchers, the Princessa Drill Team, and Cumbanchero Percussioners who all went on to deliver award-winning performances. By the early 1970s, FYA’s reputability among Filipino-American Seattleites garnered the team a strong volunteer base which propelled it to be the first Asian Pacific American agency to receive funding from the United Way of King County.

In a 2005 videotaped interview, the Cordovas chronicled the history of FYA, “FYA not only provided leisure activities for the kids…it provided the kids with a source of pride,” Dorothy explained. Despite their noble desire to promote the celebration of self-identity within Filipino youth, the team couldn’t escape the labyrinth of derogatory remarks and actions from some people in the community. “Once we [performed] out of Seattle, we faced two kinds of welcome. Either a warm welcome or, depending on the part of Washington state you were in, some terrible kinds of things like closing a state park once we got there, then having someone sit at the bench…to watch and see what we would do, then accusing us of dirtying up a park we just got into….The kids understood that there were two kinds of faces we would see once we went out. It was an awareness,” the historian revealed. In true defiance of the model minority myth, FYA willfully resisted all pushback against their efforts and continued to proudly perform outside of Seattle.

For the Cordovas, folk dancing means far more than just a few minutes under the spotlight. It is a form of storytelling to preserve the Filipino culture. Dorothy casts much light on FYA’s continued growth and success, “Most youth groups die when the people in the group leave, get married, go off…FYA was able to stay…because the people that were trained went back and trained the next group of people.”

The stories told through traditional dances have the power to represent the collective memory of Filipinos, and their life depends on them being passed down from generation to generation.

“Our stories are in our people.” – Fred Cordova

If I could travel back in time and talk to my past self, I would tell her that she isn’t alone. There are still kids in America today who could use a safe space to learn more about and practice their cultural traditions. Even if a lot of work still needs to be done for Seattle’s BIPOC communities, FYA’s advocacy for my culture reminds me of the accomplishments made by those before me whose work shows me that my Filipino-American identity and story matter.