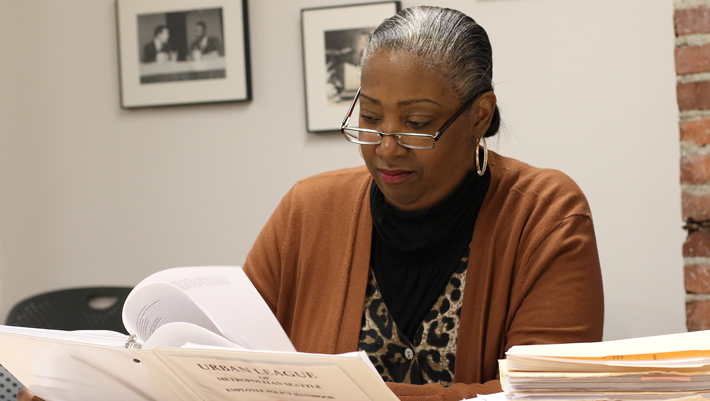

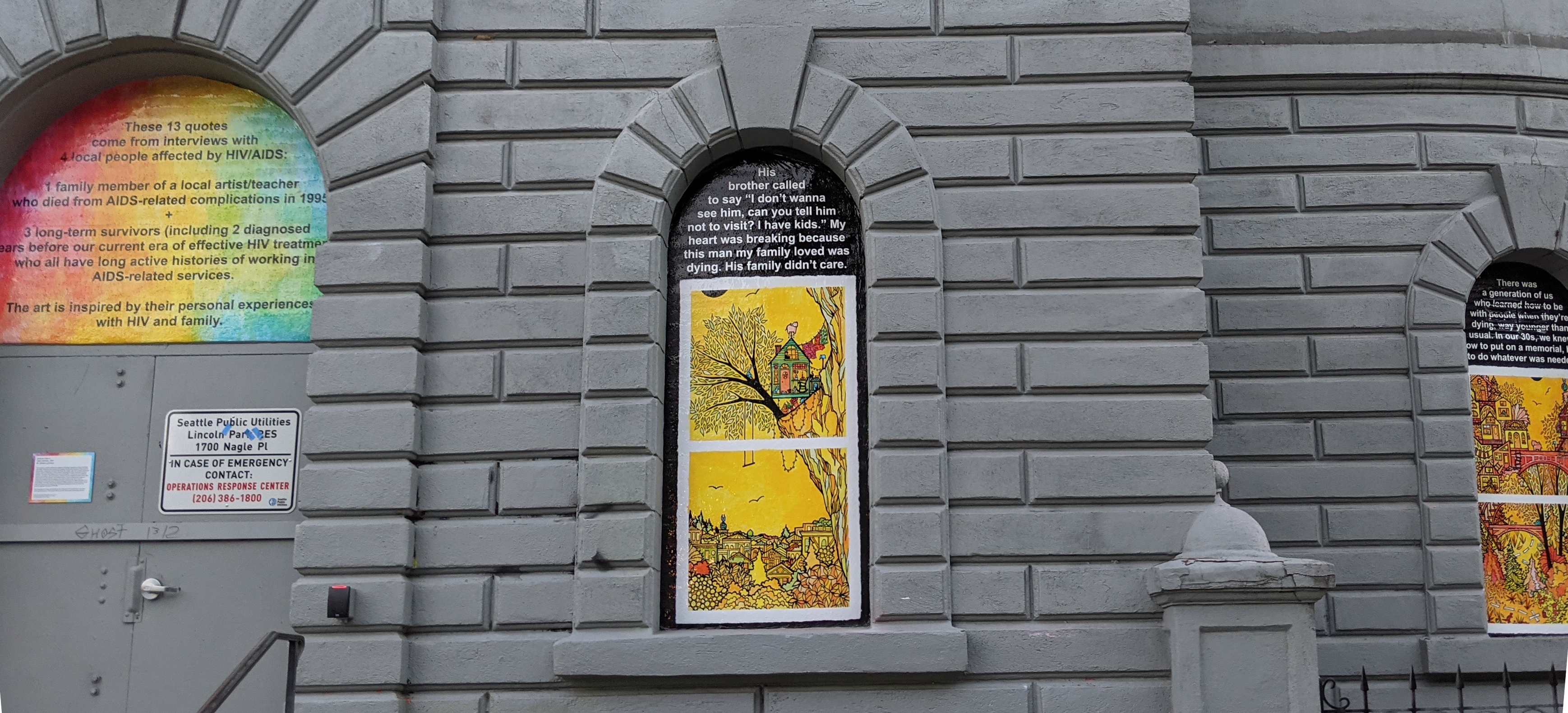

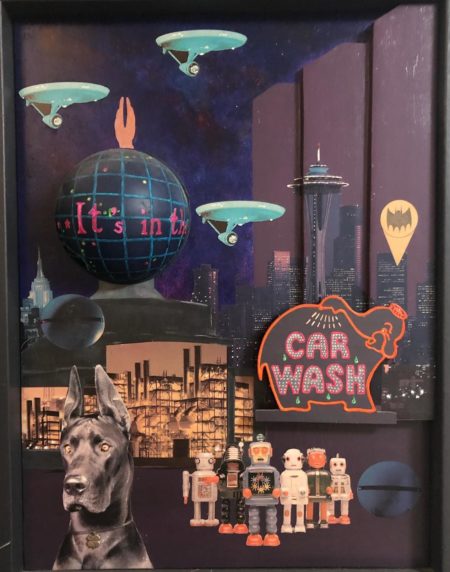

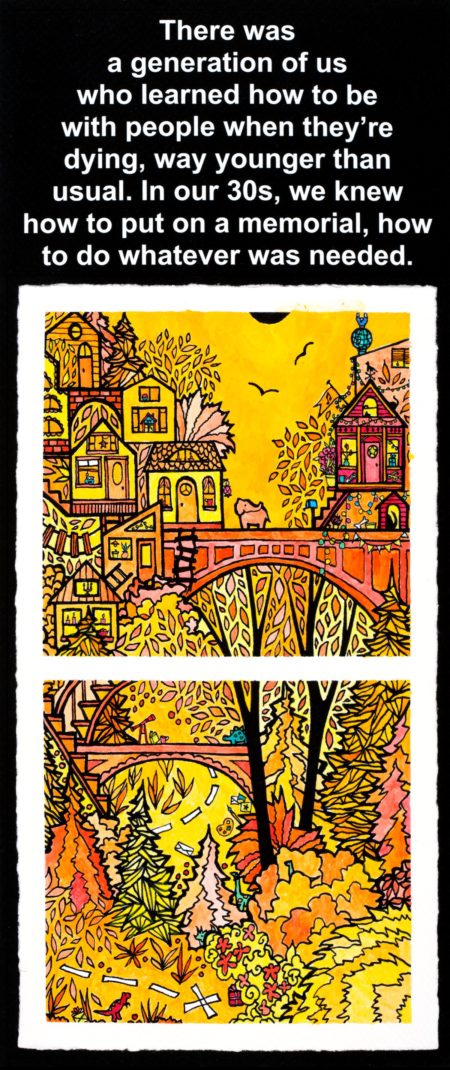

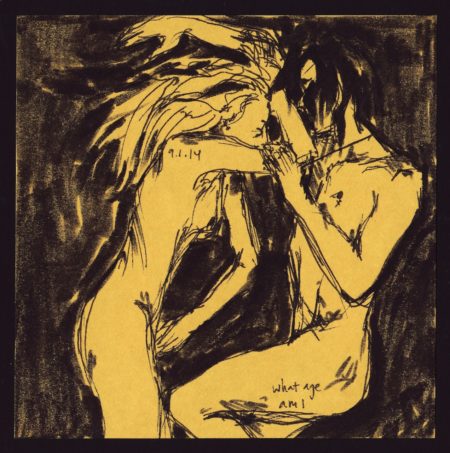

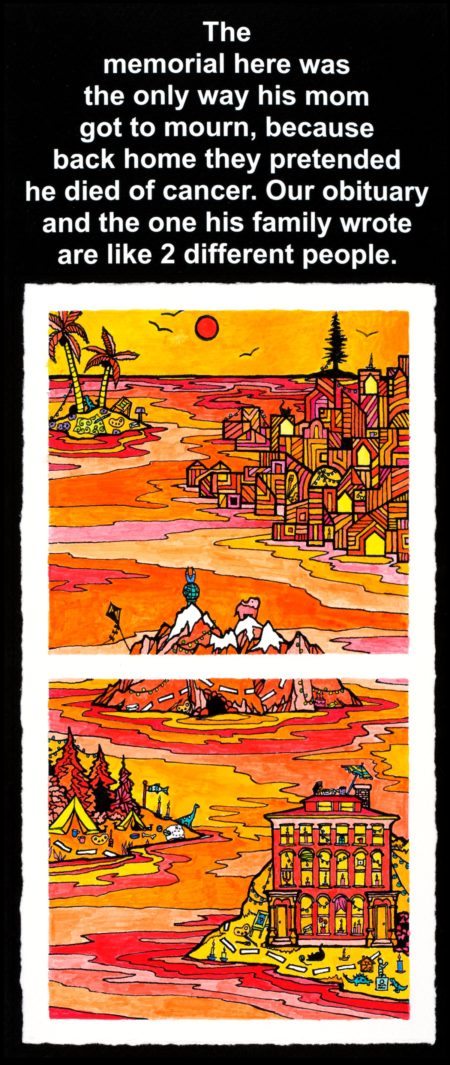

“what we make it” by Clare Johnson. Temporary Public Art Commissioned by the Office of Arts and Culture. Installed in 2021. Thirteen pieces of window art inspired by interviews with four local survivors about their experiences with HIV and family.

“what we make it” by Clare Johnson. Temporary Public Art Commissioned by the Office of Arts and Culture. Installed in 2021. Thirteen pieces of window art inspired by interviews with four local survivors about their experiences with HIV and family. Historic preservation in Seattle begins with community. The Seattle Histories storytelling project highlights the places, people, and events that have shaped the history of Seattle’s communities. These stories, told by community members, emphasize experiences and narratives that may have been overlooked or misrepresented in our city.

We All Have Different Memories

by Clare Johnson

1. There’s a lot I don’t know

I was born in Seattle just as the first signs of HIV were surfacing here. I could say I never knew a world without AIDS, but at the same time, I also don’t know exactly when or how I first learned about it. I don’t remember ever hearing of it as GRID. I don’t know if my parents were thinking about it as early as that or not. As a child, the fatal threat of it felt personal but I didn’t know why. I don’t know why I thought it was coming for me, for my people specifically, my family looked blandly safe enough, more or less. We were the first generation to never know a before time, and maybe every kid thought it was coming for them for a while. I don’t know what I mean by my people, just a creeping vulnerability. I don’t know if my straight younger sisters feel this way. Some kind of lonely childish fatalism in my chest, or warily looking over my shoulder, grown-up expressions in my little kid scowl. I’m not sure how early I learned about the connection with the gay community. I am sure I knew the word AIDS long before I knew what gay or queer meant, or had any evidence that those words applied to me.

2. Historically

My parents always said our neighborhood was historically where gay people lived, but little kid me doesn’t really see it. I’m mildly suspicious, wonder how my parents think they know this. We have gay family friends but most of them live out of town. Our block seems like lots of Catholic families maybe, there’s something different about us but maybe it’s just we stay away from any church, or haven’t been here as long. It’s not till later that I see it, the yearly Pride Parade shouting happily along Broadway and bringing every summer into the park, Red & Black Books Collective on the corner by City People’s and the hardware store, Rainbow Grocery across the street, Toys in Babeland down the hill. It’s possible I noticed some more as they were disappearing.

3. Volunteer Park

Early on I feel different than the neighborhood girls I sometimes play with, I notice it most when my baby sister is born, they express a delight in her baby-ness that I don’t feel, never occurred to me to feel. Other than playing by myself or drawing, the absolute best thing in the world is time with my best friend Evan. We make up elaborate games, climb the metal dome structure at the Volunteer Park playground or splash around in the wading pool, proudly swimming with our hands pressed to the rocky concrete bottom. The park is full of memories and surprises and bigger worlds and things to climb on, the camel statues and the cedar trees like secret tents where you watch out for used needles though and also what might be a giant bus tire perched above the reservoir, we’re also pretty sure it’s a real dinosaur bone in the playground. At some point when I’m old enough to read, a spray-painted message appears on the sidewalk near the densely giant rhododendrons. A tidy small square filled with A QUEER WAS BASHED HERE / QUEERS BASH BACK, stenciled at intervals all over the park. My mom explains hesitantly that queer is a mean word for gay people, and it’s complicated, something about reclaiming language. Privately I wonder if they were bashed every single place the message shows up. I wonder if they’re ok, if they’re alive. I wonder if queers have to be fighting all the time, if the word holds violence inside itself. I wonder why I feel like something I know nothing about is part of me, I’m just a kid. To be honest, even now in middle age I have this pinched-up feeling it didn’t say bashed, that it was saying murder, but I can’t find anything about it when I search.

4. Never thinking marriage

Adulthood started in another country, gay marriage ban years living away to stay with a partner met in college, out of three passports between us England was the only country with civil partnership laws that would let one of us immigrate to join the other. At the end of my twenties our partnership breaks spectacularly, the stress of a million things—hard trying to be an artist, hard living where you never wanted to be again, I know it was hard for her, money the weather endless bad jobs and we’re young it turns out too. Even so, I know the whole time how privileged we are to have that one passport. I grew up never thinking marriage was possible, so thoroughly that it’s never the first right I’d fight for, deep in my heart I don’t believe in it as a legal institution or personal goal. But still it ends up shaping the landscape of my life. I come back to Seattle on my own years before the laws let up. By the time I turn 30 I’m living in Capitol Hill again, same quiet-ish hilltop part where I grew up. I’m grown-up, queer bars like the Wildrose I’d only seen from the outside as a teenager are now open to me, but there’s this huge straight nightlife crashing down around us too, old friends moving back are all laughing bemusedly how the neighborhood has changed. Straight female friends get catcalled appallingly in ways I blessedly don’t, but there’s drunk homophobes and tourists to worry about too, at night I feel safer on the emptied side streets.

5. Musicals

Kid me loves trips to On 15th Video, an impossibly narrow space lined with VHS tapes and brightly lit mystery. I never know what my parents will think of next. We rent old movies instead of kid ones—Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier in Pride & Prejudice, every single Katharine Hepburn / Cary Grant pairing, musicals like Singing in the Rain and Funny Girl. I like the musicals best when it’s easy to imagine the leads as the best of best friends for as long as possible. The part I hate most is the moment when things get romantic between Maria and the Captain in The Sound of Music, it does not feel like a coincidence that shortly thereafter the movie world explodes into Naziism and bodily peril. My Fair Lady lets me believe the whole way through, even if he is clearly an abysmal best friend.

6. Neighborhood kids

Elementary school is just a short walk away, our watchful parents have diligently, complicatedly secured spots for Evan and me at TOPS. The gentle neighborhood girls walk with me some mornings, splitting off up the steps into Stevens while I cut across the concrete yard to the wooden portables behind. Some mornings when both my parents are at work I go a few doors down in the early dark to another kid’s house, play by myself with his big sister’s She-Ra dolls. Later it turns out that kid is gay too, in high school I run into him at all-ages concerts at the Meany gym, in our 30s he becomes a men’s rights activist online, unrecognizably hateful, dies young from something undiagnosed, his sweetly fierce mom finds him in the shower I think. She gives me middle school photos of him right before she dies too. I recognize the other kids in the photo, it’s their 8th grade graduation from Washington, that’s another of the queer kids from my high school dressed up in KISS-style makeup with a star over his eye, made teenage me laugh, died by suicide as a grown-up. Every time I walk by their old house I want to protect somebody.

7. Cal Anderson Park

During the years I lived away the little-sister-soccer-games playfield near Broadway strangely spawned a sparkling new park, the adjoining reservoir’s darkly-fenced weird expanse of sudden urban water is now lidded demurely with grass and public art and a pyramid fountain, swarming with sunbathers and dogs. It’s named after Cal Anderson, the first openly gay member of the Washington State legislature, who died from AIDS complications halfway through 1995. Trying to rebuild what little art career progress I’d made in England, nursing my divorced heart and feeling a foreigner in my own country of origin, I stroll through the park with the baby I’m nannying part-time. Caring for this baby is, funnily enough, perhaps the first thing that makes me concretely thankful for the life I’m trying to make back home, she is sharp and hilarious at 7 months when we meet. Some days it feels like every LGBTQ+ person in Seattle casually owns this park, an open green riot of queer laughter in all directions and I wish I’d dressed snappier and knew everyone somehow. Other days it’s other things, flattening or twisting as quickly as the Northwest weather. When I search ‘Cal Anderson’ online now for this writing, info about the park far out-muscles any entries about the person.

8. I feel I need to explain

Even though Evan is there, elementary school shocks me to my core. My difference is vulnerable, it seems to be something other kids can see on me. They make this sharply clear but in unpredictable moments, I never seem to be able to prepare. I still laugh with him and make other new friends but being best friends with a boy is apparently part of what’s wrong with me. Hiding or changing never feels like an option, I just have to do my best to watch out so it doesn’t surprise me too badly. Honestly, as a grown-up, I’m still not sure what they saw. I know I wasn’t the only one struggling. Little kid me watches out tiredly each day and watches everybody else’s inescapable hurt too, and yet I can’t quite get us to be in it together. The world is baffling. Years later my mom reflects in a letter to teenage me, “I distinctly remember telling you you it was cool to be different—to be left-handed, to not love baby dolls, to go your own way and not that of the girls who ruled the Kindergarten social strata.” I take that fiercely to heart as far back as I can remember, I decide early there’s something wrong with the world, not with me. But it doesn’t make the schooldays feel any safer.

9. This sunny moment

Summer vacations we drive to Idaho to see my mom’s family. We bring children’s books on tape borrowed from the Henry Library, I love the dramatic curve of its ramp, sweepingly elevated and wide against the squat 1970s building, look for Rae the librarian who gives us new book ideas, secretly relish the way everything looks weirdly yellow inside. But riding in the minivan I prefer music cassettes made from my parents’ old records. In this sunny moment we’re listening to something new, music by my dad’s college friend Judy Fjell. Most of her songs seem to be about nature or politics, a catchy refrain calling to ratify the ERA leads to some intriguing talk in the car, I think part of childhood me had hopefully surmised that discrimination against women was more of an old-timey thing. In school it always seemed to be presented as something historical, no longer debated—it wasn’t till high school that I noticed lower scores on my math tests for the exact same answers, or art school when I saw the cis men’s artistic intentions trusted more. But the most interesting thing about Judy’s music was the love song. I don’t know what exactly I said, but my dad casually corrects me—this song is talking about a woman.

10. Far-fetched

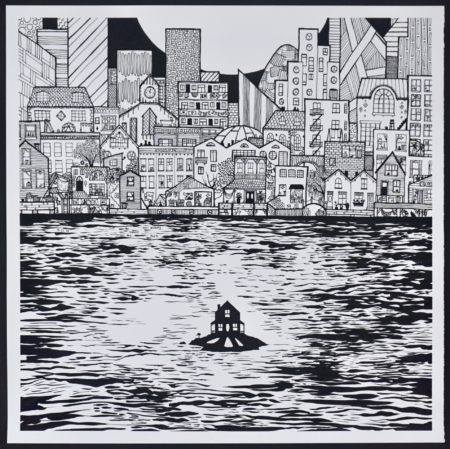

By the time I’m in my mid-30s I finally trust that I can keep my art career going back here on my own, maybe even grow it. I’m still on Capitol Hill, I realize the constellation of privileges that allow me to stay there even as the shops I knew are closing, even as the new places are mostly too expensive. I’m meeting other artists and writers and teaching instead of nannying, between heading to Pony or film fests at the Egyptian and NW Film Forum or readings in the friendly grime of Hugo House’s living-room-turned-cabaret I still walk through Cal Anderson Park all the time. I’m getting by with the art but just barely, small drawings in the windows of the Safeway on 15th through the briefly-lived Community Artist Program or sold to friends. Dreams of public art feel incredibly far-fetched, but I fantasize about circumnavigating the inscrutable gallery world entirely—being paid for art, but art that everyone can see without having to pay for it themselves. Periodically I start to see school kid murals in the windows of the old reservoir building, the only structure left that tells you anything about what this park covered up. Time after time I turn to a friend, half-jokingly bemoan, “Why won’t the City of Seattle call me up and ask to put my art in those windows?”

11. Wait and see

Kid me on the road to Idaho wants answers. How did my parents know this song on the tape deck was about a woman? I’m sure it didn’t say one way or another. Dad explains, “When Judy sings a love song she’s singing it to a woman. Not a man. Because when Judy is in love, she’s in love with a woman.” I’d met Judy and her partners before, she’s funny and warm with knowing crinkly eyes, when she visits she and my dad always joke comfortably together and laugh so hard. But somehow listening to her tape is the first time I hear this crucial piece of information: not all girls are doomed to grow into women who fall in love with and have to spend their lives living with a man. I realize with growing envy that some woman are lucky enough to sidestep the usual fate, they grow up into lesbians who get to live with a woman instead. This sounds so much better to me. But I’m also gathering that lesbians are an unfortunately small percentage of the population. I’m getting good grades in elementary school, I know some math. The odds are probably bad for me, I think. Probably I will grow up and find out I’m straight. I guess I will deal with the disappointment if it comes to that. There’s nothing I can do about it, I tell myself I just have to wait and see what happens when I’m old enough to fall in love.

12. An artist

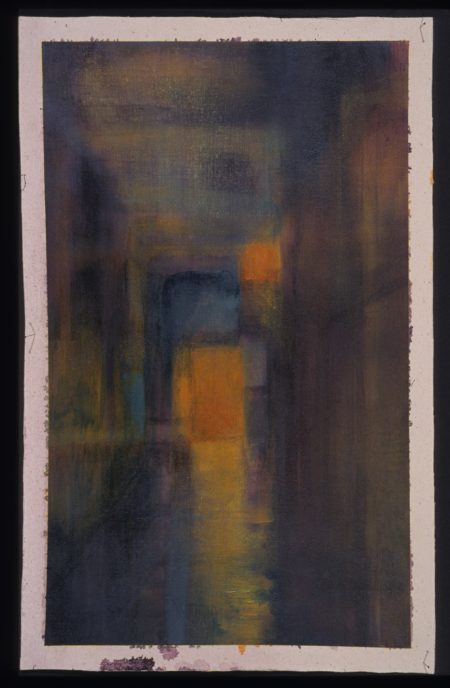

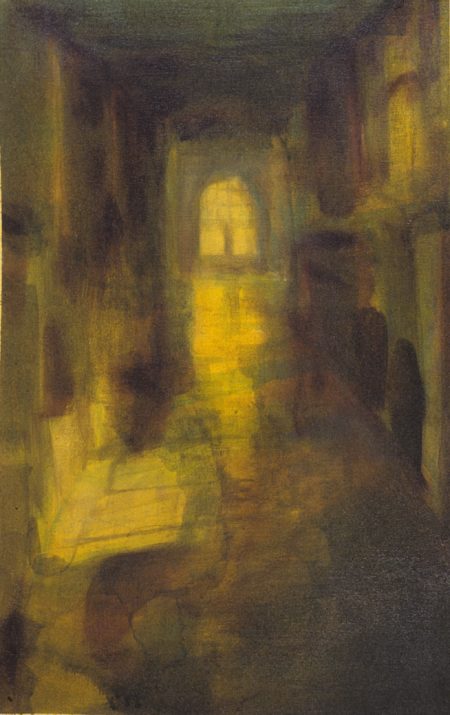

Despite the daily traps and vigilance, I do make school friends, it turns out later four or five of them stay friends for life even. On weekend playdates we elaborately play pretend, except my favorite games aren’t exactly pretend, it’s the set-up beforehand. Choose a category of toy, blocks or stuffed animals or dress-ups or stuff around the room, whatever. Take turns choosing till you’ve divided up all the pieces. Make a world out of the half you got, cleverly repurpose that chair as a bridge or a building or mountain, whatever you have has to be everything in the world, turn it around or pile it with this other until your limited choices fantastically turn into new ideas. Decades later in college I learn to say I like working with creative constraints. Another decade later when I finally have writer friends a fiction writer offers another phrase, world-building. The friend I play this way with the most is the child of an artist. Their house is always changing, her mom practices for installations on the walls with extravagantly mottled layers of shifty-colored paint. The morning light after sleepovers turns black bluer or even pinkish, different weather revealing secret moments of coppery yellows.

13. Old Fire Station

At some point in my childhood On 15th Video moves across the street into the old Fire Station No. 7, its intricately-bricked arches rising from the corner like a fancy castle keeping watch over the QFC parking lot. For all of middle school and a fair amount of high school I continue to think of this being the video store’s new location, even though now in the future no one seems to remember the old one at all.

14. I see this happening

In 4th or 5th grade our class takes a tour of the brand new Bailey-Boushay House. I’ve known people are dying of AIDS for a long time now, I don’t know how it’s explained to us but I understand that this is for them to have a place. The field trip is probably part of our yearly City School week at TOPS, we are seeing an installation by my friend’s artist mom Mary Ann Peters. My childhood memory is totally separate from the bland Virginia Mason medical website I find now, I picture clean newly-built halls conversely packed with personality, secret fleeting gifts around every corner. Mary Ann has made some sort of meditation room or vaguely sacred space, the memory feels small and cozy but sort of cosmically expansive, textured deep blues, flashes of delicate twigs, or stars. It’s the same colors as my dad singing Carly Simon at bedtime. Kid me holds this memory deep in my core, a space where art meets death and does something impossible. It’s a space so special given only to those who are about to exit unfairly, people who know they are about to be snatched away. My friend’s mother has given them this gift because she knows it’s not right, she knows they deserve something so much better than what’s happening. Her painted over and over again walls are offering a moment away from the terror unfolding on their bodies, she’s telling them silently I see you I see this happening.

15. Stay calm

I’m a 5th grader now. By now so many school days have piled up in my body, I know easily to tense when I walk through the classroom door into a world run by other kids. It’s unfortunate my desk is in the middle towards the front, I feel exposed at every angle. Drawing still keeps me calm but I have to do it on my own time. I guess it’s becoming clear to someone that I have to leave this school. My teacher Tom calls me into the hallway for some kind of heart-to-heart but I don’t understand the support, just feel nervous and exposed, unsure what he needs me to say. I don’t hear his words, I’m trying to think how to make him feel better and rush through the kind of awkwardness of it all. A handful of us leave class at times for some kind of group counseling in the small room at the top of the wood stairs, by itself above all the classroom floors. I think my tomboy friend who turned out lesbian too might have been in the group but memory is strange and I have no idea how we were identified for these sessions.

16. Friendly

One dark weeknight in early 2019 I awkwardly trudge through the February snowstorm flung all over the city, slipping in small steps down the hill and across Cal Anderson, emerging finally into the warm orange hush of a Seattle Central lecture hall. I uneasily remember my SATs there, was it the first, abandoned time when I rushed out faint with mysterious pain, ended my day in the ER slowly learning the bodily cost of all that vigilance? Or the second, replacement time, calm and uneventful. I’m here now for a Public Art Bootcamp hosted by Kristen Ramirez and other project managers from the Office of Arts & Culture. I’m so excited—after years of rejected applications to attend similar trainings run by the city, affirmative action has finally opened a door. I’ve been accepted to this session, specially funded by the AIDS Memorial Pathway thanks to their master plan artist Horatio Law, for artists personally affected by HIV/AIDS. I’m also nervous—so many of the artists seem to know each other, the guest speakers, the city employees. I don’t know anyone. Award-winning artist Clyde Petersen is sitting above me, I decide to take the leap and remind him we went to high school together, sort of, thank goodness he’s so friendly.

17. Art class

Remembering 5th grade I feel nakedly out in the open in some vulnerable, precarious way. But there’s this other completely opposite kind of openness too—I think of art class. I am almost all the way done with elementary school and suddenly, FINALLY, we are getting my first art teacher in school ever. His name is Rob, he comes down from the middle school once a week to lead us through dedicated art lessons with crayons and construction paper. From my earliest memories I always knew wanted to be an artist, but I’d never really known artists other than my friend’s mom. Rob talks so seriously about art, I dive in certain that these lessons were designed entirely for me, for my life to feel better. I feel so confusingly safe, so of a kind with this calmly funny stranger.

18. Serious art kid me

This brief burst of art happiness gets seared in my memory, boisterously holding hands with all the harder things that year. Rob directs us to listen to this music, draw the feeling of each different song while it’s happening. It never occurs to serious art kid me how funny and gutsy it is that every song is by Madonna. We move from ‘Holiday’ into ‘La Isla Bonita’ and eventually ‘Into The Groove’ and ‘Express Yourself.’ A couple years later when I’m old enough to get a boombox cd player for my bedroom, one of the first albums I look for is what I’d figured out Rob was playing, The Immaculate Collection.

19. Art history

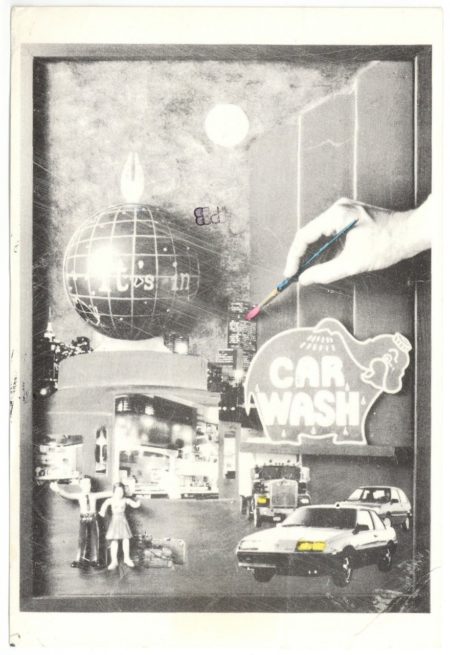

At this point TOPS had already relocated to the Seward building, expanding into older grades. One day Rob takes us uphill to the brick building facing the freeway for a special art history session. The middle school art room feels mysteriously darkened like some burgundy European academy wall, famous paintings emerging along the whiteboard ledge as if spotlighted. ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ is looking over her shoulder from velvety depths, eyes stunningly locked with mine. I know it’s a girl from the title, but she looks so charmingly genderless, or flexible, something so vulnerable and tough about her hairless bare stare, lushly shapeless cloth crowding awkwardly around her shoulders. ‘Cafe Terrace at Night’ feels like the most real version of nighttime anyone’s ever made, the endless community of colors in every color, brushstrokes always moving even a century later. It’s not till I’m in my mid-30s that I understand the world doesn’t look this way to everyone, a doctor I’ll never see again explains I have lifelong visual snow. Rob tells us about the artists and also explains the concept of forgeries, posing a question to the class—are these the real paintings, or copies?

20. Public art

In March 2020 I’m five weeks into a fantastically surreal artist residency at Crosstown Arts in Memphis, Tennessee. Selected after two prior failed attempts, it is perhaps the most glamorous my career has ever felt. I’m on the phone with a poet friend from home but the call drops— when my phone flashes ‘City of Seattle’ a second later I’m expecting to keep laughing sharply with her over whatever local writing world nonsense—but it’s not my friend on the line now. It’s a project manager with the Office of Arts & Culture, she’s overseen countless public art panels as they rejected my applications. “Are you familiar with the old reservoir gatehouse in Cal Anderson Park?” The City of Seattle is calling to ask me to put my art in its windows.

21. A private certainty

Vermeer and van Gogh fold together as favorites in my childhood brain, but those two paintings stay pulsingly crisp. After art history Rob brings magazines into our classroom, we choose photos to draw in the style of famous artists. My van Gogh-style horses emerging from water, sourced from a Marlboro ad and rendered in crayon, feels like the best art I’ve ever made. Those horses stay pinned to the ceiling above my bed till adulthood, a private certainty I gaze on when I can’t sleep. My cynical classmates know the answer to Rob’s solemnly sly question, but for me, those copies he made are more real than real.

22. The Gay and Lesbian Section

In middle school and high school, the video store changes from a place my parents creatively curate for me and my sisters, into a space of new agency. During daylight, I’m allowed to walk there on my own, choose DVDs myself. There are whole ‘Gay’ and ‘Lesbian’ sections, later ‘LGBTQ.’ I watch and rewatch so much 1990s queerness, tortured or campy or not-really-queer-but-sort-of or queerer-than-queer or totally over my head, adolescent me never knowing that decades in the future middle-aged me will be in some new friend’s apartment, a lesbian couple down the other side of Capitol Hill, laughing uproariously over the problematic sludge we got attached to as teens, movies I forgot about so long ago. Neither of them saw the one with suddenly naked k.d. lang in the Alaskan small town library. I don’t recommend Salmonberries but I don’t regret the strangeness of the memories. One of these friends grew up somewhere more conservative and asks, “Who’s k.d. lang?”

23. News about Rob

My memory is that sometime in 7th Grade I found out that Rob died of AIDS. I’m now confusingly in my second of two excruciating years at Washington Middle School, every morning my bus circles bleakly behind Acme’s chicken slaughterhouse on King Street. Future-vegetarian me leans my forehead against the window tensely as a solitary man in rubber rainpants hoses the concrete yard or we stop at a light alongside an arriving truck, its body a wall of cages stuffed with live chickens, feathers crammed against the metal. In 8th grade, I will surprisingly transfer back to TOPS where all middle-schoolers take a period of art, but at Washington art class is as it will also be in high school at Garfield—near impossible to get into. And yet for this one semester I’ve somehow strong-armed my way out of the home ec class I’d been assigned and into art, where I’d always wanted to be. I’m completely baffled that I’ve managed to make this happen. When I hear the news about Rob, I start an ambitious enlargement of my 5th-grade drawing using fancier oil pastels, two rearing horses emerging from van Gogh swirls of water. I think of it as being for Rob but he’s already gone, it’s just for me to put my feelings somewhere.

24. Surprise

After everything, my sexuality is still a surprise. I’m in a middle school friend’s basement, we’re joking again about hopeless crushes when this friend—who has already told me she herself is bisexual—gently detects, exposes the romantic underbelly of another one of my friendships. For months she’s the only person I talk with about this, because I don’t quite believe it. I’m just the same me, lesbians are so rare, what are the odds? And I’ve already spun so many of the usual crushes too, on boys I don’t know. It’s true though, I do feel some lurking romance softly couched in close moments with this one friend she’s asking about. During the present pandemic we finally reconnect after 15 silent years, sitting in her parents’ backyard with our backs to that same basement. I ask if she still identifies as bi, after a lifetime of only male partners, and even though this is barely a year-and-a-half ago I still don’t remember her answer.

25. There are things I can’t talk about

It’s going to be ok when I come out to my parents, don’t worry. Growing up I never had to ask who’s k.d. lang, they listened to her all the time. Her 1993 Vanity Fair cover photo, dapper and suited as Cindy Crawford suggestively shaves her smooth androgynous chin, was proudly flung all over our kitchen for months. There are things I can’t talk about but know that I know I am lucky, deeply privileged in my family of origin.

26. Research

The city wants my temporary public art commission to link with the nearby permanent works that create the AIDS Memorial Pathway, stretching from the Capitol Hill light rail station into the park. Someone suggested me from the list of participants in the AMP’s Public Art Bootcamp. As the first lockdowns hit my fancy Memphis residency, news alerts from the pandemonium back home in the epicenter swiftly crowding up my phone, I’m privately drowning in old AIDS archives research from King County. I’ve stupidly not budgeted enough time for spontaneous weeping, and my worry about both diseases is too close to home, too reasonable to ignore. Mostly alone in this giant abandoned-warehouse-turned-sparkling-arts-center, I once again think about Rob. I’ve always wished I knew more about him, every few years optimistically attempting another doomed internet search. Unsurprisingly, ‘Rob artist Seattle TOPS teacher 1990s AIDS’ yields no helpful results, no matter which combo I try. I don’t even know his last name. Who was he really. How did I even know he died? How did I know he had AIDS, I wasn’t even at TOPS in 7th grade. I try asking an old friend but she barely remembers him, definitely never knew he was sick.

27. Neighborhood gifts

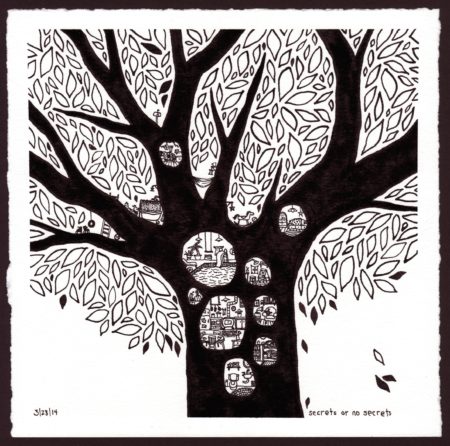

I get nostalgic for all the places that have disappeared, but being a teenager on Capitol Hill in the 1990s wasn’t that different from being a grown-up full-time artist here now—there’s a lot that’s off-limits, whether underage back then or money now or safety or whatever, but there’s also lots I love. My experience of the neighborhood has always been like a ruleless scavenger hunt, wandering into little surprises that sustain me, hold me, renew a sense of belonging. Even before I’m sure about my own orientation, Broadway has gently asserted itself as a space of easy adolescent freedom, walkable and full of pockets of casual queerness like Bailey-Coy Books. I look for any excuse to browse their shelves after school, just to feel of a kind with the grown-up employees. Sleater-Kinney and Mavis Piggott and SuperDeluxe CDs bought at Orpheum and Wherehouse Records and Cellophane Square are still beloved treasures years after those stores close, or the bands themselves call it quits. Each year when summer starts friends come over to walk down to the Pride Parade through Volunteer Park. Watching queer festival films at the Egyptian or the Broadway Performance Hall or Harvard Exit, rushing to a cheap matinee of Boys Don’t Cry in the cinema at the top of Broadway Market and hating the world, renting Wigstock closer to home and feeling gleefully certain that queer people are secretly magically-powered. Decades later a copy of Aimee & Jaguar purchased with a Beyond the Closet Bookstore gift card from lesbian family friends still sits on my shelf—still haven’t read it, too scared for the inevitable end. When things feel too expensive for grown-up artist me, there’s always that tiny green-gabled farmhouse hidden in the alley behind the 7-Eleven, rainbow flags and people lined up for free community lunch at the huge old brick church, giant boulder that turns out to be someone’s grumpy pet tortoise, the mysterious hand-painted mermaid signs that used to be in front of those houses on Thomas. Walks around the neighborhood are full of little secret gifts. Someday, younger me hopes, my art could be one of them. When I’m in my 20s in England, public art so impossible, this still becomes a foundational aspect of my work—I start making little homesick drawings, detailed worlds where ordinary human touches like mailboxes, laundry and mugs get to turn into special discoveries.

28. Help

Almost 30 years after our field trip I’m feeling suspicious of my memory, I can’t find Bailey-Boushay House anywhere on Mary Ann’s website. The Bailey-Boushay website is similarly close-lipped, sharing no details about magical art spaces. I email her out of the blue to ask. I’m afraid to find out my memory made it up somehow. But no, after a little back-and-forth—we’re all so busy working—she generously sends confirmation, photos and stories starting “Here ya go honey. Hope it helps.”

29. How did I decide that

I come out in some form halfway through 9th grade, but probably just to my parents and a few friends, probably just because things are going so lovingly bad with the close friend I’m pining for, or the menacing older boys on the bus who follow me to my locker sometimes, girl in my swim class changing room yelling what she’d do to any dykes if she saw them, I’m literally naked, attempting some kind of bodily disappearance into my clothes. At the same time it’s the mid-90s and sometimes Garfield High School feels full of spiky short-haired girls and long-haired delicate boys. A bunch of older students are actually visibly out, the genderqueer boy on the cheerleading squad seems to even be popular, I don’t really understand how all this works. Later on I find out these people were obviously still bullied, dropping out or leaving early for Running Start. During our Sophomore year we complain there’s been a mass exodus of the more noticeably LGBTQ+ kids in my age group, heading across the street to NOVA. I come close to leaving myself, but decide that this kind of high school world is something I have to learn how to survive, not escape.

30. The Boushay Solarium

I still haven’t been inside Bailey-Boushay since that elementary school field trip, but my memories of that room are real, possibly also overlapping with other installations—niches artists made throughout the facility—in her email my childhood friend’s mom calls them little worlds outside each room. She recruited Beliz Brother to make the Boushay Solarium together, in honor of Frank Boushay, her close friend Thatcher Bailey’s partner. I remember meeting Thatcher various times as a kid and hearing his name a lot, but no memories of Frank. Some part of lifelong me knew how Bailey-Boushay House was named, but another part of me now unexpectedly loses my breath at how concrete it is, how this place name joins two gay partners so publicly, has joined them for so long, before marriage was allowed, a joining flagrantly outliving all the laws and death.

31. Were we the first?

By Junior year I’m co-chairing Garfield’s brand new Gay-Straight Alliance. Our advisor Tracy tells us we’re the first in the Seattle area. Now I look back at old journals trying to find out how this happened, when I came out what I said to my parents, what I said to myself even at the end of those unfolding days. I’m testing my memories but get lost in these journals, flail ask friends for help, try to laugh at myself and start again. I’m just trying to find out when the GSA started or when I became aware of it but am wading through late-night-candle-scented pages of translucent teenage longing, a flood of hands held and cuddled homework and why won’t she love me’s, maybe she loves me. Did I even know I was gay when this was happening? I guess I did not.

32. Band names

In those earlier years my journal is flecked with song, band names slicing through sentences’ bared midriffs in casual shorthand as I list what’s on the radio. Sometimes love or hate or curiosity for the song changes my direction and other times my severed sentence just picks up after unbothered, unnoticing it’s been broken in half. I’m on my belly homeworking at the foot of my bed, ear to the boombox radio by my window. My friends all listen to DJ Marco Collins on 107.7, the favorite who unknowingly soundtracks our weeknights. The next day we joke about dumb song choices or earnestly compare new loves, bands to watch out for at Bumbershoot or RKCNDY or DV8, anywhere we get let loose on the loud grown-up world.

33. My reason for being

I still remember so much about running the Gay-Straight Alliance, it rapidly becomes my reason for being at Garfield. I become close friends with my shy younger co-chair, we form Safe Staff lists, lead staff trainings even, muster surprisingly huge participation in Day of Silence actions, anti-hate-crime awareness yellow ribbon campaigns, speaker panels in health classes, leftover Pride stickers all over my calculator and notebooks. Senior year I’m even a speaker in my own health class, a fellow student asks me how I feel about going to hell. Looking back now I know aspects were problematic, we’re so young and know so little but also that directness was thrilling, being so able to do something. Our advisor Tracy Flynn is not one of the teachers, she has mysterious extra capacities and brings in LGBTQ history presentations for our Friday lunch meetings in the health room, enlists the two of us to liaise with the school district’s Safe Schools Coalition, takes the group out to Broadway Grill every Dine Out For Life.

34. Dead ends

A few more weeks into present-pandemic Memphis, my calls to 5th grade friends all dead ends, I press my mom again. How did I know about Rob and AIDS? She’s the only person who remembers him with me, knows how much those art times meant. She doesn’t know how, but she’s clear we knew for certain. I tell her raggedly the info had to have come from her, no one else remembers him after our class, not even the kids who stayed at TOPS when I left. A few days later she sends me a text, she thinks he was housemates with my preschool teacher.

35. Seniors

Digging through my yearbooks there’s no Gay-Straight Alliance my first year. It shows up in a tiny corner of Sophomore year and by the next year there I am, co-chairing it. I have vague memories that someone else founded it right before leaving Garfield, I try to find journal entries about it—when did I realize it was there, who told me, or even knew I’d be interested—but get stuck in all the heartbroken mud of young gay me and can’t bare to look at any more teenage longing, abandon the journals. Adult me notes wryly that someone on yearbook staff helpfully titled our page ‘Coming Together.’ The caption under our smiling co-chair photo, proudly holding the new Safe Staff List, says the group formed in 1998; the earlier yearbook says the GSA started as the result of an idea formulated by Seniors Dana Prince and Clyde Petersen.

36. A million possibilities

The pandemic is still sinking its teeth in but a miracle has happened—my mom found my old preschool teacher on social media, put us in touch, we’re now on a video call. “But you should really talk to Mardie,” she says, “they were best friends, even though they were divorced.” It turns out Rob’s ex-wife Mardie Rhodes used to work with my dad, they are old friends even. A million possibilities open inside me like a nervy rainbow of butterflies. Mardie is excited to meet me. After all these years, he’s been right here. As she talks about their life, warmly throwing up her hands or laughing heartily at dark moments, more and more names overlap—her old friend Paul Feldman in the AIDS Memorial Pathway committee I’ve attended, apparently he knew Rob too, my parents’ friend Mark Secord pushing Virginia Mason to agree to run Bailey-Boushay, and Rob dying there of course, I imagine him rushing into the art of my field trip, apparently he died in 1995. I don’t know if the newly revealed web of mashed-up connections means this world is small or huge. Maybe it just means I’m old now, and living where I grew up.

37. First symptoms

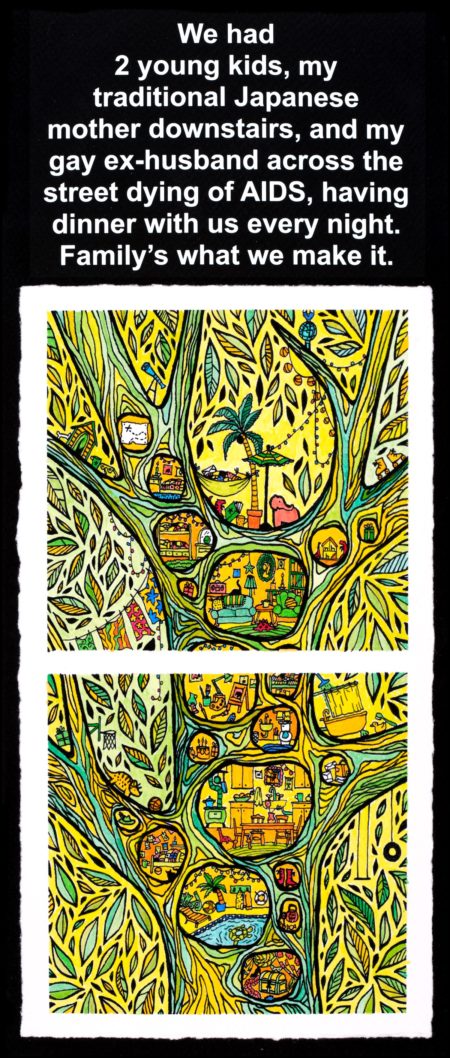

Mardie emails me about Rob to help me with ideas for my Cal Anderson public art. “Sometimes there are scenes, like old time slide shows in my head. Our first trip out west, hiking in a field of wildflowers in Wyoming. Our old army pup tent that we used for camping on our first trip. Seeing the Rocky Mountains for the first time. We loved animals. Rob got me my first dog and our first cats. We adopted our cats before we came out west, so they traveled from Pennsylvania to Washington with us.” They met in college, got married, moved here together. Both trained as teachers, he did all kinds of art and drama but she ended up in PR. She tells me his dad was abusive, that Seattle was the first time he realized “you could be gay without it causing you bodily harm.” A private inward wince. Rob coming out was messy and painful—she does not sugarcoat their divorce—but still, they rebuilt. She remarried and had kids and still, Rob stayed in the family, nannying her son, living across the street, cheekily rearranging her living room decor as he cleaned up from spontaneous art sessions there while she was at work. “The most annoying part,” she laughs, “is that he always made it look better.” She adds in the email, “Big memories around Ravenna Park, we lived near the pedestrian bridge and we’d go on daily walks through the park with the kids, with the dog, with Rob. In fact, we were walking through Ravenna Park when he first told me he was having AIDS symptoms.”

38. Effort was needed

I reach out via social media to ask Clyde and Dana about the Garfield Gay-Straight Alliance. Dana is now in Ohio, a professor of social work focusing on changing systems like child welfare and juvenile justice to radically support LGBTQ+ youth. Clyde is a prolific multidisciplinary artist, making films, music, installations, and now even founding an artist residency. I’ve never talked with either on the phone till now, the last time I ran into Clyde was in that Public Art Bootcamp. He politely asks how the art is going, they’re both so nice to talk to, he mentions a Garfield Messenger article about the GSA’s formation. I’ve forgotten all about it but Clyde thinks he has a copy on his zine shelf, laughs gently that his memory here is sharper because “accidentally” leaving this article on the kitchen table was how he came out to his dad. He immediately sends a scanned copy, I wonder now if that’s how 10th-grade me first knew about the group. They both mention transitioning from a support group called People for People, run out of a counselor’s closet-sized office—Dana laughingly describes her teenage self as roaring to literally GET OUT OF THAT CLOSET. The confidential meetings were vulnerable to the whims of other students, each time the door opened it could equally be a new attendee or random kids yelling “faggots!” Clyde thinks the change was spurred by one particular student getting beat up and dropping out, a sense that a more openly activist effort was needed to make the school safer. He reminds me of organizations I’d long since forgotten, about making a Queer Youth Rights zine under the umbrella of the Seattle Young People’s Project. Dana remembers wishing the new group could be a queer-only space, but being convinced by others that the “Straight” in the name was necessary cover for students who couldn’t come out yet. This was all happening their Senior year, they were in Running Start and barely around school other than getting paperwork together to formally start this group. And then they graduated. None of us remember how a basically unknown Sophomore and a crushingly shy Freshman ended up in charge of bringing the GSA into the next school year. Dana’s probably right: “I think there was a void, no one wanted to do it and we were all leaving. Someone told me you were willing.”

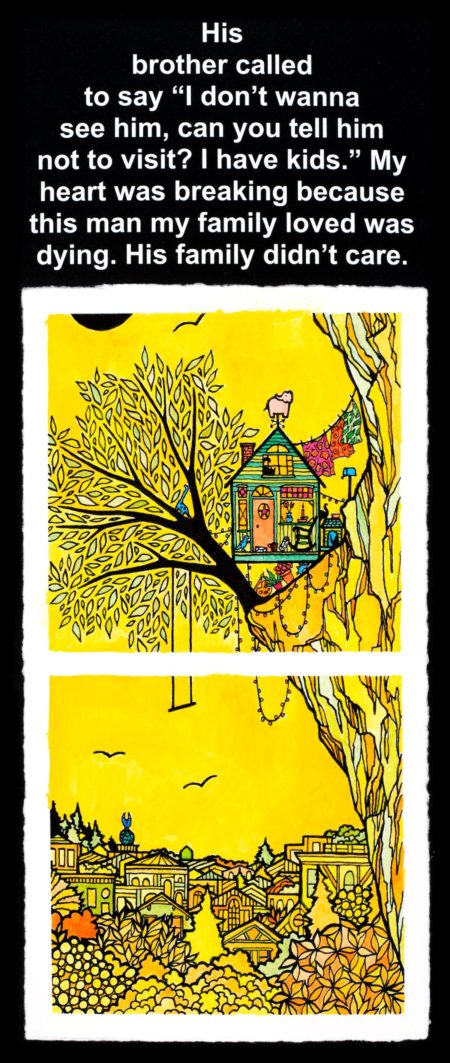

39. One horror

Shortly after a joyful solo trip to Hawaii, Rob developed AIDS-related dementia. This is one horror of AIDS I’d never heard about. Mardie processes it later in some private writing, strained and pushed passed the limit. She had to commit him to Harborview. Eventually he comes back from it, but so many things are destroyed. He loses his apartment, but that’s not the point of what she’s telling me. “He trashed his apartment, but in the process of doing that he was also an artist. So when we went to clean it up there were little altars everywhere, of different creations.” Her quick smiles disappear when she talks about the younger brother who didn’t want Rob to visit him and his kids. “I lost it. I said to him, he’s been sick and one of the things he has in his apartment is a little altar and it’s got fresh flowers and candles on it and a photo of you as a toddler and his arm is around you. That photo is in a place of honor in his apartment. I want you to keep that thought after he’s dead.”

40. Seattle Gay Clinic

I don’t know how my neighborhood video store comes up, but Mardie offers quickly “Yes, that’s where the clinic was.” Before On 15th Video moved in, I realize Fire Station No. 7 housed Country Doctor, where the all-volunteer-run Seattle Gay Clinic happened on Wednesdays and Saturdays, starting in 1979. In an online video, Tim Burak describes meeting one night in the fireplace room of “the old firehouse,” organizing what became the NW AIDS Foundation. I imagine Rob waiting for tests while little kid me gazes on narrow aisles of poofy-dressed musicals in the original location across the street.

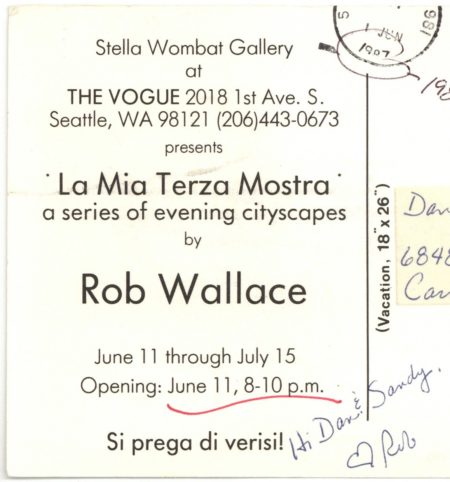

41. Kid explorers

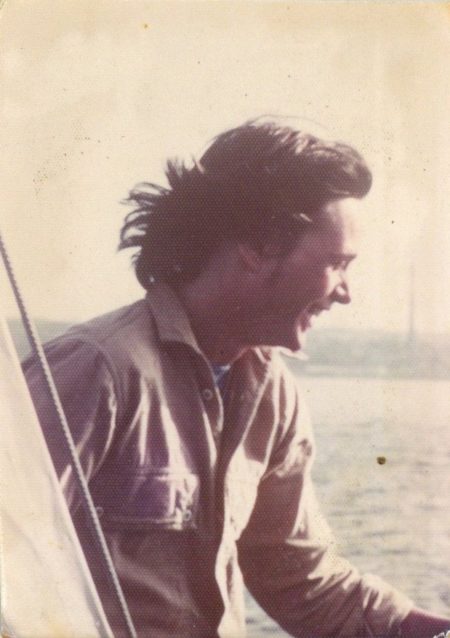

Mardie shares more memories for my public art plans, my drawings increasingly stuffed with detail. Plans to make a children’s book together, shared love of kid explorers, Rob loving the sun, the center of attention in any room, his art show at the Vogue cleverly-titled 3D paintings with the Pink Elephant Carwash sign and the P-I Globe, Halloween costumes and dress-up, there’s just one photo in drag, she’s right, the small polaroid is stunning. In the album it’s next to one of Rob and my preschool teacher relaxing on bright sunny stairs. Mardie’s husband and Rob shared a love of MTV, when it was new they’d hide out in the basement wasting hours watching. Mardie describes arriving home from work, demanding what had kept them from helping out with chores or dinner and the two of them yelling up, wickedly gleeful: “We’re just writing in our journals!” When I finally visit in person, sitting 6 feet apart on her foresty back deck, she nods happily to a big pine tree. “We sprinkled some of him there, and then some of him in the southwest corner of the yard, because he really loves sunshine.”

42. Remind me again

The Boushay Solarium is both made of art and full of art. In the emailed photos, the walls look like my friend’s living room during the years it turned a dark secretive blue so deep it looked literally deep, made of hidden depths, but a blue that is also inexplicably somehow yellow and orange, warm. Mary Ann explains the color was intentionally between warm and cool, for AIDS patients struggling to control their body temperature. A long polished branch railing corresponds to the life cycle of a tree, and the column has slits for leaving notes in it if people wanted to. My face crumples up involuntarily. She’s sent me photos of the notes for Frank Boushay buried under the floor, they’re all addressed “Frankie.” She also shares that William Stafford’s poem ‘The Story’ was embossed to make it easier for hard-of-seeing patients to read. I think the poem panel looks just taller than a body. In the photo I see only parts, coppery letters emerging in snippets from the blue—

REMIND ME AGAIN – TOGETHER

STRANGE JOURNEY

OTHER COME ON LAUGH

SOME TIME WE’LL CROSS

BOTH

FOREVER

I’LL TOUCH YOU

There are other pieces along the wall above the branch. Last in the email, a photo of a painting called ’29 Pebbles’—Frank Boushay lived 29 years. His family said the finished room was “perfect, a cross between a chapel and a disco.” This statement is hugely, unnervingly familiar to me, I must have asked her about this before.

43. It was a magical place at that point

Toward the end, after the dementia, Rob spent his days at Bailey-Boushay House in what Mardie fondly refers to as an adult daycare type thing. Befriending lots of drag queens, designing Erte-themed costumes, “I don’t know how all that happened, but this drag queen Halloween thing was happening at Bailey-Boushay and Rob was in the middle of it, and then my kids and I were visiting, and what they remember is that there were a lot of cool people who like to dress in costumes, and that the juice bar there, you could mix apple juice and orange juice and some other juice together.” She throws her hands up and laughs. “And that’s what they remember.” Her face turns serious. “It was a magical place at that point. They did a good job, they really did.” We never talk about the real end, even though I know now he died there. “There was something about that place, where people came together to just care for people dying of AIDS, where you could be authentically yourself and just, you know, lose it. Because you’re holding it together for everybody else around. Because so many people were dying.”

44. On 15th Video

Six months after I move into my post-divorce apartment nearby, the video store closes. The last movie I rent feels so much like my high school self—on the edge of queerness but not, arty and poised for something epic but also not, nothing much happening, up late at night alone, starring Tilda Swinton. I dutifully drop it through the return slot rather than keeping it as a souvenir. Nowadays the historic fire station is an expensive gift shop, I walk in once for the memories, missing the springy hop up the stairs and into warm orangey light. It doesn’t really work anymore, something less friendly. But peeking around the corner, behind the empty QFC I still see ghosts of teenage me—swiftly clomping through the rainy-dusked alley in my overloved clogs, happy jolts of lonely fresh air in my face, whatever music in my headphones turning every sad back fence into poetry, blithely dodging potholed puddles like some grungy ballerina.

45. Before they moved here

Working on the art for the park windows, young Mardie and Rob keep getting stuck in my chest. I’m drawing other things but my heart keeps uncomfortably snapping back to before HIV/AIDS had a name or existed even, before they moved here, before Rob realized that being in love with Mardie didn’t mean he was straight. My emotions seem to be rushing away without me, looking for the warmth of some rickety precious moment before any danger was clear. “Our first apartment together was in the top floor of an old victorian house in Meadville, PA,” Mardie writes. “We had a gazillion steps to our apartment, but the old-style sunroom, right out of Mary Poppins, was only accessible from our bathroom. I had the room filled with houseplants. We loved that dang sunroom. Rob used to climb out onto the roof to read the paper and sunbathe on sunny days.”

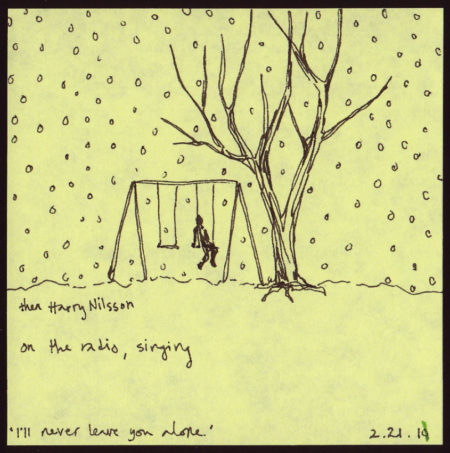

46. On the radio

I know how the world is, we are not the majority, even if elementary school me hopefully listening to Judy’s lesbian lovesong in the car did beat the odds and get to grow up gay. The world is big and I’m used to being fond of things that aren’t fond of me, it’s ok. I’ve assumed my early teen years were soundtracked by the straight world’s song picks and by Senior year the radio is changing anyway, DJs are gone, I move from 107.7 to 90.3 and more or less stay there for life. But his voice comes on one sudden Sunday afternoon in middle age, I’m working tiredly on a laptop, years after divorce and another country and coasts and back in with my parents I’m so grateful and now here, my own place, working every day. DJ Marco Collins is filling in on 90.3, he sounds exactly the same, a delight and sweeping time travel, old friendships and lonely homework, awkward outfits long hair I’ll never have again, laughing with girls I loved in confusing ways, or people I ended up loving forever. I realize finally that he is gay. Openly so. What magical relief, to have any piece of my history come from my people.

47. Separate death

Mardie graciously loans me her family photo album of Rob. Towards the end of 2021 it’s still sitting near me at the studio, comfortably piled alongside recent drawings and painted prints and research materials from all the public art projects I’ve done during the pandemic. Rob’s obituaries are carefully pasted on two separate sides of the last page, back-to-back like two sides of a coin. There’s the Seattle one, full of art projects and teaching and theater and costumes and play, a world of community anchoring Rob’s warmly calm smile in the photo above. Remembrances are directed to Bailey-Boushay House and the Chicken Soup Brigade. The Pennsylvania one says he “died in his home of lung cancer” and lists onetime jobs like water ski instructor, archives clerk, an Alaskan crab boat—even his former church membership—before adding “he also painted portraits.” They even list separate death dates, one day apart.

48. Temporary

My temporary AIDS Memorial Pathway public art goes up just in time for the dedication ceremony for the nearby permanent artworks. It feels glorious and strange and like I know everyone in Cal Anderson Park, or everyone is a friend waiting to happen. Within days the art is immediately defaced, repeatedly defaced all summer and fall, pieces slashed and picked apart eventually replaced. Straight white friends all talk about the thoughtless stupidity, LGBTQ+ and BIPOC friends mostly feel the defacement as personal, specifically homophobic, hateful. Everyone is deeply kind, and both things can be true. Waiting for the replacements, some anonymous stranger tries to put one back together like a puzzle. Their gentle effort sweeps me off my feet.

49. Undeniably limited

I’m aware the phrase Gay-Straight Alliance is outdated and binary, undeniably limited in what it encompasses. Many of us were transgender, many students didn’t come, came out later, probably didn’t feel safe there, we all have different memories anyway, intersecting and overlapping and diverging. Even back then, the group was only one piece of one school’s LGBTQ+ community, only worked for some of us, always partial and imperfect. My story is just my story. But it unnerves me how hard it is to uncover just my own immediate history—personally, for myself—let alone larger community histories. How disappointingly invisible, even from a time as recent as the late-90s, even now, how unsearchable our individual and collective stories are. How does a queer or trans student at Garfield today ever know how many of our memories are hanging around there, silently rooting for them.

50. Here in the future

In all our talks, Mardie is unfailingly funny and sharp, generously open, memories and laughs and thrown up hands cascading across the phone or computer screen. When I arrive at her backyard in summer 2020, she’s waiting for me—with the entire 5th grade history lesson out on her deck, shockingly here in the future, famous paintings leaning carefully against the house just for me. Rob made them as a student in a painting class at Seattle Central. I can’t believe it—she actually gives me the van Gogh, real as ever, a daily companion now. At one point Mardie pauses to detail the timeline: “In 1990 he got tested, I remember because I was pregnant. He knocked at the door of my office and he had this big”—she’s smiling—“gave me a big hug and he kissed me. And it was the first time he kissed me, probably in years and years and years because he had just gotten the results that he was negative. So in ’90 he was negative and ’92 he was positive and in ’95 he was dead. So fast.” Her voice drops to a lower register, quieter. I ask how old was he. “42? 43? God that seems like such a child now.”

51. Pablo

This writing is so long, and there’s also a million things I can’t say. The landscape of the neighborhood, even my childhood playground in Volunteer Park, teeming with private memorials I don’t have permission to name, countless histories bigger than mine, people I don’t know. I apologize for everything that’s missing. I know so many people know more than me. You can tell me things, or ask me questions, I promise.

52. My journal

Rob died in late November 1995. I’m in 8th grade then. By 9th grade I’m writing furiously or forlornly in my journal every night, my handwriting just a touch younger than adulthood, a little baby-fat clinging around the j’s and I’s. The entry exactly a year after his death is when everything shifts, from here in the future I can tell what’s happening even if I can’t quite find when I came out. But in 8th grade there’s nothing written for months at a time, I don’t know what I was doing when Rob died. I’m almost as old as he ever got when it occurs to me to look further back: 3/28/95, 7th grade. Apparently Adam Ant and Bjork and Green Day and Nine Inch Nails and Elastica are on the radio, I’m excited for my first show at the Mercer Arena, fiercely loyal friends and vague crushes and wanting a swimsuit. Suddenly there it is. “Rob Wallace is dying (or dead) of AIDS. I didn’t know he had it. I’m making a tape ‘for him’.” I did know his last name after all.

53. Rob

The only time I can actually hear Rob speak now is an old letter to Mardie. This is early after their divorce, distance starting to heal their friendship, Rob’s working on the crab boat in Alaska. He’s younger, so much younger than I am now. Dear Mardie, Hi little pookie nookie twokie dookie mollymanookie. Well I’m still here. Dutch Harbor is slowly revealing its charms to me. Just because this has been the longest week of my life doesn’t mean that I’m not having a ball: This is where it is at. I was really pissed last night. The grocery store across the street closed at 7 instead of 9. I didn’t really need anything. But one of the things to do here is to hang out in the grocery store. Just hang out. I walked to Unalaska the other day, again. Then I came home. Unalaska is a lot like the grocery store that way. I’ve made all the art and written pages and pages and there’s still absolutely nothing to be done with this emotion—I feel so excited to meet him.

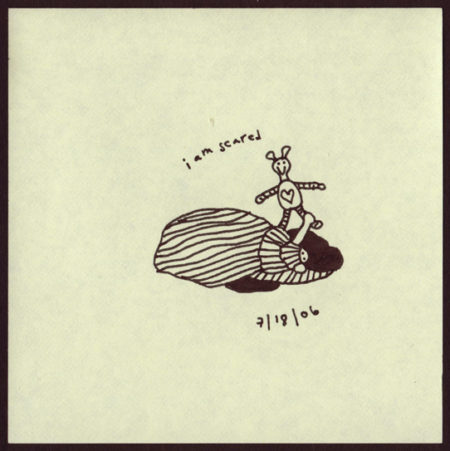

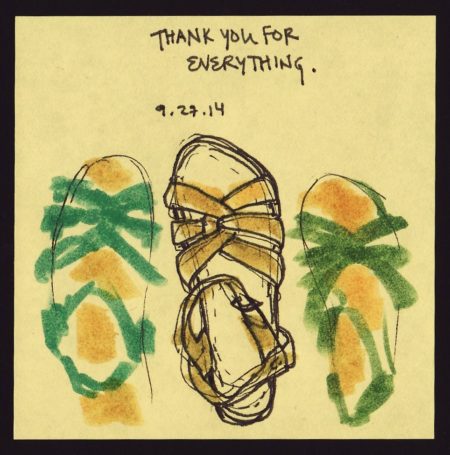

Clare Johnson is a dyke-identified writer and artist. For 13+ years she’s drawn and written on a post-it every night to hold onto something from each ending day, making almost 5,000 pieces so far, which have been excerpted in the Seattle Review of Books lyric essay column. Her window art in Cal Anderson Park for the AIDS Memorial Pathway (based on interviews with long term survivors about HIV and family) and her art banners at N 35th St & Interlake Ave N (inspired by local seniors’ memories around water) are both on view until August 2022. She’s currently completing her hybrid form manuscript, Will I live here when I grow up, mixing current life with themes of historical westward migration and family stories. Her writing also works to unearth queer histories, without pretending that those voices weren’t forcibly erased.